When did the modern tarot renaissance actually begin? It’s always hard to pinpoint the beginning of a movement but here are some events worth noting that lead up to the breaking of the dam in 1969. I’m looking for corrections and additions to the information below, plus tarot stories from the 60s and early 70s. Please share them in the comments.

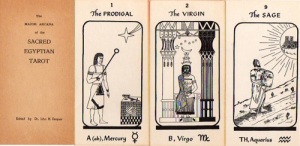

The 1940s saw some interesting tarot activities that set the stage for the later renaissance. The Crowley-Harris Thoth deck was completed and published in a limited edition of 200 in monochrome brown by Chiswick Press, but these were not available to the general public. In 1947 Paul Foster Case published his masterful work The Tarot: A Key to the Wisdom of the Ages, based on his tarot correspondence course. In France, Paul Marteau came out with his hugely influential book Le Tarot de Marseille that noted the symbolic significance of the smallest details in the deck. In Brazil, J. Iglesias Janeiro, published his book La Cabala de Prediccion, which popularized the turn-of-the-century Egyptianized Falconnier/Wegener cards. It became a center-piece of his important occult school, known mostly in Latin America. Meanwhile, in the U.S.A., Dr. John Dequer published The Major Arcana of the Sacred Egyptian Tarot, which was his revised version of those same Egyptianized cards, similar to what was already being used by C.C. Zain’s Brotherhood of Light correspondence school.

The Insight Institute in Surrey England started up their tarot correspondence course (later published in a book by Frank Lind) and produced their occultized version of the Marseilles deck (eventually published as the R.G. Tarot). Also appearing was an unusual book, solely on the psychological dimension of the Minor Arcana cards numbered 2-10 as they are associated with one’s birthday. It was Pursuit of Destiny by Muriel Bruce Hasbrouck, who had studied with Aleister Crowley when he was in the United States. Tudor Publishing’s The Complete Book of the Occult and Fortune Telling became the sole source in English of the unique Tarot card interpretations from Eudes Picard’s 1909 French work, Tarot.

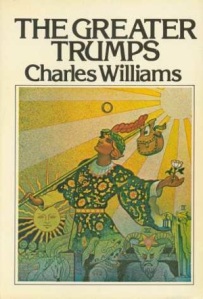

The 1940s also saw the incorporation of Tarot imagery in surrealist artworks such as Victor Brauner’s “The Surrealist,” and in Jackson Pollack’s “Moon Woman” (both of which I happened upon when I visited the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice following the 2000 Tarot Tour with Brian Williams). William Gresham’s novel, Nightmare Alley, featured a carny mentalist who reads tarot and the book is presented as a twenty-two card reading. A year later Tyrone Power played the lead in the movie version featuring two tarot readings by Joan Blondell. Charles Williams’ landmark tarot novel, The Greater Trumps came out just as this decade ended and the next one began.

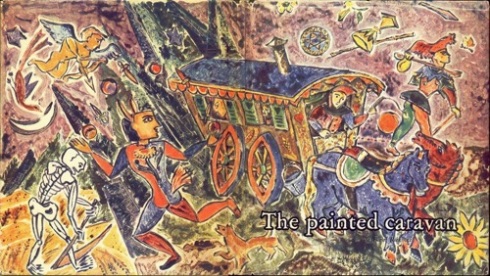

The 1950s produced even fewer tarot works. George Fathman published The Royal Road: A Study in the Egyptian Tarot, which used Dequer’s version of the Falconnier/Wegener cards. Paul Christian’s seminal work The History and Practice of Magic was translated from French to English, providing the original source material on which all those Egyptian-style decks were based. Arcanum Books reissued Papus’ The Tarot of the Bohemians with an introduction by librarian Gertrude Moakley, who noted the influence of tarot on creative writers and in psychology. Off in the Netherlands, Basil Rakoczi published the English language letterpress art book: The Painted Caravan: A Penetration into the Secrets of the Tarot Cards. Yet, the tarot seemed likely to fade away from popular view.

