You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Tarot History & Research’ category.

Tarot Art and History Tour of Northern Italy

September 23rd – October 6th 2012

14 Day Tour of Northern Italy

We had such a great time on our first organized Tarot Art & History Tour of Italy this fall, that Arnell and Michael are doing it again and it is going to be fabulous! Highlights are posted on this webpage . More details will be sent to you upon request. Hope you can come as it is an unbelievable opportunity! Please book early as space is limited for this extraordinary adventure.

Above is my photo of the room of Good and Bad Government in the Civic Palace of Siena. I really got that these frescoed rooms were designed to have a powerful impact on all who entered the space—to magically imbue people with the ideals and principles governing them. Town councilors entered the room from the now-sealed door that is directly under the allegorical images of Wisdom and Justice—a very deliberate choice. The Rider-Waite Empress was taken from the central image representing PAX (Peace). To the right is the well-governed town. To the left is the Devil with all the terrible consequences that his reign could have upon on the area. Ellen Lorenzi-Prince, creator of The Tarot of the Crone, Tarot Paperdolls and the forthcoming Minoan Tarot is in the foreground.

I can’t emphasize enough, that if you want to have any idea of the world from which the Tarot emerged, you have to experience it for yourself! Your days will be filled with the consciousness and beauty of the 14th and 15th centuries that created the base for the later Renaissance. You’ll begin to understand in the constant mix of Pagan and Christian imagery, how their “Christian” mind-set was an amalgam of all the wisdom that had come before and very different from how we think today. You’ll get an appreciation of the incomparable beauty of Italy and the sophisticated allegorical thinking that had to go into the creation of the Tarot. Your tour guide, Morena Poltronieri of the Museo dei Tarocchi, will introduce you to the secrets of the masons who built the churches and will reveal the influences of the real alchemists, Templars, artists and philosophers who left their easily discerned marks on the buildings she knows so well. Here is one corner of the Museo dei Tarocchi.

Check out this animoto video by Tero Hynynen of photos from the last trip.

As promised, here is the information on the IndiGoGo fundraising campaign for the Waite-Trinick Tarot Book. You can help publish A.E. Waite’s Second Tarot images as quickly as possible—so we can all get them in our hands! Be part of this historic presentation.

As promised, here is the information on the IndiGoGo fundraising campaign for the Waite-Trinick Tarot Book. You can help publish A.E. Waite’s Second Tarot images as quickly as possible—so we can all get them in our hands! Be part of this historic presentation.

Tali Goodwin has started a series on her discovery of the images and the continuing saga involving her research into John Trinick. Read all about it at The Tarot Speakeasy.

Update: Ordering information here for the 250 copy limited edition.

Update: Ordering information here for the 250 copy limited edition.

The following announcement by Tali Goodwin and Marcus Katz has stirred quite a controversy. At the end of this announcement you’ll find a link to an article by Tabatha Cicero that adds much to an understanding of issues involved in the publication of these images.

Tali Goodwin of Tarot Professionals and the blog Tarot Speakeasy, through extensive research, has discovered the ORIGINAL Waite-Trinick images that comprised a tarot deck conceptualized by A.E. Waite for the private use of members of his Fellowship of the Rosy Cross. Tali tracked the family of stained glass artist, J. B. Trinick, who had lived in Kendal, England, and found the original color paintings!

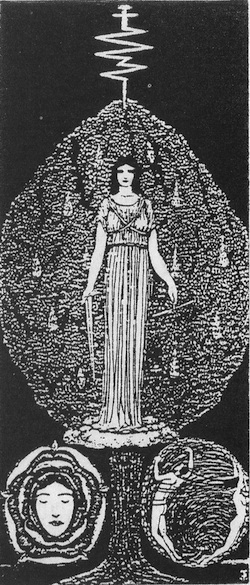

Late last year Marcus Katz stumbled across an ebay sale for a set of worn and damaged images that he immediately recognized as part of a mysterious second Waite deck. It had been brought to the attention of tarotists in Ronald Decker and Michael Dummett’s book A History of the Occult Tarot. The illustrations here are from that book. The new discovery was part of a series of several major synchronicities in the story of this rare deck that have taken place over the last two years.

Tali and Marcus were able to view and photograph the beautiful and enigmatic original paintings and have agreed with the owners to bring out a book (in color and b&w) of the major twenty-two images with full commentary prior to Christmas 2011.

The commentary will be based on Waite’s unpublished and extensive commentary on the images, which has led to a complete mapping of Waite’s “secret” correspondences to the Tree of Life. Marcus says that this set of correspondences is so blindingly obvious and “makes sense,” such that he believes we will be astounded. It will be interesting to see if the mapping corresponds with the revised Tree of Life described in Decker and Dummett’s book. Also, this clears up a long-running controversy about whether the Rider-Waite-Smith deck was designed with Golden Dawn Tree of Life Associations in mind. My feeling is that it was, as Waite clearly uses these associations in some of his Order papers, but it’s also clear that he wasn’t really satisfied with them.

Tarot Professionals are hosting a funding drive—live on Indigogo (now available) to ask for assistance towards publication. As they want to make these remarkable images—and the biggest discovery in Tarot this century—available to everyone. I’ll post the information as soon as I get it.

For additional information and another perspective, read Tabatha Cicero on “The Great Symbols of the Paths” at The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn blog.

