You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Story in a Picture’ category.

Several people have been blogging about their experiences as they go through my book 21 Ways to Read a Tarot Card. It’s a great way to share your insights and get feedback from others. Personally, I was delighted by the story resulting from Step 4 as recounted by “Tarot Dude” (Roger Hyttinen) on his blog—read it here. Using The Gaian Tarot‘s Seeker [Fool] card, Roger began with a fantasy tale about a young woman named Sally who went to work every day in a cubicle. But, in the second part of the exercise, when it came time to retell the story in the first person/present tense, the story became very personal:

My name is Roger and I go to work every day to a cubicle. Oh, I had planned on going to college, but things just didn’t work out the way I had anticipated. A bad breakup and the lack of my parents’ ability to provide any financial assistance forced me to take an office job performing menial tasks. “It’s only for awhile, it’s only temporary,” I tell myself.

But my heart aches. I feel out of sorts with the rhythm of life. I have the strongest feeling that I am not doing what I was put on earth to do. I really can’t explain it – but everything just feels wrong about my life. . . .

The story continues with the appearance of a little red fox who tells him about dangers to the world and eventually asks if Roger will accept going on a journey:

“Journey? What journey? I just can’t pick up and leave. I’ll have to pack. I’ll have to tell my family that I’ll be leaving. So many things to do.”

“Impossible,” says the fox. “Time is of the essence.” He nods toward a tree. “Behind that tree is a small blue bag that contains all you will need. Mama Gaia will provide the rest. You need to have faith that all will work out. You need to know that you are following your destiny – and your destiny, my little man, is to save the world.” The fox pauses. There is sadness in his eyes. “Please, do not let fear prevent you from taking this journey. For if you do not accompany me right now, then all is lost.”

I stare at him but say nothing. I wring my hands together and look off into the distance, trying to decide what to do.

“So,” says the fox. “Do you accept?”

I take a deep breath and nod. “I accept.”

“Well then, let us not tarry. Our journey begins now.”

When you realize it really is about you, such a story can have a deeply transformative effect (I encourage you to read the whole thing). Since Roger really did go to college, the first part of the story is a metaphor asking, basically, what everyday, menial tasks are currently constraining him from addressing the “big” (college-level) questions and issues in life?

Check out Roger’s other posts at Tarot Dude.

Let me know if you are blogging about 21 Ways to Read a Tarot Card and I’ll add your link to this post. Also, let me know if you’ve written a review of my book (laudatory or critical) and I’ll also link to it.

Blogging 21 Ways to Read a Tarot Card

- Tarot Dude

- Zorian’s Tarot Quest – the posts for each Step are well organized in their own section of the blog.

- Aeclectic Tarot Forum’s Study Group for 21 Ways to Read a Tarot Card (not actually a blog)

Reviews

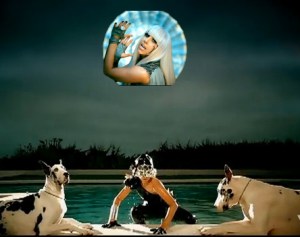

Some people say there’s a lot of tarot symbolism in Lady Gaga’s music videos (see also here and here). Send me stills that clearly were intended to depict specific tarot cards, and I’ll post them. For instance, here’s The Moon card from “Poker Face”—made all the more explicit by the images juxtaposed with each other in the video. To me, it represents the femme fatale, at her most instinctive, climbing up out of the pool of the archetypal collective unconscious.  A later image with just one dog could be Strength. At the end of the video we see The Sun card (sunrise after a night playing strip poker), complete with two children frolicking in front of a wall. It represents the success of the sexual seduction gambit that is spelled out in the lyrics, but also a kind of return to innocence (white clothes and gloves instead of the black).

A later image with just one dog could be Strength. At the end of the video we see The Sun card (sunrise after a night playing strip poker), complete with two children frolicking in front of a wall. It represents the success of the sexual seduction gambit that is spelled out in the lyrics, but also a kind of return to innocence (white clothes and gloves instead of the black).

You can see a large image of this painting in my earlier post, along with an in depth discussion in the comments section.

Here’s an alternate version of this video:

Saltimbanques-1 (note: turn down your volume control first).

