You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Tarot History & Research’ category.

While there certainly have been plenty of prohibitions historically against playing cards, usually the focus was anti-gambling. There have also been laws allowing card playing, especially during certain times of the week or year and sometimes even allowing penny bets. Right from the beginning there have been those who saw cards as a popular artifact that could be used as much for moral purposes as immoral. The point that I want to make in this series of posts is that people have seen playing cards in terms of allegories that point them toward the best (or worst) ways in which to live their lives. There is something about these loose leaves that through shuffling allow ‘fate’ to herald triumph or loss that has always appealed both to the imagination and to our belief that we can be guided to a morality that will result in triumph.

Those who have seen the Showtime production “The Tudors” might recognize the name Hugh Latimer. He was one of the foremost Reformation preachers in the courts of Henry VIII and Edward VI.

Those who have seen the Showtime production “The Tudors” might recognize the name Hugh Latimer. He was one of the foremost Reformation preachers in the courts of Henry VIII and Edward VI.

Hugh Latimer (c. 1490-1555) was said to have done more than anyone else to establish the principles of the English Reformation in the minds and hearts of the British people. His homely simplicity of style, practicality and humor made the zeal and wisdom of his sermons palatable to the masses. These sermons are still read today as a model of the craft.

When his two “sermons on the cards” resulted in a major controversy at Cambridge, Henry VIII came to his support, returning the favor of Latimer’s support for the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon. As court chaplain and an ardent promoter of reform, Latimer earned a brief excommunication by the pope. With the creation of the Church of England, he was named Bishop of Worcester although his path continued to have its ups and downs. Eventually he became chaplain to Catherine, Duchess of Suffolk, who was Catherine Parr’s close friend and, it was rumored, was being considered as Henry’s seventh wife. Under Edward VI, Latimer was court preacher, but upon the ascendancy of Queen Mary and the return of Catholicism, he was burned at the stake, becoming known as one of the Three Oxford Martyrs. Latimer appears as the chaplain of Catherine Parr in the recent TV series “The Tudors.”

The statutes of St. John’s College, Cambridge, following the usual practices of the time, forbade playing with dice or cards except at Christmas (excluding underclassmen). As this popular activity would obviously draw the holiday interest of university students, Hugh Latimer used the metaphor of ‘Christ’s cards’ in a game of Triumph for his Christmas sermons in 1529.

Trump or triumph was a 16th century British card-game, using a regular playing-card deck, based on earlier trick-taking games such the German Karnöffel. Their descendants include whist, hearts and bridge. Karnöffel was first described in Bavaria in 1426, and its name may have derived from the Persian Kanjifah and Indian Ganjifa, which speaks for the historical movement of playing cards from East to West (see discussion here). Karnöffel may even have been a precursor to the tarot in that certain cards, when played in particular ways, were given names: the Seven of Trump became the Devil when it was the first card played in a trick, the Six was the Pope and Two, the Kaiser.

In Triumph, twelve cards were dealt to each of four players with four cards left in a stock pile (sometimes called the ‘widow’). The top card of the stock was turned up for trumps.

SERMONS ON THE CARD AND OTHER DISCOURSES

by Hugh Latimer

The Tenor and Effect of Certain Sermons Made by Master Latimer in Cambridge, About the Year of Our Lord 1529

December, 1529, the Sunday before Christmas

The first sermon begins with the question “Who Art Thou?”* and Latimer answers that we are natural [beastial] man and woman, and therefore ‘the true inheritors of hell and working all towards hell,’ that is, until we are baptized and given ‘Christ’s rule.’ Latimer’s two sermons explain the key tenets of ‘Christ’s rule’ as viewed through an analogy with a card game in which all who follow this rule can win. [*The question “Who Art Thou?” reminds me of the Oracle of Delphi, who counseled “Know Thyself.” -mkg]

We’ll pick up in the middle of the first sermon:

“Now then, what is Christ’s rule? . . . And because I cannot declare Christ’s rule unto you at one time, as it ought to be done, I will apply myself according to your custom at this time of Christmas: I will, as I said, declare unto you Christ’s rule, but that shall be in Christ’s cards. And whereas you are wont to celebrate Christmas in playing at cards, I intend, by God’s grace, to deal unto you Christ’s cards, wherein you shall perceive Christ’s rule. The game that we will play at shall be called the triumph, which, if it be well played at, he that dealeth shall win; the players shall likewise win; and the standers and lookers upon shall do the same; insomuch that there is no man that is willing to play at this triumph with these cards, but they shall be all winners, and no losers.