About John Trinick

About John Trinick

About John Trinick

x

Several years ago, Cerulean, on Aeclectic’s tarot forum, posted this information about Trinick:

John Trinick was born in Melbourne, Australia, on 17 August 1890, sailing to England with his parents in 1893 before returning to Australia in 1907. He studied in the art school of the National Gallery of Victoria between 1910 and 1915 and then returned to England in 1919 to continue his studies at the Byam Shaw and Vicat Cole school of Art.

Trinick began to specialise in glass in 1921 when he joined the studios of William Morris Merton and ten years later he opened his own studio in Upper Norwood, London. He rapidly became famous for the quality of his work, exhibiting widely at The Royal Academy, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool and in Vitoria, Spain, in addition to providing stained glass windows for several churches, including a complete set of chapel windows for St. Michael’s in 1951. Among his other work was a panel, Opus Sectile, depicting Our Lady of Walsingham in Westminster Cathedral; 11 windows for St. Pius X, London and the entire chapel scheme for Salmerston Grange, Margate.

He was also an accomplished illustrator in watercolour, pencil, pastel and crayon, a collection of Trinick’s watercolour copies of European stained glass windows ws purchased by the Victoria and Albert Museum, where it forms part of the V and A archives.

Although the majority of Trinick’s work involved ecclesiastical commissions, he did not limit his exploration of spirituality to Christianity. He actively explored many modes of thinking throughout his life, including Rosicruianism and Freemasonry. He had a strong interest in alchemy and other forms of ancient spirituality. In 1922 he published a book of poetry entitled Dead Sanctuary and, in 1967, at the age of 84, he published a philosophical volume, The Fire Tried Stone, an appraisal of the work of Carl Jung.

John Trinick died in 1974, many of his designs returning to Australia.

This color design for five stained glass windows is in the University of Melbourne Art Collection.

Here’s his St. Theresa Window from Our Lady of Dolours, Hendon.

Updated: May 10, 2017

Here is the advice of 45 experienced reader and teachers of tarot and a few newbies. The contradictions are intended to foster respect and understanding for alternate views.

History is based on facts and therefore can express only what can be demonstrated with evidence or carefully deduced from an in-depth understanding of the facts, the culture, the period and the people. New facts can totally change what was formerly thought to be true.

Myths are false stories that reveal some kind of inner Truth. That Truth is often not what the myth conveys on its surface. Someone called them “the Great Imaginings behind this World.” However, they can lead us along paths that aren’t real or can even be harmful, for instance when they become “rules” that unnecessarily limit our experience.

It’s been said that history is true on the outside but a lie on the inside (for instance, we’ll never know what people actually felt and did). Whereas a myth is a lie on the outside and true on the inside (however, discerning the truth it points to can be tricky).

There are at least two kinds of tarot myths:

- Stories of tarot’s origins (mostly romantic and mystical stories with great inner significance),

- “Rules” that should be followed only if you find them helpful and meaningful.

We actually know quite a bit about tarot history:

It originated sometime between 1420 and 1440 in Northern Italy, probably in the court of Milan or Ferrara or possibly even Florence, amid other experiments in creating a suit of triumphal cards. We also know fairly precisely what the images signified in the “High Gothic”-to-early-Renaissance Italian culture. A trip to Northern Italy will confirm the ubiquitous nature of the allegorical images in the late 14th and early 15th centuries.

Playing cards (as shown below) appeared in Europe and spread quickly about 60-75 years before the Triumphs were added to the deck. For the first 350 years ‘Il Trionfos’ were known almost entirely for playing games similar to whist or bridge as attested to by several frescos and text references.

While there are are rare indications early on that both playing cards and tarot were used for divination and character delineations (in poems called Tarocchi Appropriati), true “reading” practices were not widely known until the late 18th century. This is when Antoine Court de Gébelin, Le Comte de Mellet, and Jean-Baptiste Alliette (Etteilla) wrote about tarot and fortune-telling and made up stories about their being brought to Europe by the gypsies from their mystical place of origin in Egypt (none of which has been substantiated in the slightest). Likewise, the idea of Tarot originating with either Jewish or Christian Kabbalists or with the Cathars has not a shred of evidence, even though both were known to exist in Milan during the period. Regarding the 22 Hebrew letters, early references always describe the Trumps as numbering 21, with a separate mention for the Fool (or ‘Excuse’) card.

There is still a lively debate about the etymology of the plural word Tarocchi for the deck and Tarocco for the game (which was shortened at least a hundred years later in central Europe to Tarot, Taroc or Tarock). My favorite origin story is that the root of Tarocchi is similar to that for the Sicilian Blood Orange, Tarocco, that has a pitted skin. This makes it look like the hammered gold leaf backgrounds of early court decks, from the Arabic word for ‘hammered’ (taraqa) describing a design technique used on gold and leather.

Please read Sherryl Smith’s Tarot History Chronology, TarotL History Information Sheet and my post: “Origins of Cartomancy (Playing Card Divination).” The serious student will want to check out trionfi.com, Cultural Association “Le Tarot”, the Tarot History Forum and Tarot History & Iconography at aeclectic, among others. Books are recommended on these sites and here.

The advice given here regarding the importance of history by our panel of tarot experts (and a few newbies) wasn’t easy to organize. I’ve done quite a bit of condensing and of merging of similar statements. Personally, I was originally intrigued by the myths as they supported my interest in esoteric studies and in doing readings. It was only later that I came to truly appreciate the vital importance of history and how it adds great depth my understanding of the meaning of the cards. Factual history adds to our knowledge; it doesn’t subtract from it.