I uploaded this animoto video to youtube in Hi-Res. Try watching it full-screen! Please share it around.

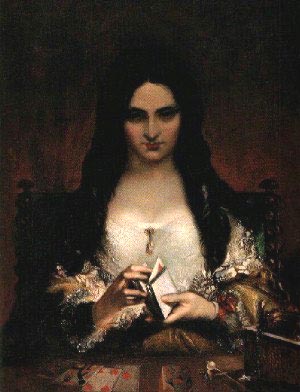

What story does this painting tell?

and here’s a couple more:

What’s a Man Gotta Do – Die Kartenslaegerin

What’s a Man Gotta Do – Die Kartenslaegerin

J-G Vibert – Tireuse de Cartes (The 5th)

J-G Vibert – Tireuse de Cartes (Smoke & Mirrors)

which of the two Vibert videos do you like better?

(Click here to get $5 off a year’s Animoto All Access Subscription (= $25) or use the code ptcsgdhi )

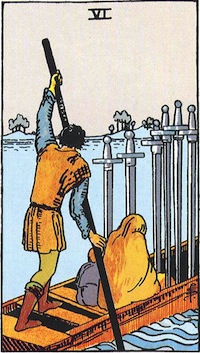

Few things are more exciting to me than stumbling across a text or image that perfectly reflects a tarot card, especially when it makes me reconsider my ideas about that card.

Today I read the following in the mystery novel A Rule Against Murder by Louise Penny. Chief Inspector Armand Gamache, head of homicide for the Sûreté du Québec, says to a family at their annual reunion:

“We believe Madame Martin was murdered.”

There was a stunned silence. He’d seen that transition almost every day of his working life. He often felt like a ferryman, taking men and women from one shore to another. From the rugged, though familiar, terrain of grief and shock into a netherworld visited by a blessed few. To a shore where men killed each other on purpose.

They’d all seen it from a safe distance, on television, in the papers. They’d all known it existed, this other world. Now they were in it. . . .

No place was safe.

Ah, a perfect rendition of the Six of Swords! I was first struck by it being from the viewpoint of the ferryman, not the passengers. A ferryman who is compassionately aware of the deep emotional shifts of those he is transporting—but not partaking directly in those shifts. For a moment I thought, ‘But, of course, the Six of Swords is about the ferryman, not necessarily the passengers! A ferryman who again and again observes this shift taking place in those he ferries. A ferryman who is both separate and yet momentarily involved.’

Ah, a perfect rendition of the Six of Swords! I was first struck by it being from the viewpoint of the ferryman, not the passengers. A ferryman who is compassionately aware of the deep emotional shifts of those he is transporting—but not partaking directly in those shifts. For a moment I thought, ‘But, of course, the Six of Swords is about the ferryman, not necessarily the passengers! A ferryman who again and again observes this shift taking place in those he ferries. A ferryman who is both separate and yet momentarily involved.’

There is no indication that the author, Louise Penny, had the tarot card in mind. Rather this is a common classical metaphor linking Charon and the river Styx to the family of a murdered person being ferried out of the world-as-they-had-known-it to a shore previously viewed only as a distant abstraction.

I often ask a querent, “Where are you in the card?” With the Six of Swords, the querent is always one of the figures, but it could equally be the ferryman or the hunched-over adult or the child. By contrast, with other cards, the querent occasionally sees him or herself standing just beyond the borders, behind a column, or, in the case of the Tower, still inside the structure—divorced from the action.

With the Six of Swords there is usually an eventual recognition that the querent is all three persons in the boat. As ferryman, the querent tends to feel he or she is in charge or at least doing something active that will lead to a better end. As passengers, anxiety or grief tends to trump hope, yet there is still a belief that the destination will be better than the “familiar terrain of grief and shock” that they’ve just left.

Interestingly, in the novel, the seven main suspects had, just the day before, gone out together in the lake on a boat—a passage fraught with animosity and repressed danger. The Chief Inspector/ferryman recognizes that the new world they are now facing will be more terrifying than the passengers ever could have imagined. Furthermore, they aren’t just visitors—blessed because they can leave—they will soon be inhabitants. There’s no going back. Grief and shock may exist in the land of the innocent. But, in the land of the experienced, as William Blake well knew, wrath and fear dominate, and the ferryman can’t stop it from happening. (See Blake’s Poems of Innocence and Poems of Experience.)