1960 started out the decade with a bang. University Books published Waite’s A Pictorial Key to the Tarot for an American readership, as well as a deck: Tarot Cards Designed by Pamela Colman Smith and Arthur Edward Waite. Eden Gray self-published her Tarot Revealed that still sells well to this day. In England Rolla Nordic came out with The Tarot Shows the Path: Divination through the Tarot. These last two books showed a clear shift in interest to practical tarot readings for the masses. Muriel Hasbrouck’s greatly overlooked 1940s work was re-published.

As the 60s progressed we got two heavy metaphysical works: Mouni Sadhu’s Tarot: A Contemporary Course of the Quintessence of Hermetic Occultism, and Mayananda’s The Tarot for Today, a study of Crowley’s material in the Book of Thoth (despite the latter’s being unavailable). The Brotherhood of Light came out with a new, revised edition of their 1930s Tarot deck. Idries Shah claimed, in The Sufis, that the Tarot was a Sufi creation. Influenced by T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” and Yeats’ involvement in the Golden Dawn, poets like Robert Creeley, John Weiners, Diane Wakowski, Sylvia Plath, Philip Lamantia and Diane di Prima began using tarot imagery in their poems. While not published until 1974, Jack Hurley and John Horler worked on “The New Tarot,” a Jung-based deck, at the Esalen Institute throughout the 60s, influencing many who passed through there.

In 1966 Gertrude Moakley set tarot history on it’s ear with her groundbreaking research in The Tarot Cards Painted by Bembo. The Grand Tarot Belline deck was published in Paris, as was a new edition of Oswald Wirth’s 1927 book, Le Tarot des imagiers du moyen age, that included his 22 card deck. Beginning in 1966 and running through 1971 the day-time TV soap opera Dark Shadows gave many people their first glimpse of a tarot deck as various episodes featured readings with the Marseille deck.

In 1966 Gertrude Moakley set tarot history on it’s ear with her groundbreaking research in The Tarot Cards Painted by Bembo. The Grand Tarot Belline deck was published in Paris, as was a new edition of Oswald Wirth’s 1927 book, Le Tarot des imagiers du moyen age, that included his 22 card deck. Beginning in 1966 and running through 1971 the day-time TV soap opera Dark Shadows gave many people their first glimpse of a tarot deck as various episodes featured readings with the Marseille deck.

By 1967, even a paper company jumped on the bandwagon with its advertising Linweave Tarot Pack that gave David Palladini his introduction to tarot design (see card on right). Helios Books in England published a small edition of the Golden Dawn’s Inner Order tarot teachings, Book T. Doris Chase Doane came out with two books that helped popularize the Brotherhood of Light Egyptian tarot deck in America. Sidney Bennett wrote Tarot for the Millions.

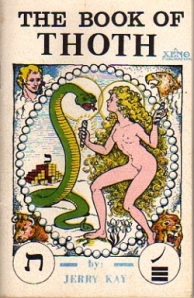

In 1968, the House of Camoin reproduced the classic 1760 Tarot de Marseille based on original pearwood woodcuts. The mysterious Frankie Albano redid Waite and Smith’s deck in brighter colors, giving those in the U.S.A. an alternative to the University Press version. Hades, in Paris, published Manuel complet d’interpretation du tarot, claiming it was based on a pre-de Gébelin 1761 original. Jerry Kay came up with his own version of Crowley’s deck that he called The Book of Thoth: The Ultimate Tarot. And, Stuart Kaplan brought back the Swiss 1JJ deck from the Nuremberg Toy Fair, selling 200,000 copies in the first year and making tarot available in department stores across the U.S.

In 1968, the House of Camoin reproduced the classic 1760 Tarot de Marseille based on original pearwood woodcuts. The mysterious Frankie Albano redid Waite and Smith’s deck in brighter colors, giving those in the U.S.A. an alternative to the University Press version. Hades, in Paris, published Manuel complet d’interpretation du tarot, claiming it was based on a pre-de Gébelin 1761 original. Jerry Kay came up with his own version of Crowley’s deck that he called The Book of Thoth: The Ultimate Tarot. And, Stuart Kaplan brought back the Swiss 1JJ deck from the Nuremberg Toy Fair, selling 200,000 copies in the first year and making tarot available in department stores across the U.S.