Anti-History

• Just starting to read tarot? No, it’s not important to know tarot history and myth. All that’s important to know is that tarot is a divination tool.

• History is not necessary for newbies. Myths and archetypes work even if you don’t know how or what their history is. They are timeless, that is, relevant to all times. Newbies need the Magic first!

Do you want to know how playing cards are actually made? Here are a series of videos that take you through the historical development of the major deck production techniques.

This video from the Victoria & Albert Museum in London shows how woodcut playing cards were created:

The Rider-Waite-Smith deck was produced by Lithography (technically chromolithography as several colors were involved). The process was similar to what’s shown here except with a really big stone, a big press, and a separate run for each color:

Cartamundi in Belgium, who have printed many modern tarot decks, demonstrate how they print their playing cards:

I really hesitated about including this video, as it breaks my heart, but, since so many tarot decks are now printed in China, I thought it important that we understand a little of what is involved in obtaining such cheap prices:

And for something a little more personal—

Check out these sites:

- Guides for Producing Small Editions of Hand-made Playing Cards,

- Arnell Ando’s Useful Notes on Making and Publishing Your Own Tarot Deck.

If you don’t want to design your own deck but like a bit of handwork and a deck that looks different and, in many cases, is more immediate in its impact, try cutting off the borders of one of your decks. Tarotforum has a page with pictures of hundreds of trimmed tarot decks—check out which ones work best here first. And, here’s a video by Donnaleigh on how to do it:

Who created the first tarot deck? For what purpose? No one really knows for sure. It is clear that tarot cards (il trionfos) were used for games almost from the beginning. Whether there was any other purpose in the mind of the artist or the person who commissioned the deck will probably never been known. What has emerged, though, is an image of cards as a social pasttime that may have been part of the courting rituals of the period. It presented an opportunity for young men and women to interact and flirt in a chaperoned environment. In fact, two oldest decks we have, the Visconti-Sforza and the Cary-Yale Visconti, were probably commissioned as wedding presents. One of the earliest of card players and the intended recipient of the Visconti-Sforza Tarot deck, was Bianca Maria Visconti (1425-1468), shown above at her wedding with Francesco Sforza (1441). The deck may have been a gift from her father, Filippo Maria Visconti (died 1447). Filippo Maria Visconti’s golden ducato is shown on the suit of Coins of the Visconti-Sforza deck (first noticed by Ross Caldwell, I believe):

A German historian of women in the Middle Ages and Renaissance and a recognized art expert, Maike Vogt-Luerssen, has written a book about Bianca Maria (unfortunately only in German) and has collected an astonishing array of paintings of members of the Visconti and Sforza families. Begin here and then continue your tour through this marvelous collection.

Maike Vogt-Luerssen has identified the woman on the left of this famous fresco from the Borromeo Palace in Milan as Bianca Maria Visconti, mentioning only the elaborate hair design as her reason.

Was the possibly later Cary-Yale Tarot cards, a deck with six court cards per suit and additional triumps, made for the marriage of

Was the possibly later Cary-Yale Tarot cards, a deck with six court cards per suit and additional triumps, made for the marriage of

- Filippo Maria Visconti and Marie of Savoy in 1428 (because it contains the Savoy device of a white cross on a red field), or for

- Galeazzo Maria Sforza with Bona of Savoy in 1468 (because it contains the Sforza device of a fountain)?

Marie of Savoy was the daughter of Amadeus VIII, Count of Savoy, who was elected as the Antipope Felix V by the Council of Basel-Ferrara-Florence, from November 1439 to April 1449 (the picture of Felix V on the right should be familiar to tarot aficionados):

There is a possibility that the Cary-Yale cards were painted not by Bonifacio Bembo (who was the most likely artist of the Visconti-Sforza deck) but by someone from the workshop of the Zavattari family (and here) who painted the frescos of Teodolinda in the Cathedral at Monza, near Milan.* The Bavarian and Christian Teodolinda married the Lombard king Authari in 589 (who was either an early heretic or a pagan) and when he died a year later, she married the Duke of Turin, Agilulf, who became the King of Italy, making Milan his seat. In the 15th century, the Zavattari family painted the story of Teodolinda, as she had founded a chapel on that spot and established Monza as her home. These frescos bear a striking resemblance both to the Borromeo frescos and to the Cary-Yale Tarot. Note especially the braided hair, slit sleeves, and the young man/page with his hand grasping his belt in both the Monza fresco (first), followed by four cards from the Cary-Yale deck.

Added: Tero Tynynen has done more research on the subject with lots of links and a couple of videos featuring the frescos of Monza and period music, for those who are interested in the possible artists of these earliest decks – here.

* The frescos in the Cathedral of Monza were painted between 1440 and 1446 by Franceschino Zavattari and his sons Gregorio and Giovanni in a style known as the “International (or Late) Gothic.” Another son, Ambrogio, may have been involved. Franceschino’s father, Cristoforo, participated in work on the Milan Cathedral in the early fifteenth century. Slight differences in style are probably due to different painters within the family as well as the difference between large wall frescos and small cards. It should be noted that I am not the first to see these similarities, as they’ve been noted by many commentators, but the information is not generally known among tarot readers.

For a really wild surmise regarding the story of Teodolinda, I can’t help wondering if the story of the Christian bride converting a pagan king named Authari (Arthur?) and being led by a dove to build a cathedral could have been at all related to the King Arthur legend, that became popular in 15th century Lombardy?