How different the card looks to me now. It is full of foreboding, and yet there is calm in knowing that this is an inevitable journey from the false safety of innocence into the land of Blake’s experience where realities will finally be faced. As in all murder mysteries the truth will be revealed. But, in an actual reading, is the client always ready to hear such truths?

Doesn’t the admonition, “to know thyself,” mean that we have to come to know and take responsibility for the part within ourselves who “kills another”? Both the querent and the reader want the other shore to be better than the one from which they’ve come, but there are times when we have to go through much worse. What is the reader to tell the client? And, here there are no easy answers.

I hope this makes me stop and think before I blurt out cheerfully, “Oh, you are going through a transition from the rough waters of the past to smooth waters ahead.” Sometimes I, the reader, am the ferryman/chief inspector, who must recognize with compassion that real detection can strip the soul bare and set one in the dread grasp of Blake’s tyger and not in the rejoicing vales of the lamb (see poems here). The rest of the Sword suit (7–10) warns what may come from a detection of the wrongs, or what comes to light when one really wants to “know thyself.” Does the querent really want to go there, or is the querent trusting the reader to ferry them to a safe harbor?

Still, I think it helps the reader—the ferryman who steers the way through the cards in a spread from one’s familiar anxieties to a different shore—to consider what may be truly implied from such a scene in the suit of Swords. This new perspective reminds me that in a reading I am attempting to steer the course when I don’t always know what is lying in wait for my passenger on the other side or how prepared my passenger might be to meet that. It is a grave responsibility.

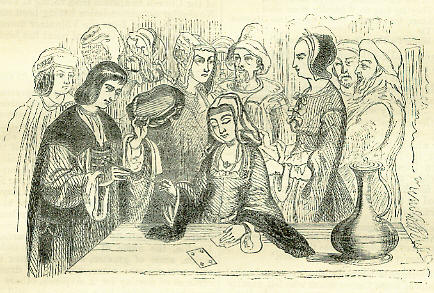

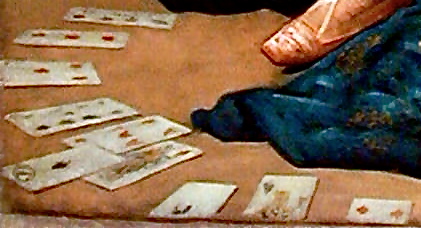

No one knows the story behind the painting “The Fortune-Teller” by Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), so it is ripe for speculation. It was painted in 1508 when Lucas was only fourteen, marking him as one of the great painters of the age. This work is also considered to be the first “genre painting” that depicts everyday events in ordinary life. If what is shown is truly fortune-telling with cards then it is one of the earliest records of cards being used in this way (see Origins of Playing Card Divination).

I believe the cards in this picture represent the many turns of fortune, but it may be more of a metaphor than an actual card reading. Still, we know from research by Ross Caldwell that by 1450 playing cards were used in Spain for fortune-telling “puédense echar suertes en ellos á quién más ama cada uno, e á quién quiere más et por otras muchas et diversas maneras (“one can cast lots [tell fortunes] with them to know who each one loves most and who is most desired and by many other and diverse ways.”) And, as we will see, both of the main characters in the painting married into the Spanish royal family and spent time there.

The central woman is thought by some to be Margarethe (Margaret) of Austria and Savoy (1480-1530) (see also here). Born in Flanders, she was daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I and Mary, Duchess of Burgundy. Her step-mother was Bianca Maria Sforza, daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, by his second wife, Bona of Savoy, and granddaughter of Bianca Maria Visconti (m. Francesco Sforza) for whom the Visconti-Sforza Tarot was made.

At three years of age Margarethe was betrothed to the Dauphin of France (later, Charles VIII), but at ten was returned to her family when he married someone else. In 1497, at seventeen, she and her brother, Philip ‘the Handsome’ (Archduke of Austria, ruler of Burgundy and the Netherlands, and in line to become Holy Roman Emperor), were married off in a double alliance to the Infante Juan and Infanta Juana, children of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile (who sent Columbus to America). (Pictures below are of Philip and Margarethe.)