The stage was now set for the 1969 deluge: at least five decks and twelve separate books where published! I won’t mention them all but they included Crowley’s Thoth book and deck (though not readily available for another two years), Cooke & Sharpe’s New Tarot for the Aquarian Age, an English-language edition of Grimaud’s Marseilles deck. Also books by Arland Ussher, Brad Steiger, Corinne Heline, Gareth Knight, C.C. Zain, Hilton Hotema, Frater Achad, Rodolfo Benavides, Elisabeth Haich, Sybil Leek, and Italo Calvino’s Italian short stories, ‘Il castello dei destini incrociati (“Castle of Crossed Destinies”). Every hippie pad had its requisite tarot reader.

1970 featured fewer books but even more decks, including the Rider-Waite and Palladini’s Aquarian. Stuart Kaplan at U.S. Games, Inc. started publishing his own decks.

The Tarot Renaissance was now fully underway.

For an even more extensive look at Tarot in America from 1910 to 1960 please see this Tarot Heritage page.

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

13 comments

Comments feed for this article

May 21, 2008 at 3:59 am

tero

Mary, thanks again! Do you know anyone who would’ve seen that first edition of Crowley-Harris deck..? Wonder what their (A.C. & F.H) thoughts were on hearing news about “brown Thoth” being printed..

-tero

May 21, 2008 at 6:00 am

marygreer

Tero – I’ve never seen a brown Thoth but, when I lived in London, met people who had either seen or owned one. I’m sure Frieda Harris was very disappointed in the result. I had the book for a couple of years before I managed to find a deck for sale. Boy, was that frustrating!

May 27, 2008 at 1:25 am

Shawn

A fantastic read! I’d love to know how you define/distinguish “modern” Tarot from it’s ancestry.

May 27, 2008 at 12:40 pm

Stephen

In my humble opinion I would have put “modern tarot ” renaissance as a part of the age of enlightenment… say late 1700’s onward to the 1920’s..(Etteilla, Gebelin,Levi,Crowly and Case) and building up to A E Waite’s pivotal anglo-american deck. The rediscovery in the very late 60’s or very early 70’s and “new age movement” does count as a renaissance too but it was the second flowering of the earlier true renaissance of tarot. Then we have the Third commercial driven renaissance of the 80’s ands the tarot deck explosion. Still certainly you nailed the 20th century tarots true and best renaissance of that period. How did you decide on the 20th century as “modern”?

May 28, 2008 at 10:51 am

marygreer

Shawn & Stephen – see my blog entry where I addressed your excellent points.

August 15, 2009 at 10:24 am

mkg

A further note on “modern.” Historians label the “modern” period as beginning with the Italian Renaissance and printing (the mid-15th century) or the Enlightenment & Revolutionary periods (centering around the 1780s) which puts the original decks right in the middle of these transitions into the modern world.

I come from a background in English literature, rather than history background where the modern period begins as far back as William Blake (late 18th century) or as far forwards as W. B. Yeats (late 19th & early 20th centuries).

It’s interesting that all of these period markers exquisitely frame each stage of the major developments of the tarot. By “modern” I intended to speak of the most recent surge of tarot activity within the memories and experience of a large number of people yet alive.

Also, although “renaissance” can mean any kind of renewed interest, it also suggests a period during which the renewal spreads throughout the broader culture, effecting the entire art and ideas of the time. Tarot could certainly be said to do this from the late 1960s onward, whereas interest in the 1850s and fin de siecle was more limited in scope.

