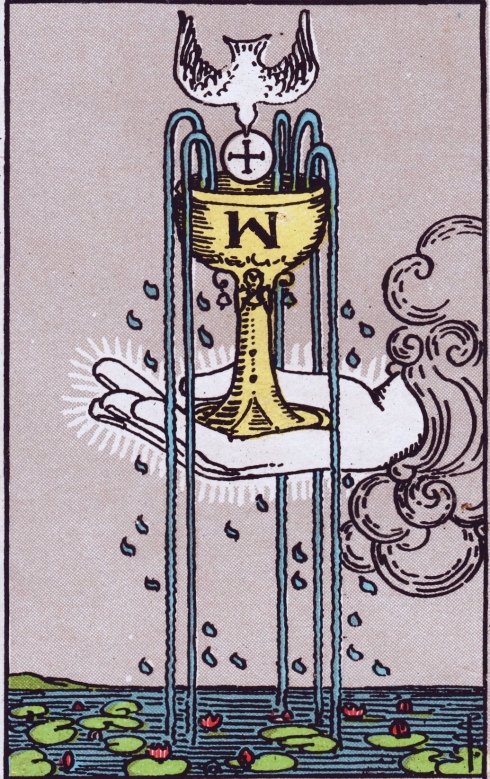

The Waite-Smith Ace of Cups, despite its seeming simplicity, is a very complex card with deep allusions that are central to Waite’s “Secret Tradition”—his mystical philosophy. This post explores Waite’s own very conscious and specific intention for this card.

As an Ace in tarot readings it generally represents an opening of the heart, new love and relationships, the emergence of psychic abilities, dreams and imagination, spiritual nourishment and the gift of grace. It is the root of empathy.

In Pictorial Key to the Tarot, Waite explains that the Ace of Cups “is an intimation of that which may lie behind the Lesser Arcana.” In other words, it is key to the whole Minor Arcana. His declaration is not really surprising as 1909 saw not only the first publication of the tarot deck but also of Waite’s book The Hidden Church of the Holy Graal (HCHG), which in over 700 pages analyzed all that was known of the Grail and its myths. Most of the quotes below are from this book unless otherwise noted. As Waite’s sentences are quite obtuse and complex, I’ve simplified where necessary.

Waite completely ignores the Greater Arcana of the Tarot in HCHG but focuses a chapter on the Lesser Arcana suits. He saw them as a reflection of the four Grail Hallows and the four treasures of Celtic lore (an idea that Yeats later passed on to Jessie Weston; see From Ritual to Romance).

“The four Hallows are therefore the Cup, the Lance, the Sword and the Dish, Paten or Patella–these four, and the greatest of these is the Cup. As regards this Hallow-in-chief, of two things one: either the Graal Vessel contained the most sacred of all relics in Christendom, or it contained the Secret Mystery of the Eucharist.”

Waite wrote regarding these Lesser Hallows,

“The Lance renewed the Graal in some of the legends [he then compares Galahad, Perceval, Lancelot, Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, Glastonbury and more], . . . but the places of the Hallows are in certain symbolical worlds which are known to the Secret Tradition. The Dish, which, as I have said, signifies little in the romances, has, for the above reason, aspects of importance in the Tarot.” [I assume here that he equates the symbology of the Dish with the tarot suit of Pentacles/Disks.]

If we need even further proof that Waite intended the Ace of Cups to represent the Grail, it is found in Waite’s divinatory meanings for the Ace of Cups, which are: “House of the true heart, joy, content, abode, nourishment, abundance, fertility; Holy Table, felicity hereof.”

He uses the term ‘Holy Table’ once in HCHG regarding an early Grail myth, describing “the graces and favors of the Holy Table” upon which the Grail appears and feeds the faithful, bringing them joy and contentment. Waite also includes this phrase in his digest of the writings of Eliphas Lévi, The Mysteries of Magic, where Lévi explains that primitive Christians gathered around the Holy Table to communicate with God and behold his face.

Although often couched in the terminology of the Catholic Church, Waite did not believe in the efficacy of instituted religions nor their requirements for ordination:

“The Mystic Quest is the highest of all adventures. . . . It exhibits the priesthood which comes rather by inward grace than by apostolical succession.”

“The Mass of the Graal . . . is celebrated only in the Secret Church and that Church is within. When the priest enters the Sanctuary he returns into himself by contemplation and approaches the altar which is within. . . . The Lord Christ comes down and communicates to him in the heart.”