Lady luck is shining brightly on an archivist from the canton of Nidwalden [Switzerland]. While restoring the cover of a medieval court record last week, he uncovered 90 playing cards dating from 500 years ago. The chance find is only four cards shy of a complete set. And the discovery is one of only a handful to yield a group of so many cards of this vintage for a game seen as a predecessor to one of Switzerland’s national pastimes. . . . The cards probably date from 16th century Basel.

Lady luck is shining brightly on an archivist from the canton of Nidwalden [Switzerland]. While restoring the cover of a medieval court record last week, he uncovered 90 playing cards dating from 500 years ago. The chance find is only four cards shy of a complete set. And the discovery is one of only a handful to yield a group of so many cards of this vintage for a game seen as a predecessor to one of Switzerland’s national pastimes. . . . The cards probably date from 16th century Basel.

Read the article at World Radio Switzerland.

Not many people realize that one of the most outstanding museums dedicated to tarot is in Heffen-Mechelen, Belgium. Guido Gillabel has recently posted a large number of photos documenting his collection on his Facebook Page (open to all). The museum can be visited in person by appointment. I’m posting a few pictures to give you an idea what to expect from his virtual tour. You’ll find plenty of close-ups. I’ve seen lots of decks and artifacts that I never knew existed and things that have been on my wish-list since forever. Can you find any gems that you’d like to have—like tarot socks or statues in the style of Niki de St.Phalle!

After exploring five hundred years of the moralization of playing cards in Part 1 and Part 2, we finally get to playing cards and, eventually, tarot, as a book of wisdom. I included this section under the theme of “moralization” because it shows a development of this theme into social-spiritual-political reform and a shift from an orthodox Christianity to a Humanism that arose in the Renaissance and Enlightenment. We see here that playing cards (and/or tarot) have been viewed, on occasion, as a book of the wise, teaching a timeless philosophy leading to the betterment of humankind. I’d like to preface this section with a reminder of the origins of the occult tarot.

Radical Social Reform and the Hieroglyphs of the Wise

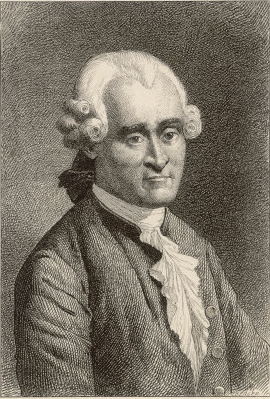

In 1781 Antoine Court de Gébelin (actually Antoine Court, from Gébelin), son of a famous Huguenot pastor, published an essay in his encyclopedic work, Le Monde Primitif, in which he declared the tarot came from Egypt and was related to the Hebrew letters. The text of Court’s essay and an accompanying one by Le Comte de M[ellet] has elements that suggest that these ideas about tarot did not originate with them, but were possibly based on materials available in French Masonic lodges (to which Etteilla also belonged). The early-19th century magician Eliphas Lévi hints at this:

In 1781 Antoine Court de Gébelin (actually Antoine Court, from Gébelin), son of a famous Huguenot pastor, published an essay in his encyclopedic work, Le Monde Primitif, in which he declared the tarot came from Egypt and was related to the Hebrew letters. The text of Court’s essay and an accompanying one by Le Comte de M[ellet] has elements that suggest that these ideas about tarot did not originate with them, but were possibly based on materials available in French Masonic lodges (to which Etteilla also belonged). The early-19th century magician Eliphas Lévi hints at this:

“The true initiates, contemporaries of Etteilla, the Rosicrucians, for example, and the Martinists, who were in possession of the real Tarot . . . were far from protesting against the errors of Etteilla, and left him to re-veil, not reveal, the arcanum of the veritable claviculae of Solomon.” (Lévi, Mysteries of Magic, p. 270)

The fact that Egypt is given as the source of the tarot was not unexpected, because Court’s encyclopedia was an allegorical examination of ancient mythologies (which he believed began in agriculture). This led to a search for the origin of language and the remnants of original hieroglyphs that he saw as containing the symbolic and mystical knowledge of the wise. He attempted to catalog the universal mother tongue and grammar by deciphering all traces of the primal language still extant in the modern world. The tarot was, to his mind, one of these hieroglyphic languages. A powerful advocate of radical social reform, including freedom of religion and of independence in America, Court believed that reconstructing this proto-language would bring about social-regeneration through “a single grammar of physics and morality,” allowing “modern men nothing less than a chance to uncover the timeless, natural laws governing human happiness, and thereby to restore peace and prosperity on earth” (see Rosenfeld). In addition to the Masonic lodge of Les Neuf Sœurs (“Nine Sisters”), which he co-founded, Court was a prominent member of the Order of Philalethes (founded 1773), who, as scholarly ‘Searchers of Truth,’ were on a mission to track down everything that could be found on the occult sciences in Freemasonry. Another member was Cagliostro, famous for his institution of an Egyptian Rite in French Freemasonry. I’ve not found any written reference to Cagliostro and tarot, but he gained his reputation, in part, as a successful fortune-teller and was depicted in the following illustration as a cartomancer.  Antoine Court de Gébelin was not the first to envision such a socio-political regeneration in which the tarot cards would play at least an oblique part.

Antoine Court de Gébelin was not the first to envision such a socio-political regeneration in which the tarot cards would play at least an oblique part.