Here Latimer makes the point that as opposed to ordinary card games where there is one winner, everyone who follows Christ’s rule wins.

“Let therefore every christian man and woman play at these cards, that they may have and obtain the triumph: you must mark also that the triumph must apply to fetch home unto him all the other cards, whatsoever suit they be of. Now then, take ye this first card, which must appear and be shewed unto you as followeth: you have heard what was spoken to men of the old law, “Thou shalt not kill; whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of judgment: but I say unto you” of the new law, saith Christ, “that whosoever is angry with his neighbour, shall be in danger of judgment; and whosoever shall say unto his neighbour, ‘Raca,’ that is to say, brainless,” or any other like word of rebuking, “shall be in danger of council; and whosoever shall say unto his neighbour, ‘Fool,’ shall be in danger of hell-fire.” This card was made and spoken by Christ, as appeareth in the fifth chapter of St. Matthew.

“Let therefore every christian man and woman play at these cards, that they may have and obtain the triumph: you must mark also that the triumph must apply to fetch home unto him all the other cards, whatsoever suit they be of. Now then, take ye this first card, which must appear and be shewed unto you as followeth: you have heard what was spoken to men of the old law, “Thou shalt not kill; whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of judgment: but I say unto you” of the new law, saith Christ, “that whosoever is angry with his neighbour, shall be in danger of judgment; and whosoever shall say unto his neighbour, ‘Raca,’ that is to say, brainless,” or any other like word of rebuking, “shall be in danger of council; and whosoever shall say unto his neighbour, ‘Fool,’ shall be in danger of hell-fire.” This card was made and spoken by Christ, as appeareth in the fifth chapter of St. Matthew.

“Now it must be noted, that whosoever shall play with this card, must first, before they play with it, know the strength and virtue of the same.

Latimer thus explains that the first card drawn determines trump and that this winning trump is the commandment “Thou shalt not kill.” Furthermore, that under the ‘new law’ of Christ, this extends to ‘killing’ a person with damaging feelings and words. When he continues, he characterizes such evil actions within us as ‘Turks,’ which can make us slaves. [If the word, Turks, used in this way, offends you, think of the intent as being evil genii or germs that affect our morals. See note at the end.]

“These evil-disposed affections and sensualities in us are always contrary to the rule of our salvation. What shall we do now or imagine to thrust down these Turks and to subdue them? It is a great ignominy and shame for a christian man to be bond and subject unto a Turk: nay, it shall not be so; we will first cast a trump in their way, and play with them at cards, who shall have the better. Let us play therefore on this fashion with this card. Whensoever it shall happen the foul passions and Turks to rise in our stomachs against our brother or neighbour, . . . we must say to ourselves, “What requireth Christ of a christian man?” Now turn up your trump, your heart (hearts is trump, as I said before), and cast your trump, your heart, on this card; and upon this card you shall learn what Christ requireth of a christian man—not to be angry, nor moved to ire against his neighbour, in mind, countenance, nor other ways, by word or deed. Then take up this card with your heart, and lay them together: that done, you have won the game of the Turk, whereby you have defaced and overcome him by true and lawful play. . . .

“Then, I say, you should understand, and know how you ought to play at this card, “Thou shalt not kill,” without any interruption of your deadly enemies the Turks; and so triumph at the last, by winning everlasting life in glory. Amen.

The Second Sermon

“Now you have heard what is meant by this first card, and how you ought to play with it, I purpose again to deal unto you another card, almost of the same suit; for they be of so nigh affinity, that one cannot be well played without the other. The first card declared, that you should not kill, which might be done divers ways; as being angry with your neighbour, in mind, in countenance, in word, or deed: it declared also, how you should subdue the passions of ire, and so clear evermore yourselves from them. And whereas this first card doth kill in you these stubborn Turks of ire; this second card will not only they should be mortified in you, but that you yourselves shall cause them to be likewise mortified in your neighbour, if that your said neighbour hath been through your occasion moved unto ire, either in countenance, word, or deed. Now let us hear therefore the tenor of this card [essentially, he speaks of reconciling with thy neighbor]. . . .

“The first card telleth thee, thou shalt not kill, thou shalt not be angry, thou shalt not be out of patience. This done, thou shalt look if there be any more cards to take up; and if thou look well, thou shalt see another card of the same suit, wherein thou shalt know that thou art bound to reconcile thy neighbour. Then cast thy trump upon them both, and gather them all three together, and do according to the virtue of thy cards; and surely thou shalt not lose.”