When “grace and power fills them, permeates and overflows in the recipient’s heart . . . the Mystic Marriage by a Eucharistic rite” can take place—a theme central to most of Waite’s books. At heart this is a sexual mystery of Spirit and Nature, a “polarization of elements,” through which “Divine Life assumed the veils of flesh and blood” and through which flesh returns to Spirit.

This is the essence of Waite’s Secret Tradition that he wrote about in more than a hundred books and articles. He called the communication (or communion) the Eucharist, which is epitomized by the mystery of the transubstantiation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ.

In The Book of the Holy Graal, Waite explained:

The Hidden Church has sent out messengers with rumors of a noumenal Eucharist. . . . But once, through legend and through high romance, the Secret Church sent out the Holy Graal.

The secret to reading Waite is that he used words very precisely. The word noumenal is more from Plato than Kant, as it refers to objects of the highest knowledge: truths and values that exist outside of our human senses and perception. According to Waite, the Grail stories intimate or hint at the possibility of a spiritual communion with the Divine.

“The message of the Secret Tradition in the Christian Graal mystery is this: The Cup corresponds to spiritual life. It receives the graces from above and communicates them to that which is below. The equivalent happens in the supernatural Eucharist, the world of unmanifest adeptship, attained by sanctity [Grace].”

“The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ?” 1 Corinthians 10:16

Here Waite speaks more of the Eucharist, first as a higher kind of love, symbolized by the Grail, and then of the loss of “Mystery” to the world:

“The Eucharist is a mystery of the soul’s love. . . . The sense is that love is set free from the impetuosity and violence of passion and has become a constant and incorruptible flame.”

“The Holy Graal . . . is a mystery of the Eucharist in its essence. . . . It is an inward mystery [not found in the official Church]. It died, however, in the consciousness except of a few faithful witnesses, . . . [because when Christ] incarnated, a manifestation of the God within was intended but it did not take place because the world was not worthy, the Graal was said to be removed.”

As Waite saw it, our ability to directly commune with the Divine has been lost. All the official sanctuaries “are in widowhood and desolation,” even though they are “filled with meaning and intimations of meaning.” That is, they give intimations or hints of the mystical journey, which is not available in institutions as it can only be experienced within each individual. The four suits of the Lesser Arcana tell four stories of this loss.

“It must be admitted that the Lesser Chronicles are in some sense a failure; they seem to hold up only an imperfect and partial glass of vision. But they are full testimony to the secrecy of the whole experiment; they are also the most wonderful cycle by way of intimation. Their especial key-phrase is my oft-quoted exeunt in mysterium [“they exit into mystery”].”

“The sources all say the same things differently: “The Holy Sepulcher is empty; the Tomb of C.R.C. [Christian Rosy Cross] in the House of the Holy Spirit is sealed up; the Word of Masonry is lost; the Zelator of alchemy now looks in vain for a Master. The traditional book of the Graal . . . [is] lost, . . . [as is the book] which was eaten by St. John (i.e., The Book of Revelations).”

It is left to the Greater Arcana to chart the soul’s journey along the path of restitution. But that is a separate tale.

Waite claims he wrote The Hidden Church of the Holy Grail as a text-book of a Great Initiation in that there is a secret meaning hidden in these tales of loss.

“So came into being [the Graal stories]. Whether in the normal consciousness I know not or in the subconsciousness I know not . . . that dream of theirs was of the super-concealed sanctuary behind the known and visible altar.”

They point to something that can now only be experienced by the individual in the inner sanctuary of his or her own heart. “Their maxim is that God is within.”

“The history of the Holy Graal becomes the soul’s history, moving through a profound symbolism of inward being, wherein we follow as we can, but the vistas are prolonged for ever, and it well seems that there is neither a beginning to the story nor a descried ending.”

Part 2 explores Waite’s clearly intended and most likely meanings for the specific symbols in the Ace of Cups.

Part 3 is “A Jungian Approach to the Ace of Cups”.

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

14 comments

Comments feed for this article

December 11, 2017 at 9:15 am

Sheila

It only makes sense the Heart is the entrance to the soul. In this piece it sounds similar to the stages of enlightenment, and yet I can’t explain it. Which bring me to my other thought. We don’t need a middle man to commune with the Divine, we just need to go with in.