The Infante Juan died six months later and Margarethe’s child was stillborn. Margarethe was then married to Philibert (Phillip) of Savoy with whom she was very happy, but he died three years later. (He, by the way, actively supported the Milanese cause of the Sforzas against the French until offered a bribe by the French that he couldn’t refuse.) So, by the age of twenty-four she had already had a betrothal broken by France’s Charles VIII, lost a child, and was the widow of both the Infante Juan of Spain as well as of her much loved Philibert. Although her family tried to entice her into a marriage with Henry VII of England, she vowed never to remarry and took the motto: FORTUNE . INFORTUNE . FORT.UNE that has been translated as “Fortune, misfortune, and one strong to meet them.” I see it as both a reminder of her sad story and her claiming of the strength (forte) that such adversity had brought her.

Meanwhile, in 1506, Margarethe’s beloved brother, Philip the Handsome, was named King of Spain, but he died that same year, his son becoming the next King of Spain (Carlos I) and eventually Holy Roman Emperor (Charles V). In 1507 Margarethe was named governor of the Habsburg Netherlands, in place of her brother, and guardian of his seven-year-old son. She went on to become a significant political figure and patron of the arts, negotiating treaties and continuing to rule the Netherlands at the behest of her father, Maximilian, and then her nephew.

There is a possibility that Lucas van Leyden’s 1508 painting commemorates Margarethe of Austria’s ascendancy to the governorship of the Netherlands in 1507, following the death of her brother, Philip the Handsome. The flower being exchanged (a “pink” signifying loyalty in love?) could represent the passing on of the governorship and their love for the people of the Netherlands who could be the commoners pictured in the background witnessing the change-over. The daisy on the woman’s gown could be meant to identify her (a marguerite daisy). Philip the Handsome (portrait above left) wears a necklace and hat similar to those in “The Fortune Teller” where his doffed hat and sad eyes seem to illustrate his mortal leave-taking. The portrait on the right shows Margarethe in widow’s garb as she liked to be seen in the second half of her life. The Fool with his bauble (fool’s sceptre) may have been someone specific at the court or he may be a symbolic reminder of the foolishness of thinking that a high place and worldly honors will last. More people look at him than at anyone else. There are clearly three layers to the cards: Philip & Margarethe, the Fool and a lady-in-waiting(?), and a backdrop of commoners who may represent the people of the country who are unsure what is to become of them.

At least one other painting by van Leyden is said to show Margarethe’s involvement in political negotiations pictured as a card game (1525; see below). It is thought to refer to a agreement between Emperor Charles V (left) and Cardinal Wolsey (right) to form a secret alliance between Spain and England against Francis I of France. Margarethe is known to have been involved in these negotiations. This painting would therefore refer back to the 1508 one where her position as regent of the Netherlands was commemorated.

A nineteenth century etching based on the painting (the etching is from Le Magasin pittoresque, 1840) was identified as “The Archduke of Austria Consulting a Fortune-Teller” when reproduced in Chambers‘ article on card reading. It has often been depicted as proof of early playing card divination. As we’ve seen, that may be too simplistic a view. However it is interesting that Philip the Handsome was Archduke of Austria (and his sister became Archduchess of Austria after him).

Here’s a couple more portraits of Margarethe. The one on the right has a similar neckline to the one in our painting (though slightly higher):

Here’s a couple more portraits of Margarethe. The one on the right has a similar neckline to the one in our painting (though slightly higher):

.

.

.

.

[Special thanks to Huck Meyer, Rosanne, and Alexandra Nagel—all who offered pieces of the puzzle.]

Here’s a second painting that clearly tells a story (see the earlier Dorés’ Saltimbanques). This picture is by the Flemish painter Nicolas Régnier (1591?-1667), a contemporary of Caravaggio, who spent most of his life in Italy. Many of Régnier’s paintings show the seamier or more frivolous side of life and several feature gypsies. One commentator characterized his work as expressing a “poetics of seduction.” This painting from around 1620 has variously been entitled Kartenspielende Gesellschaft and The Cardplayers and the Fortune-Teller. Use the Comments to tell us what story (or stories!) you see in this picture. What relationship might the artist be implying between cards and palm reading? What do each of these nine people want? Click on the image to see a larger version. Have fun.

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Recent Comments