Johannes de Friburgo, 1377

Johannes de Friburgo, 1377

The moralization of the Game of Cards did not begin with Latimer but with Johannes de Friburgo (also known as Johannes von Rheinfelden) in 1377, Basil, Switzerland. This work is one of the earliest mentions of playing cards in Europe and is known as: De Moribus et Disciplina Humane Conversationis, id est ludus cartularum “Of the Manners and the Instruction of Humane Conversation, that is the game of cards” (described by E. A. Bond in The Anthenaeum, Jan, 19, 1878).

Johannes proposed to “moralize the game, or teach noblemen the rule of life; and to instruct the people themselves or inform them of the way of labouring virtuously.” In other words, the game of cards, according to Johannes, can be used for teaching manners and humane conversation. He further writes: “Hence it is that a certain game, called the game of cards [ludus cartarum], has come to us. . . . In which game the state of the world as it now is is excellently described and figured.”

[See the discussions of this work by Michael J. Hurst and also at trionfi.com. The image is from Roman du Roy Meliadus de Leonnoys, c. 1352 (Naples).]

Martin Luther, 1525

Martin Luther, who elsewhere spoke against gambling, declared himself to be God’s Ace who trumps the pope. Bells are a German suit-marker. He gives cards identities similar to those in Karnöffel in this quote from 1525, four years before Latimer’s sermon:

Martin Luther, who elsewhere spoke against gambling, declared himself to be God’s Ace who trumps the pope. Bells are a German suit-marker. He gives cards identities similar to those in Karnöffel in this quote from 1525, four years before Latimer’s sermon:

“If I were rich, I would have myself made a golden chess set and silver playing cards as a remembrance; for God’s chesspieces and cards are great and mighty princes, kings, and emperors; for He always trumps or overcomes one through another, that is lifts him off his feet and throws him down. N. [Ferdinand] is the four of bells, the pope the six of bells, the Turk [Devil] the eight of bells, and the Emperor is the king in the pack. Lastly, our Lord God comes, deals out the cards, and beats the pope with the Luther, which is His ace [Daus].”

[Tischreden 1:491-2, no 972, quoted in “Playing Cards and Popular Culture in Sixteenth-Century Nuremberg” by Laura A. Smoller, in The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 17, no. 2, (Summer, 1986).]

NOTE on the word “Turk”: Both Hugh Latimer in England and Martin Luther in Germany used the word “Turk” as roughly synonymous to the Devil. Today this is, of course, not considered politically correct. In the 16th century the Turks were the boogey-men that all children were taught to fear. Constantinople had fallen to the Muslim Ottoman Turks in 1453, ending the Christian Byzantine Empire. Even more recently they had temporarily captured a part of Italy, and then, in 1529, after several earlier forays, the Turks sailed up the Danube and besieged Vienna. Although they were driven out, Europeans lived for a couple of hundred years with anxiety about an impeding invasion by the Turks. A helpful summary of the Ottoman Empire and its rapid spread can be found here.

Continue on to

Here’s an hd four minute extension of my original animoto video from The Cartomancer Series. Try it full screen. What do these images say about cartomancers and cartomancy?

Not everyone knows that tarot appears to have originally been created as a trick-taking game related to whist or bridge. It is still played today on the European continent, where it is called Le Tarot in France, Tarocchi in Italy and Tarock (or some variation of that) in Eastern Europe. Most people play with a specially designed double-headed deck with French suit markers and completely different trump illustrations featuring large numbers on them, as these decks are more conducive to game-playing (see here and here). You can learn more about the game at Tarocchino.com, which is the source of the following excellent video on the history of tarot and gaming. See also John McLeod’s website on Card Games, especially Tarot Games. You can download a reasonably priced shareware computer version of this game (with free trial period) in English or French for both Mac and PC at LeTarot.net. I’ve posted simplified instructions for playing the game here.

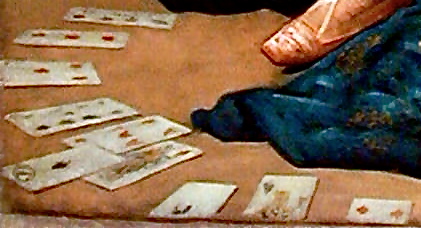

No one knows the story behind the painting “The Fortune-Teller” by Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), so it is ripe for speculation. It was painted in 1508 when Lucas was only fourteen, marking him as one of the great painters of the age. This work is also considered to be the first “genre painting” that depicts everyday events in ordinary life. If what is shown is truly fortune-telling with cards then it is one of the earliest records of cards being used in this way (see Origins of Playing Card Divination).