The Italian Connection & The New-Found Politicke

In 1612, an Italian who reported on (and satirized) the political, moral and literary issues of the day and advocated religious tolerance, Trajano Boccalini (1556 –1613) published in Milan, I Raggvagli di Parnasso (“Advertisements from Parnassus;” also De Ragguagli di Parnaso, see article by Andrea Vitali, in which he asserts that the game played was probably with ordinary playing cards, not tarot). Parnassus was the mountain of poets, an equivalent to the Olympus of the gods. First printed in Milan, the work was frequently translated and republished—first in England by John Florio and others who called it The New-Found Politicke (1626). It contained a chapter on cards, possibly tarot, although Vitali (above) identifies them as regular playing cards.

John Florio was born in England to an Italian father who had fled the persecution of the Waldenses in Florence. Florio was raised in both cultures, translating Italian ideas for English usage.  Shakespeare’s reference to the card game of Triumph in Antony and Cleopatra is believed to have been inspired by Florio’s Second Frutes of 1591, whose Italian proverbs and figures of speech had a great influence on the literature of the period (or Shakespeare may even have been Florio, according to Jorge Louis Borges).

Shakespeare’s reference to the card game of Triumph in Antony and Cleopatra is believed to have been inspired by Florio’s Second Frutes of 1591, whose Italian proverbs and figures of speech had a great influence on the literature of the period (or Shakespeare may even have been Florio, according to Jorge Louis Borges).

“Wrap Excellencie up never so much,

In Hierogliphicques, Ciphers, Caracters,

And let her speake never so strange a speech,

Her Genius yet findes apt discipherers.”

It was in Florio’s Italian-English dictionary of 1598 that the English learned that Tarocchi are “a kind of playing cards used in Italy, called terrestrial triumphs” and that taroccare means “to play at Tarocchi”; also “to play the froward gull or peevish ninnie” (that is, “to play the contrary fool or whining simpleton”). Frances Yates theorized in her book John Florio: the Life of an Italian in Shakespeare’s England (1934) that Florio acted as intermediary between Shakespeare and Giordano Bruno with his neoplatonic hermeticism. Florio worked under the patronage of the Earl of Southampton who was also Shakespeare’s patron and was under the patronage of both Archbishop Cranmer and Sir William Cecil—in whose house he lived for some time. These were both close friends of Hugh Latimer (see Part 1)—small world!

Getting back to Boccalini’s I Raggvagli di Parnasso (from the translation by Henry Cary, 1669): We find in the “2nd Advertisement” a short text from the start of a large work that might be thought to contain material that will inform the whole. It follows the same initial plot as the “Soldier’s Prayerbook” (see Part II) in which a young rapscallion is discovered with cards, taken before an authority to explain himself, at which time the deep mysteries of the cards are revealed, although in this case, it is the authority, Apollo, who discerns them. He explains that the game of Trumps (see Part 1) teaches hidden secrets and ‘a science necessary for all men to learn,’ a ‘true Court-Philosophy’ in that even the most worthless trump takes all the ‘beautiful figures.’ Later we will see that, to the masses, even the least-of-trifles trumps all the great wisdom of the sages. It is a satiric commentary that masks a deeper philosophy, just as to more modern tarot commentators, the triviality of tarot as a gambling game was believed to hide its higher truths.

The usual Guard of Parnassus having taken a Poetaster*, who had been banished [from] Parnassus, upon pain of death, found a paire of cards in his pocket; which when Apollo saw, he gave order that he should read the Game of Trump in the publick Schools [my italics].

*Poetaster, like rhymester or versifier, is a contemptuous name often applied to bad or inferior poets. Specifically, poetaster has implications of unwarranted pretentions to artistic value.

[The text concludes with:] Apollo asked this man, what game he used to play most at? Who answering, Trump, Apollo commanded him to play at it; which when he had done, Apollo penetrating into the deep mysteries thereof, cryed out, that the Game of Trump, was the true Court-Philosophy; a science necessary for all men to learn, who would not live blockishly. And appearing much displeased at the affront done this man, he first honoured him with the name of Vertuoso; and then causing him to be set at liberty, he commanded the Beadles, that the next morning a particular College should be opened, where with the salary of 500 crowns a year, for the general good, this rare man might read the most excellent Game of Trump; and commanded upon great penalty, that the Platonicks, Peripateticks, and all other the Moral Philosophers, and Vertuosi of Parnassus, should learn so requisite a science; and that they might not forget it, he ordered them to study that game one hour every day; and thought the more learned sort thought it very strange that is should be possible to gather anything that was advantagous for the life of man, from a base game, used only in ale-houses; yet knowing that his Majesty did never command anything which made not for the bettering of his Vertuosi, they so willingly obeyed him, as that school was much frequented. But when the Learned found out the deep mysteries, the hidden secrets, and the admirable cunning of the excellent Game of Trump, they extolled his Majestie’s judgement, even to the eighth heaven, celebrating and magnifying everywhere, that neither Philosophy, nor Poetry, nor Astrologie, nor any of the other most esteemed sciences, but only the miraculous Game of Trump, did teach (and more particularly, such as had business in Court) the most important secret, that even the least Trump, did take all the best Coat-Cards” [“che ogni cartaccia di Trionfo piglia tutte le più belle figure”].