December 12, 2017 at 1:48 am

Andreas Uzun

Thanks for this small but essential tribute to that great mystic of old. It seems that nowadays we know more about Waite’s deck than Waite himself, which is a real pity.

Let me insert here a lovely sonnet of Arthur Edward Waite, “The Invocation of the Soul”, which I find not irrelevant to our subject:

I call’d the Soul from dreamful deeps of sense

Such silence fell as when expectant Night

Feels some faint presage of approaching light

Her secret nature fill with vague suspense.

Such silence fell – then rose one spark intense

Of purest lustre, beautiful and bright,

And calmly from the intellectual height

All earthly coulds dispersed, all darkness dense.

The waxing glory of one sacred deed

That dormant Soul magnetically drew,

As two fond eyes through waters gazing down

Draw mild Undine to her lover’s view:

From depth to height, of all her bondage freed,

High aims lead on the Soul to starry crown.

December 12, 2017 at 7:56 am

Lisa Frideborg Eddy

Thanks for this, Mary. The Ace of Cups is my favourite card and the Waite Smith Ace of Cups is my favourite Ace of Cups. Look forward to reading part two.

December 12, 2017 at 9:58 am

John Sorbo

Thanks so much Mary! Wonderfully written and enlightening.

December 13, 2017 at 10:44 am

mkg

Sheila –

I so agree with you. In my next piece on the meaning of the symbols I offer an active visualization to take one into the experience.

Mary

December 13, 2017 at 10:48 am

mkg

Andreas,

Thank you so much for the poem. It really helps to understand Waite’s mystical philosophy when reading his poetry, but when you do then it becomes quite clear and beautiful and not at all vague as it first appears.

Mary

December 13, 2017 at 10:49 am

mkg

Lisa and John,

I’m glad this post speaks to you. I hope to post more later today.

Mary

December 27, 2017 at 7:23 am

wmeegan

I agree that the ACE OF CUPS symbolizes the Holy Grail; however, that as far as it goes for this post to reveal secrets about this Minor Arcana Tarot Card.

All the clues are in the card; plus, each Minor Arcana Tarot Card has to be viewed with the other pip cards with the same number.

It amazes me how much so-called experts do not reveal; though, that information is in plain sight.

December 27, 2017 at 3:42 pm

Mary Greer

wmeegan,

It’s easy to say that secrets haven’t been revealed when you don’t include any examples. I believe you failed to read the opening paragraph. This is not a post on everything about the Ace of Cups. I’ve attempted to summarize Waite’s intention for the card as expressed in his other writings on the theme—not to cover every possibility. Feel free to add to this discussion or link to a post that does.

Mary

December 27, 2017 at 6:45 pm

wmeegan

Mary Greer you did cover most of the symbols in the ACE of CUPS; but, not what it means per se.

The ACE of CUPS is the Eucharistic Chalice and the pouring of the content of the cup down to the earth is scattering Christ: i.e. Eucharist into the outer world, which has to be gathered back together again in order for the initiate to return with the Holy Grail. I wrote a brief paper on the Minor Arcana Tarot Cards https://www.slideshare.net/williamjohnmeegan/riderwaites-major-and-minor-arcana-tarot-cards-reveals-the-secrets-of-the-esoteric-science I recommend that you read it. It is not everything; but, it is briefly showing how to read the cards.

As you will see I positioned all four Aces with the associate Eights; because, the number nine creates the Sun Signs of Astrology: i.e. 1 & 8 (Mars), 2 & 7 (Venus), 3 & 6 (Mercury) and 4 & 5 (Moon and Sun). ttps://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1608839325822142&set=pcb.1607711535934921&type=3&theater this link will give you a quick look at what I am talking about in the paper. You should look studiously at the Cups (1 & 8), Swords (1 & 8) and Pentacles (1 & 8) you’ll see that the pattern is transformed in to 1+3+5, which are the numerics for the Vesica Piscis (153). I can’t go writing a book here; but, I wrote another paper (PRECESSION OF THE EQUINOXES: How the Ancient Astrologers learned of it) showing how spirituality exist outside the time/space continuum and I show where I got my mathematical evidence https://www.slideshare.net/williamjohnmeegan/precession-of-the-equinoxes-how-did-ancient-astrologers-learn-of-it

The ACE of CUPS scattering the Eucharist (Christ) into the world as depicted in that card show 13-leaves in the water and 10-roses. Thirteen is the Gematria value of the number one (MONAD: i.e. God): ALEPH (Elohym) and ten symbolizes YUD (Yahweh); thus, developing the Trinitarian Paradigm (Trinity). YAHWEH four letters creates the letter ALEPHS where one Yud stays in the spiritual realm and the other is scattered into the world via the four elements: Wands (Fire), Cups (Water), Swords (Air) and Pentacles (Earth). All of this is esoterically laid out in the first chapter of Genesis.