I believe the cards in this picture represent the many turns of fortune, but it may be more of a metaphor than an actual card reading. Still, we know from research by Ross Caldwell that by 1450 playing cards were used in Spain for fortune-telling “puédense echar suertes en ellos á quién más ama cada uno, e á quién quiere más et por otras muchas et diversas maneras (“one can cast lots [tell fortunes] with them to know who each one loves most and who is most desired and by many other and diverse ways.”) And, as we will see, both of the main characters in the painting married into the Spanish royal family and spent time there.

The central woman is thought by some to be Margarethe (Margaret) of Austria and Savoy (1480-1530) (see also here). Born in Flanders, she was daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I and Mary, Duchess of Burgundy. Her step-mother was Bianca Maria Sforza, daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, by his second wife, Bona of Savoy, and granddaughter of Bianca Maria Visconti (m. Francesco Sforza) for whom the Visconti-Sforza Tarot was made.

At three years of age Margarethe was betrothed to the Dauphin of France (later, Charles VIII), but at ten was returned to her family when he married someone else. In 1497, at seventeen, she and her brother, Philip ‘the Handsome’ (Archduke of Austria, ruler of Burgundy and the Netherlands, and in line to become Holy Roman Emperor), were married off in a double alliance to the Infante Juan and Infanta Juana, children of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile (who sent Columbus to America). (Pictures below are of Philip and Margarethe.)

The Infante Juan died six months later and Margarethe’s child was stillborn. Margarethe was then married to Philibert (Phillip) of Savoy with whom she was very happy, but he died three years later. (He, by the way, actively supported the Milanese cause of the Sforzas against the French until offered a bribe by the French that he couldn’t refuse.) So, by the age of twenty-four she had already had a betrothal broken by France’s Charles VIII, lost a child, and was the widow of both the Infante Juan of Spain as well as of her much loved Philibert. Although her family tried to entice her into a marriage with Henry VII of England, she vowed never to remarry and took the motto: FORTUNE . INFORTUNE . FORT.UNE that has been translated as “Fortune, misfortune, and one strong to meet them.” I see it as both a reminder of her sad story and her claiming of the strength (forte) that such adversity had brought her.

Meanwhile, in 1506, Margarethe’s beloved brother, Philip the Handsome, was named King of Spain, but he died that same year, his son becoming the next King of Spain (Carlos I) and eventually Holy Roman Emperor (Charles V). In 1507 Margarethe was named governor of the Habsburg Netherlands, in place of her brother, and guardian of his seven-year-old son. She went on to become a significant political figure and patron of the arts, negotiating treaties and continuing to rule the Netherlands at the behest of her father, Maximilian, and then her nephew.

There is a possibility that Lucas van Leyden’s 1508 painting commemorates Margarethe of Austria’s ascendancy to the governorship of the Netherlands in 1507, following the death of her brother, Philip the Handsome. The flower being exchanged (a “pink” signifying loyalty in love?) could represent the passing on of the governorship and their love for the people of the Netherlands who could be the commoners pictured in the background witnessing the change-over. The daisy on the woman’s gown could be meant to identify her (a marguerite daisy). Philip the Handsome (portrait above left) wears a necklace and hat similar to those in “The Fortune Teller” where his doffed hat and sad eyes seem to illustrate his mortal leave-taking. The portrait on the right shows Margarethe in widow’s garb as she liked to be seen in the second half of her life. The Fool with his bauble (fool’s sceptre) may have been someone specific at the court or he may be a symbolic reminder of the foolishness of thinking that a high place and worldly honors will last. More people look at him than at anyone else. There are clearly three layers to the cards: Philip & Margarethe, the Fool and a lady-in-waiting(?), and a backdrop of commoners who may represent the people of the country who are unsure what is to become of them.

At least one other painting by van Leyden is said to show Margarethe’s involvement in political negotiations pictured as a card game (1525; see below). It is thought to refer to a agreement between Emperor Charles V (left) and Cardinal Wolsey (right) to form a secret alliance between Spain and England against Francis I of France. Margarethe is known to have been involved in these negotiations. This painting would therefore refer back to the 1508 one where her position as regent of the Netherlands was commemorated.