The Rosicrucians and a Universal Reformation of the World

Meanwhile, in Kassel, Germany a revolutionary paper with far-reaching consequences was being written by a young Johann Valentin Andreae and friends who were part of a utopian brotherhood. The supposedly anonymous Fama Fraternitatis or Rosicrucian Manifesto was published in 1614 and had an impact that no one could have imagined. It tells the story of Christian Rosenkreutz who traveled to the Middle East where he met sages and mystics, learning from them esoteric wisdom and knowledge before returning to Europe where he founded the secret Brotherhood of the Rose Cross (the Rosicrucians). This secret order consists of men, dedicated to the well-being of humankind, who travel the world healing and teaching. It gives an account of their discovery of the hidden tomb of Rosenkreutz, whose body lies, in centre of the vault, perfectly preserved after the passing of over a century.

The Fama first appeared with a preface: “Advertisement 77” of Boccalini’s just published I Raggvagli di Parnasso that called for a “Universal Reformation of the World.” Although it doesn’t mention cards directly, we saw that an earlier chapter did. Its purpose regarding the Fama has been much debated because the follies of these reformers of the world are openly ridiculed. “Advertisement 77” depicts a fraternity of the world’s wisest men who debate many ideas about how to resolve the world’s conflicts. Despite their belief in the high principles of love and caritas, they conclude that the masses will always prefer relief of their immediate problems over the true reform of society. And so they lower the prices of essential foods—to great rejoicing—rather than enacting the lofty reforms they had just discussed. Boccalini despairs, not believing that intellectual enlightenment will prevail. As A. E. Waite describes it:

“They fixt the prices of sprats, cabbages, and pumpkins . . . for the rabble are satisfied with trifles, while men of judgment know that—as long as there be men there will be vices—that men live on earth not indeed well, but as little ill as they may, and that the height of human wisdom lies in the discretion to be content with leaving the world as they found it.” (Waite, The Real History of the Rosicrucians, 1887.)

One modern Freemason believes that Boccalini’s satire was making it “clear that the first step for the reformation of the world must necessarily be the reformation of the spirit.” Frances Yates suggests that the inclusion of Boccalini may, in part, have been an oblique reference to Giordano Bruno and certain “secret mystical, philosophical, and anti-Hapsburg currents of Italian origin.” She explains,

“Giordano Bruno as he wandered through Europe had preached an approaching general reformation of the world, based on return to the ‘Egyptian’ religion taught in the Hermetic treatises, a religion which was to transcend religious differences through love and magic, which was to be based on a new vision of nature achieved through Hermetic contemplative exercises.” [Yates, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 136.]

Others claim there is an alchemical interpretation for the text. Manly Palmer Hall attributes Boccalini’s chapter to Lord Verulam, Francis Bacon, known as ‘the Chancellor of Parnassus’ (his wife was a huge Bacon fan).

The Wise Men of Fez

Now, Paul Foster Case (who created the BOTA tarot) was well aware of the first edition of the Fama Fraternitatis, having written his own book on the Rosicrucian Manifesto. I also believe he was familiar with the whole Ragguagli as he seems to have blended Advertisements 2 and 77 into his tale of the origin of the tarot. According to Rosicrucian legend, Christian Rosenkreutz studied in Egypt and at length arrived in Fez, the holy city of Morocco that was, during the Middle Ages, one of the most famous centers of the alchemical arts. In The True and Invisible Rosicrucian Order, Case sets his own mythical origin of the tarot in Fez and places the wisdom of all the gathered sages into a deck of cards, whose pictures speak a thousand words, equally in all languages. He clearly wants his readers to believe that the tarot was one of the “many books and pictures sent forth” by the Rosicrucian Fraternity that could speak in many languages of their treasures: the secrets of spiritual alchemy that could bring about “general reformation both of divine and human things.” And, as Waite commented above, “as long as there be men there will be vices,” so that wisdom imparted through a tool of gambling would never be lost.

The Rosicrucians Come to France

Let us return now to France, where some believe that (in contrast to other European nations) Rosicrucianism failed to take hold. But, several scholars have noted that in 1623 a mysterious placard was affixed to the walls of Paris:

“We, the deputies of our chief college of the Brethren of the Rosy Cross, now sojourning, visible and invisible, in this town, do teach, in the name of the Most High, towards whom the hearts of the Sages turn, every science, without either books, symbols, or signs, and we speak the language of the country in which we tarry, that we may extricate our fellow-men from error and destruction.”

On the 23rd June 1623, “A general assembly of Rosicrucians was reported to have been held in Lyons” (G. Naudé, Instruction à la France sur la verité de l’histoire des Freres de la Roze-Croix, 1623, p. 31). A Rosicrucian lodge of Aureae Crucis Fraternitatis was founded in 1624. (Jean-Pascal Ruggiu, Rosicrucian Alchemy and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn). By the late l8th century, the Order of Philalethes and some other Masonic lodges had instituted Rosicrucian grades.

Pure Speculation

There are few factual historical connections among all this material. Yet there seems to be a functional connection in which the deck of cards serves as a hidden reminder, manifesting through time in a variety of forms, of moral truths and spiritual teachings. Could explorations of the sources of the Rosicrucian Manifesto by the Order of Philalethes have turned up Boccalini’s entire Raggvagli with its chapter on the Trumps? Might the Italian Cagliostro have included tarot when he was teaching his Egyptian Rite to French Masons? Hopefully, this new information should excite speculation, perhaps bring to light some overlooked facts, and encourage us to explore questions about the role of cards as carriers of ideas in human culture and philosophy.