February 20, 2010 at 4:25 pm

William Haigwood

Mary–

This is an excellent history of the steps taken that brought into view documents and readings re: the Tarot. As a young member of the Counterculture, though, I cannot overstate the impact of New Age thinking and living on the resurgence of interest in Tarot and other synchronous systems (astrology, I Ching, etc). These gathered at a vortex of new ideas that focused generally on personal fulfillment and transpersonal experience and that sought to incorporate very personal scripts into contexts of human existence. At the political and cultural levels, these translated into support for civil rights, sexual freedom, experiments in communal living, and a personal non-conformity that celebrated the inherent right to “do one’s own thing…” At a personal and spiritual level this manifested as interest in a higher consciousness (sometimes with the assistance of psychogenic drugs), a profound new body awareness (healthy, natural foods and simple living), and a belief in an individual’s unique “path” shaped by much more than what was made visible by genetics or psychology. Synchronous systems became at first a popular divinatory tool for projection of personal archetypes but, as this experience became more understood, Tarot especially offered symbolic (and artistically beautiful) reflections of these archetypes that bolstered personal mythologies of conscious identity. This takes us forward to the popularization of Joseph Campbell’s writings on a hero’s journey, Jung’s resurgence and a new interest in a collective unconscious, and (in 1969) our first photograph of the entire planet Earth from space–an image plastered on the cover of the first Whole Earth Catalogue with publisher Stewart Brand’s iconic quote: “We’re as Gods and we might as well get good at it.” As well, the stunning color and deliciously arcane style of the Rider-Waite deck especially, was a retro visual feast. Large posters of the Sun and Hanged Man cards (notably) hung comfortably next to the psychedelic art just finding its way into view. And Tarot has grown up with many of us and aged very well, offering as it does an infinite mirror for the reflection of our cycling, oscillating lives…

February 20, 2010 at 4:54 pm

mkg

William –

You failed to mention your incredible Counterculture Tarot, so I’ll do it for you.

Everyone, checkout this deck consisting of photographs from the ’60s and early ’70s by photojournalist, William Haigwood:

http://www.counterculturecreations.com/card00.html

I really like your comments about the intersection of the personal and what I’ll call cosmological—a Renaissance term (you said transpersonal). Campbell and Jung were the major impetus to my interest in tarot in 1967 and I hung a huge poster of the Fool card in my office in 1973.

I find that tarot appears somewhere in most commentaries on the period. It represents a desire eschew “normal” channels to tap into both a random and divine (which are not necessarily different) cosmos for inspiration and life direction.

February 20, 2010 at 5:03 pm

William Haigwood

Thanks, Mary. That’s much appreciated. And I’d forgotten the Fool card poster–another icon of the period that showed up in lots of different places. I work in Social Services and, increasingly, I see therapists turn to symbolic systems like the Tarot and astrology (Liz Greene has written extensively about this) to assist in tapping, as you say, “into the random and divine.”

January 26, 2014 at 3:50 pm

Paul Nagy

Take a look at the historic occurrences of the word “tarot” in English over the last 200 years in google’s ngram viewer: These occurrences are inclusive of all books and periodicals scanned and indexed by Google

What do you think the blips mean?

https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=tarot&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=1&share&direct_url=t1%3B%2Ctarot%3B%2Cc0

October 22, 2020 at 1:27 pm

Pete Coe

Hi Mary

We shared readings at Readers awhile back, I saw a Tarot Deck in a book shop or pawn store in NYC in 1969 I still have it qithout the box and missing 3 cards and had to have it. Little did I know that Tarot was how I was going to spend my retirement.

Love

Pete

February 23, 2023 at 4:29 pm

Taryn

Another minor text to mention is Leo Martello’s 1974 “Secrets of Ancient Witchcraft: With the Witches’ Tarot,” which includes reproductions of a crude deck that supposedly was circulated in some Wiccan groups at the time.

I have the Basil Rakoczi book, “Painted Caravan”–it is odd. And I recently acquired a hb of Papus–also odd, IMHO.

February 27, 2023 at 6:48 pm

Mary K. Greer

Taryn,

Thank you for that mention. I’ll have to look it up. I think I have a different book by Martello.

Mary