A nineteenth century etching based on the painting (the etching is from Le Magasin pittoresque, 1840) was identified as “The Archduke of Austria Consulting a Fortune-Teller” when reproduced in Chambers‘ article on card reading. It has often been depicted as proof of early playing card divination. As we’ve seen, that may be too simplistic a view. However it is interesting that Philip the Handsome was Archduke of Austria (and his sister became Archduchess of Austria after him).

Here’s a couple more portraits of Margarethe. The one on the right has a similar neckline to the one in our painting (though slightly higher):

Here’s a couple more portraits of Margarethe. The one on the right has a similar neckline to the one in our painting (though slightly higher):

.

.

.

.

[Special thanks to Huck Meyer, Rosanne, and Alexandra Nagel—all who offered pieces of the puzzle.]

Gertrude Moakley (The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo, 1966) introduced the Tarot world to a possible original source of the Papess card: Maifreda (or Manfreda) Visconti da Pirovano was to be declared Pope in Milan on Easter 1300 in a new age of the Holy Spirit. Instead, Maifreda and others in the sect were, that year, burned at the stake, along with the disinterred body of Guglielma, who had inspired this new movement. Could Maifreda be depicted on the Tarot Popess card?

Gertrude Moakley (The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo, 1966) introduced the Tarot world to a possible original source of the Papess card: Maifreda (or Manfreda) Visconti da Pirovano was to be declared Pope in Milan on Easter 1300 in a new age of the Holy Spirit. Instead, Maifreda and others in the sect were, that year, burned at the stake, along with the disinterred body of Guglielma, who had inspired this new movement. Could Maifreda be depicted on the Tarot Popess card?

Maifreda was an Abbess in the Umiliati Order and first cousin to Matteo Visconti, the Ghibelline (anti-pope) ruler of Milan. Maifreda believed the Holy Spirit had manifested on earth in the form of Guglielma (d. 1281), a middle-aged woman with a grown son who claimed to be a daughter of Premysl Otakar,King of Bohemia, and, who on arriving in Milan in 1260, donned a “simple brown habit” and lived the life of a saint. To the Guglielmites, her arrival fulfilled a prophecy of St. Joachim de Fiore that a new age of the Holy Spirit would begin in 1260, “heralding the inauguration of an ecclesia spiritualis in which grace, spiritual knowledge and contemplative gifts would be diffused to all.” Although she vehemently denied it, “rumors of divinity already swirled around Guglielma during her lifetime.” And, “Her words about ‘the body of the Holy Spirit,’ together with her mysterious royal origins, Pentecostal birth, imputed healings and stigmata, coalesced to create a more-than-human mystique in the minds of her friends.” Immediately after her death dozens of portraits were painted and chapels were dedicated to Santa Guglielma. (Visconti-Sforza card on the right – her cross at top left is hard to see.)

Barbara Newman (aka Mona Alice Jean Newman) presented the most complete account in English of the Guglielmites in her From Virile Woman to WomanChrist: Studies in Medieval Religion and Literature, but it is in her more recent paper, “The Heretic Saint: Guglielma of Bohemia, Milan and Brunate,” that we learn important details that make an attribution to Maifreda as Papess much stronger than previously thought (all quotes and information not otherwise attributed are from this article).

Barbara Newman (aka Mona Alice Jean Newman) presented the most complete account in English of the Guglielmites in her From Virile Woman to WomanChrist: Studies in Medieval Religion and Literature, but it is in her more recent paper, “The Heretic Saint: Guglielma of Bohemia, Milan and Brunate,” that we learn important details that make an attribution to Maifreda as Papess much stronger than previously thought (all quotes and information not otherwise attributed are from this article).

Many tarot scholars since Moakley have doubted Maifreda as source, nor do they give much credence to an older assumption that the card depicted Pope Joan (see article by Ross Caldwell). Instead, modern thinking proposes that it was always an allegorical image of Fides (Faith—see Giotto image to right), Sapientia (Wisdom), Ecclesia (Holy Mother Church) or the Papacy itself. Here’s an image from the Vatican itself:

Alternately, she could be Isis (see below with Hermes Trismegistus & Moses by Pinturicchio in the Vatican), the Blessed Virgin Mary or a priestess of Venus (below) —see especially Bob O’Neill’s “Iconology of the Early Papess Cards” and Andrea Vitali’s essay on “The High Priestess.” Even Paul Huson in Mystical Origins of the Tarot finds it difficult to believe the Visconti family would memorialize a family member burned at the stake as a heretic.