Le Grandprêtre Tarot

Were these cards created to illustrate the text of Antoine Court de Gébelin or did they inspire his text?

The cards in this deck, from the John Omwake Playing Card Collection, have many of the same titles that appear in Le Monde Primitif. They were attributed by Catherine Hargrave in A History of Playing Cards (1930) to early 18th century France. Stuart Kaplan in his Encyclopedia of Tarot, V.1 dates them 1720, but in V.2 he changes that to late 18th century, post-Le Monde Primitif (p. 336-7). Other than this deck, the first use of the terms High Priest and High Priestess (Grandprêtre and Grandprêtresse) instead of the Pope and Popess are in LMP.

The cards are 1-7/8″x3-3/8″ and were, according to Hargrave, made from copper plates and then hand-colored, so they must have had some distribution. There is no separate Fool card, but he appears in place of the Devil on card XV.

If influenced by Antoine Court why aren’t his card descriptions followed more closely? Could the originally estimated date possibly be correct?

The Servant’s Almanac, Soldier’s Deck of Cards, or Cards Spiritualized

In Part 1, I gave examples from 1377, 1525 and 1529 of how playing cards were used for moral allegories. Sometime in the late 17th to early 18th century this trend gave birth to a popular storyline that has continued, little changed to this day. The story goes that, in order to justify carrying a pack of cards, a soldier (or a servant) explains that the deck reminds him of the calendar and of God. Some variation on this story quickly appeared throughout Europe and has continued to metamorphize in interesting ways. That the character usually mentioned is either a Richard Middleton or Richard Lee of Glasgow, suggests its origin was probably the British Isles.

The oldest example of each number card being spiritualized is found in 1666 in Belgium, in a book illustrated by cards, called Het Geestelijck Kaertspel, “The Spiritual Card Game with Hearts Trumps, or the Game of Love,” by Joseph a Sancta Barbara in which each of the Hearts cards is equated with a Christian subject. The King references God the Father, the Queen is the Virgin Mary, the Knave shows the rich and mighty [made humble?] before the Crucified Christ, the ten shows the ten commandments. Then there are the nine choirs of angels [see at right], eight Christian virtues; seven works of mercy; six goals in life; five wounds of Christ; four last ends, the three members of the Holy Family; the worship of God the Father and Mary the Mother; and the one Truth that must reside in a Christian heart. (Hargraves, A History of Playing Cards, p. 161.)

The oldest example of each number card being spiritualized is found in 1666 in Belgium, in a book illustrated by cards, called Het Geestelijck Kaertspel, “The Spiritual Card Game with Hearts Trumps, or the Game of Love,” by Joseph a Sancta Barbara in which each of the Hearts cards is equated with a Christian subject. The King references God the Father, the Queen is the Virgin Mary, the Knave shows the rich and mighty [made humble?] before the Crucified Christ, the ten shows the ten commandments. Then there are the nine choirs of angels [see at right], eight Christian virtues; seven works of mercy; six goals in life; five wounds of Christ; four last ends, the three members of the Holy Family; the worship of God the Father and Mary the Mother; and the one Truth that must reside in a Christian heart. (Hargraves, A History of Playing Cards, p. 161.)

If this sounds a little like “The Twelve Days of Christmas” you aren’t far off, since a similar catechism-type song, with religious imagery called “The Twelve Days” or “A New Dial” appeared in 1625.

The next example, known as “The Servant’s Almanac” is found in Brett’s Miscellany by Peter Brett, 1748, which I’ll quote in full as it contains the main elements found in the later versions:

A Certain Gentleman having two Servants, one Servant complained to his Master of his fellow-servant, that he was a great Player of Cards, which the Master would not allow in his family; he called for the Servant complained of, and tax’d him.

He knew not what Cards meant.

At which the Master was angry with the Complainer, and called him to hear what he could farther say; Who desired, he might be immediately searched, so he believed, he at that Time had a Pack in his Pocket. And accordingly he was searched and a Pack found in his Pocket; which he would not own to be Cards, but said: That it was his Almanack.

His Master asked him, How he made it appear to be his Almanack? His Answer was,

“There are in these Things you call Cards, as many Sorts as there are Quarters in the Year; that is four, Spades, Clubs, Hearts and Diamonds: There are as many Court Cards as there are Months in the Year, and as many Cards as there are weeks in the Year; and there are as many Pips as there are Days in the Year.”

many Cards as there are weeks in the Year; and there are as many Pips as there are Days in the Year.”

At which his Master wondered; asking him, Did he make no other Use of them ? He answered thus :

“When I see the King, it puts me in Mind of the Loyalty I owe to my Sovereign Lord the King; when I see the Queen, it puts me in mind of the same; when I see the Ten, it puts me in mind of the Ten Commandments; the Nine, of the Nine Muses; the Eight, of the Eight Beatitudes; the Seven, of the Seven liberal Sciences; the Six, of the Six Days we mould labour in; the Five, of the Five Senses; the Four, of the Four Evangelists; the Tray, of the Trinity; the Deuce, of the Two Sacraments; and the Ace, that we ought to worship but one God.”

Says the Master, “this is an excellent Use you make of them; but why did you not make mention of the Knave?”

“Sir, I thought I had no occasion to mention him, because he is here present,” clapping his Hand on his fellow-Servant’s shoulder.