The Cross in the Wafer Host symbolizes the CROSSING in the Church, which symbolizes the center of the SKULL. In the Church the railing is along the transept and at the CROSSING is where the Eucharist is delivered (scattered) to the laity. The CROSSING actually symbolizes the Pineal Gland from which spirituality emanates. That is why on a esoteric symbolic level the altar area (apse) does not exist. There is a great deal more; but, I will stop here.

January 4, 2018 at 10:42 am

mkg

wmeegan,

I still don’t think you’ve heard the intention of my post. It is to elucidate Waite’s probable intention for the card, based on what he said about the symbols and theme of the Grail in Waite’s own writings. I looked at your article but did not see a direct connection to Waite’s ideas, despite your claims, largely because you use a vocabulary that is entirely different from his. If you quoted from Waite or the Golden Dawn to substantiate the association it would become clearer how your theory is related to their teachings.

I don’t know what Waite was thinking other than what he wrote. I believe Tarot can be viewed from myriad other perspectives—we don’t have to agree with Waite or take his view as the only valid one. I agree with you that this one card in itself does not tell the whole story. I also don’t think the Tarot itself tells just ONE story. It’s wonderful that you’ve found an understanding that works so well for you.

Mary

January 4, 2018 at 6:03 pm

wmeegan

Mary:

I believe that the Golden Dawn was introducing the understanding of symbolism and their esoteric secrets to its initiates via multiple Tarot Card decks. As some of its members have said you cannot understand esotericism unless symbolism is understood.

I see the Tarot Cards as emphasizing the Hebraic Alphabet, which is the only true way for the Western Culture to understand esotericism. This does not mean that comparative religions cannot also be helpful illustrating all religions teach the same esotericism; but, such comparative religion research cannot be as helpful as the initiate’s religion.

I am only beginning to realize that after 43-years of research I have looked only at the tip of the iceberg. I have a many books on the Hebrew alphabet and also many on the Tarot Cards. It will be in researching these tools that I believe will allow me to go deeper into the submerged iceberg that is only visible to the third eye.

Your revealing Arthur Edward Waite’s second deck of Tarot Cards has illustrated to me why Judaism does not believe in images. It has always perplexed me over the span of my life as to why Judaism negated images.

Christianity symbolizes images and Judaism symbolizes the Logos. It is both images and Words (word and image) together that creates the third eye.

This does not mean compromise or amalgamation; rather, it means seeing what words and images independently mean. That is why the Hebrew Coder is symbolically and alphanumerically coded.

I am still waiting for that book to come across the pond: i.e. Great Britain to the USA.

January 22, 2024 at 3:35 am

聖杯王牌的象徵意義 | 安蘭老師靈魂占星學

[…] 韋特史密斯的聖杯王牌形象並不是獨一無二的。在維斯康提-斯福爾扎卡中,一個長著翅膀的人物站在噴泉上,從噴泉中流出水。在馬賽牌中,兩張王牌(權杖和劍)有一隻從雲中伸出的手——這是一種標準的中世紀裝置,表示來自神聖來源的創造、奇蹟和禮物。我們在上面的圖片中也發現了相似之處。第一個來自威廉·豪斯柴爾德 (Wilhelm Hauschild) 的聖杯聖殿 (1878 年) ,第三個是 羅赫里奧·埃古斯奎扎(Rogelio Egusquiza) 的《桑托·格里亞爾》( Santo Griaal )(1901 年由大英博物館收購)。順便說一句,如果你像我一樣是異教徒,我鼓勵你將基督教的參考文獻視為心理隱喻。請在此處閱讀第 1 部分。 […]

January 22, 2024 at 7:45 pm

Mary K. Greer

You are so right that the Waite/Smith Ace of Cups is not unique! A comparative article would point out the classical similarities as well as the differences among decks like the ones mentioned in your comment.