Certainly “Faith” and “Holy Mother Church” may be referenced in the Tarot image, but they were probably of a more heretical sort than the orthodox church has ever sanctioned. Andrea Vitali recounts a summary of the trial of Guglielma and her followers in which we find:

“As Christ was true God and true Man, in the same manner, she [Guglielma] claimed herself to be true God and true Man in the female sex, come to save the Jews, the Saracens and the false Christians, in the same way as the true Christians are saved by means of Christ.” [Tying her story in with the final cards of Judgment and the World, we find,] “She too claimed she would arise again with a human body in the female sex before the final resurrection, in order to rise to heaven before the eyes of her disciples, friends and devotees.”

“As Christ was true God and true Man, in the same manner, she [Guglielma] claimed herself to be true God and true Man in the female sex, come to save the Jews, the Saracens and the false Christians, in the same way as the true Christians are saved by means of Christ.” [Tying her story in with the final cards of Judgment and the World, we find,] “She too claimed she would arise again with a human body in the female sex before the final resurrection, in order to rise to heaven before the eyes of her disciples, friends and devotees.”

O’Neill objects that “beyond the deck specifically produced for the Visconti about 1450, the local Milanese phenomenon of Guglielmites is unlikely to be the source for the image on earlier decks, for example, the 1442 deck mentioned in an inventory of the Este estate in Ferrara.” But, as Newman’s paper points out, Matteo Visconti’s son, Galeazzo, married the Duke of Ferrara’s sister in 1300 and lived there from 1302-1310, so Ferrara had its own early connection to this saint. Furthermore, Guglielma’s story and veneration were popularized in Ferrara by 1425 through a hagiography (saint’s life) by Antonio Bonfadini, and in Florence through a popular late-15th century religious play by Antonia Pulci—although they garbled her history. (15th century deck on the right is known as the Fournier/Lombardy II.)

Matteo Visconti (first Duke of Milan and first cousin to Maifreda) had as an advisor his good friend,  Francesco da Garbagnate—an ardent devotee of Guglielma. Matteo was at the center of his own long battle with the Church, having expelled the Papal Inquisitors in 1311, and being himself excommunicated in 1317, tried for sorcery and heresy in 1321, and having Milan placed under interdict in 1322. Matteo’s grandmother and uncle (archbishop of Milan) had earlier been named heretics. (Pope/Papess? card, left, is from the “Cary Sheet” found at the Sforza Castle, Milan.)

Francesco da Garbagnate—an ardent devotee of Guglielma. Matteo was at the center of his own long battle with the Church, having expelled the Papal Inquisitors in 1311, and being himself excommunicated in 1317, tried for sorcery and heresy in 1321, and having Milan placed under interdict in 1322. Matteo’s grandmother and uncle (archbishop of Milan) had earlier been named heretics. (Pope/Papess? card, left, is from the “Cary Sheet” found at the Sforza Castle, Milan.)

From Newman’s article, we learn that Maifreda’s convent was in Biassono, but she fails to note that Biassono is only five miles from the small town of Concorezzo that in 1299 was home to 1,500 Cathars. (I’ve since been told that this source is wrong and that most of the Concorezzo Cathars were burned as heretics or driven out by 1230). After the Albigensian crusade many small towns around Milan became refugee outposts of this faith, of which Concorezzo was a center, and may have inspired the order of nuns who called themselves the “humble” (umiliati)—[correction: the Cathar influence on other groups is not known.]

The most compelling bit of data making the attribution of the Papess card almost certain is that between 1440 and 1460 Bianca Maria Visconti, wife of Francesco Sforza and duchess of Milan, frequently visited Maddalena Albrizzi, Abbess of monasteries in Como and Brunate, and gave aid and gifts to the Order. (Brunate is just north of Milan with Biassono between them). Even the stones for the Como monastery were donated by Francesco Sforza. The Visconti-Sforza deck (first picture in post) was probably commissioned by or for Bianca Maria. Around 1450 (the same period as the deck) a cycle of frescos were painted in the Church of San Andrea at Brunate that recorded the story of Guglielma:

“How she left the house of her husband, came to Brunate, and lived a solitary life here, wearing a hairshirt and ordinary dress . . . in the company of a crucifix and an image of Our Lady.”