By 1762, the version known as The Soldier’s Prayerbook is recorded in an account/common-place book belonging to Mary Bacon, a farmer’s wife. (Mary Bacon’s World. A farmer’s wife in eighteenth-century Hampshire, published by Threshhold Press (2010).) This seems to be the first mention of what became the best-known version.

The most famous example is from 1776 in London Magazine: or, Gentleman’s monthly intelligencer (Vol. 45), which tells the story of Richard Middleton. It begins:

The most famous example is from 1776 in London Magazine: or, Gentleman’s monthly intelligencer (Vol. 45), which tells the story of Richard Middleton. It begins:

“One Richard Middleton, a soldier, attending divine service with the rest of the regiment in a church in Glasgow, instead of pulling out a bible, like his brother soldiers, to find the parson’s text, spread a pack of cards before him . . .” [He is taken before the Mayor and asked,] “What excuse have you to offer for this strange, scandalous behaviour?” (Follow the link above for the full story.)

Histoire du Jeu de Cartes du Grenadier Richard appeared in France in 1811, but is most often found bound with an even more interesting Explication morale du jeu de cartes from 1776 (see comments for more information & thanks for the correction, Ross). Marie-Anne-Adélaïde Lenormand published it as Almanach du bonhomme Richard in 1809, and later, in 1857, the Chevalier de Châtelain included it in his translation, Fables de [John] Gay & Beautés de la Poésie Anglaise. The English poet and playwright, John Gay (1685-1732), best known for the play, “The Beggar’s Opera,” did not include it in his two volumes of Fables (although a couple of his fables feature card-players), but it could be a lost work, printed originally in broadside.

By 1926 the story had metamorphized (considerably and without the moralizing) into a magician’s card trick called The Adventures of Diamond Jack, as advertised by Herman L. Weber (Namreh) in The Sphinx. It and The Perpetual Almanac or Gentleman Soldier’s Prayer Book appear near each other in Jean Hugard’s Encyclopedia of Card Tricks (1937), showing that they are considered to be of a similar type. Another irreverent version, called Sam the Bellhop has become popular through performances by Bill Malone and James Galea, as seen in the following youtube videos.

The next (and truer) metamorphosis was as a country song, “The Deck of Cards,” first made famous by T. Texas Tyler in 1948, written about the WWII North African Campaign in the little town called Casino. It’s been recorded by at least a dozen musicians including Phil Harris, Tex Ritter, Wink Martindale (on Ed Sullivan), Max Bygraves, Hank Williams, Prince Far I, John McNicholl, and many others that can be found on youtube, including the parody, “A Hillbilly’s Deck of Cards” by Simon Crum.

This song was updated with a twist for the Korean war as “The Red Deck of Cards” by Red River Dave McEnery in 1953 (which I first heard from labor organizer and folklorist U. Utah Phillips).

“It was during the last days of the prisoner exchange in Korea, I was there as they came through Freedom Gate. Shattered, sick and lame. There in a red cross tent as the weary group rested, a soldier broke out a deck of cards. A look of hate crossed the tired face of one boy as he sprang up—knocking the cards to the ground. As the cards lay around, many of them face up, he picked up the Ace and began.

“Fellows,” he said, “I’m sorry, but I hate cards. The commies tried to use them to teach us their false doctrine. They told us the “ACE”, meant that there’s one God, the state. We knew that to be untrue for we were religious boys.” “And the “DEUCE” meant there were two great leaders. Only two. Lenin and Stalin. And we couldn’t swallow that either . . . ”

There is, of course, a Vietnam version (by Red Sovine), the Gulf war (by Bill Anderson), the 2nd Iraq war (1-with photos & 2-Al Traynor), and an e-mail variation currently circulates featuring a soldier serving in Afghanistan:

“A young soldier was in his bunkhouse all alone one Sunday morning over in Afghanistan. It was quiet that day, the guns and the mortars, and land mines for some reason hadn’t made a noise. The young soldier knew it was Sunday, the holiest day of the week. As he was sitting there, he got out an old deck of cards and laid them out across his bunk . . .”

“What does this all have to do with tarot?” you may ask.

All the above variations center on storytelling (or “destiny narration” as Cynthia Giles called it) and advice giving, plus number symbolism. Number symbolism is one of the key techniques used in interpreting the cards, and tarot authors, in writing about the meaning of numbers, often point to the same religious motifs as sources of ideas used to interpret the cards. Like the illustrated “prayer cards” above—whether simply evoked in the mind or made into a deck—they suggest a book of signs that are meant to guide us in making the best decisions. They also serve as memonic aids (for instance, the song goes, “The ten reminds me of . . . “), and the tarot was originally thought to have served as part of the Ars Memoria. And, of course, the magicians doing magic tricks perfectly emulate the patter of the Bagatto, Montebank or Magician of the Major Arcana.

The sample cards above come from a deck illustrated to match The Soldier’s Prayerbook, and are available here.

[I’ve been wondering if this story might first be found in a book I haven’t been able to access from 1613: The Carde and Compasse of Life Containing Many Passages, Fit for These Times. and Directing All Men in a True, Christian, Godly and Ciuill Course, to Arrive at the Blessed and Glorious Harbour of Heaven, a manual of advice to the prince. By Richard Middleton. It’s a long shot, but if anyone has access to the libraries holding it, I’d love them to check it out.]

Check out Part 1 on the early moral allegories, and read Steve Winick’s discoveries that he has so generously contributed to the comments on this post.

Continue on to Part 3 on Social Reformation.

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Recent Comments