Only one of these frescos, ornately framed, remains today near the original chapel that had been dedicated to Saint Guglielma (see above). It depicts Guglielma with two figures kneeling before her. She appears to be giving a special blessing to a nun. Newman identifies the two as Maifreda and Andrea Saramita (he was the main promulgator of her divinity as the Holy Spirit). Others, more convincingly, claim them as Maddalena Albrizzi (founder of the monastery and candidate for sainthood) and her cousin Pietro Albrici who renovated the church. Even as late as the nineteenth century, Sir Richard Burton, author of The Arabian Nights, noted that “Santa Guglielma, worshipped at Brunate, works many miracles, chiefly healing aches of head.”

It seems reasonable to conclude that Bianca Maria Visconti may have had a special devotion to the woman whom, 150 years after being condemned by the Inquisition, so many Lombards venerated as a saint, and that she honored an earlier family member, Maifreda, who served as Guglielma’s Vicar—hiding her in plain sight as an allegory of Faith.

Let’s ask the question about the source in a slightly different way: Would it have been possible for Bianca Maria Visconti to have not seen this card as Maifreda? Likewise, would it have been possible for a church reformer of the time, familiar with Maifreda and Pope Joan, to have not seen this card as an allegory of Heresy instead of Faith? For instance, a monk wrote in Sermones de Ludo Cum Aliis (c. 1450-1480) about La Papessa, “O wretched, it is what the Christian Faith denies.”

Let’s ask the question about the source in a slightly different way: Would it have been possible for Bianca Maria Visconti to have not seen this card as Maifreda? Likewise, would it have been possible for a church reformer of the time, familiar with Maifreda and Pope Joan, to have not seen this card as an allegory of Heresy instead of Faith? For instance, a monk wrote in Sermones de Ludo Cum Aliis (c. 1450-1480) about La Papessa, “O wretched, it is what the Christian Faith denies.”

I’d be remiss to not mention the very real possibility that the Popess represented St. Clare of the Poor Clares, the female branch of the Franciscans (right).

I’d be remiss to not mention the very real possibility that the Popess represented St. Clare of the Poor Clares, the female branch of the Franciscans (right).

Or, perhaps she was simply the Church in contradistinction to the State as seen below in which a Popess and Empress represent each of these.

Later Swiss, Germans and Belgians de-sacralized the deck, finding both Pope and Papess objectionable and substituting for them cards like Jupiter & Juno, Bacchus & the Spanish Captain, or the Moors. The Papess, it seems, has always been a mysterious and disturbing force, spreading anxiety instead of the calm assurance one might expect from Faith.

Acknowledgements: Huck Meyer pointed out this picture and Newman’s article at Aeclectic’s tarotforum last year – see discussion. I was then reminded of this material through reading Helen Farley’s fascinating book, A Cultural History of Tarot: From Entertainment to Esotericism. Check out Ross Caldwell’s webpage on the Papessa and Alain Bougearel’s post on Catharism and other heresies of the period here.

A book called The Kybalion: A Study of the Hermetic Philosophy of Ancient Egypt and Greece by Three Initiates was published in Chicago in 1912. It presented seven fundamental working principles of Hermeticism. But, what is Hermeticism?

A book called The Kybalion: A Study of the Hermetic Philosophy of Ancient Egypt and Greece by Three Initiates was published in Chicago in 1912. It presented seven fundamental working principles of Hermeticism. But, what is Hermeticism?

At the base of the occult tarot and especially the tarot of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the Builders of the Adytum (BOTA) lies a philosophical system or religious philosophy. It derives from a series of anonymous writers who used the nom de plume Hermes Trismegistus (Thrice-Blessed), a composite of the Greek Hermes, Roman Mercury, and their Egyptian counterpart, Thoth. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries C.E., the set of writings known as the Corpus Hermeticum brought about a brief renaissance of pagan thought. Read the rest of this entry »

Several cards printed with curious effigies tumbled onto the floor. The first corresponded to a woman wearing the Franciscan habit, a triple crown on her head, a cross like that of Saint John the Baptist in her right hand and a closed book in her left. . . . “You’ll never open the priestess’ book,” the pilgrim said.

Javier Sierra’s novel The Secret Supper tells the story of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of “The Last Supper” (or more properly the “Cenacolo“—a circle of companions who meet together). The novel takes us through an experience like that advised by Leonardo himself: Read the rest of this entry »

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Recent Comments