You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Tarot History & Research’ category.

I’m back from New York and will be starting up the Tarot posts again soon. In the meantime, here’s a link to a translation by Donald Tyson of Antoine Court de Gébelin’s essay on the Tarot that started the whole occult tarot lineage and the belief in its Egyptian origin. It is followed by an essay by Le Comte de M*** (Mellet) on reading the cards that also appeared in 1781 in Vol. 8 of de Gébelin’s encyclopedic work Le Monde Primitif. These seminal works should be read by everyone who has any interest in tarot history. Try out the first published tarot spread from Le Comte de Mellet’s essay here.

See this blog article on the marginalia of U.S. President John Adams that includes comments on three volumes of de Gébelin’s encyclopedia, including this: “What a coruscation of metaphors, fables, allegories, fictions, mysteries and whatnot!”

Read a biography of Antoine Court de Gébelin from LE TAROT Associazione Culturale.

Are we tarot readers in the business of predicting the future? Some readers claim they are. They explain that we may be no more accurate or inaccurate then weather forecasters and stock market analysts (surely more accurate than stock market forecasters!). Of course, this hasn’t been formally tested yet. So it might behoove us to get a little understanding of the overall field of forecasting. For instance, the International Institute of Forecasters at the Wharton Business School, University of Pennsylvania has been developing theories, as well as testing and comparing different methods. Here’s how they define forecasting:

“Estimating in unknown situations. Predicting is a more general term and connotes estimating for any time series, cross-sectional, or longitudinal data. Forecasting is commonly used when discussing time series.”

So far tarot readings haven’t made the grade for their studies or even their listing tarot readings among the possible methods. Why should we be left out?

And here’s some information from the FAQ at forecastingprinciples.com:

Who can do forecasting?

“Anyone is free to practice forecasting for most products and in most countries. This has not always been true. Societies have been suspicious of forecasters. In A.D. 357, the Roman Emperor Constantius made a law forbidding anyone from consulting a soothsayer, mathematician, or forecaster. He proclaimed “…may curiosity to foretell the future be silenced forever.”

“It is sensible for a person practicing forecasting to have been trained in the most appropriate methods for the problems they face. Expert witnesses who forecast can be expected to be examined on their familiarity with methods.”

Aren’t forecasts wrong more often than they are right?

“This is a trick question. Some things are inherently difficult to forecast and, when forecasting numerical quantities, forecasters can seldom be exactly right. To be useful, a method must provide forecasts that are more accurate than chance. This condition can often be met, but one should not assume that it will be. A good forecasting procedure is one that is better than other reasonable alternatives.”

You might want to check where you think tarot belongs on the Methodology Tree.

Is it time that we begin to demand our place in the growing formal field of forecasting? Or, not?

A couple of people have asked me how I defined “modern” in my post on the 1969 Tarot Renaissance. Stephen wrote in the comments: “In my humble opinion I would have put “modern tarot” renaissance as a part of the age of enlightenment… say late 1700’s onward to the 1920’s…(Etteilla, Gebelin, Levi, Crowley and Case) and building up to A E Waite’s pivotal anglo-american deck.” And Shawn said, “I’d love to know how you define/distinguish “modern” Tarot from it’s ancestry.”

I tend to think of modern as being within the last hundred years or so – within the memory of those who are still living. I’m aware there is one school of thought that puts anything since the “Middle Ages” into the modern category—but a 600-year span makes the term practically meaningless. I suppose a better term would have been “contemporary,” although we’re almost 40 years past that.

I could say that 1969 marks the 20th-to-early-21st century Tarot Renaissance. And, that it’s defined by a continuing growth and development of tarot involving the creativity of many people, deck sales in the millions, and broadly affecting the culture in many countries around the globe. To me a “renaissance” is a creative force in the culture as a whole—affecting a multitude of cultural forms.

Can anyone point to a single year prior to 1969 in which 18 to 20 new tarot decks and/or books were produced—or even half that? Or, how about a span of many years in which an average of a dozen or more tarot works came out every single year as they did from 1969 on?

Prior to the 1960s, the best we can find is one new tarot work every few years or even decades, with the exception of 1888-89 when there were three works in two years, and the mid-1940s when three or four works were produced over several years but with very few in the decade prior to or after that.

Certainly 1781 (the birth of the occult tarot), 1854, 1870, 1888/9, 1909 and 1945 are hugely significant dates and turning points in tarot history, but these are the works of individuals in single years, not mass-movements. They didn’t directly affect the creative output of a large segment of the culture until we come to the 60s and especially 1969, when there was a popular groundswell that has continued to grow and spread.

There were around twelve new works in 1970, fourteen in 1971, nine or ten each from 1972 to ’74, seventeen in 1975, and so on. The effects could be seen throughout the culture: in poetry, painting, collage, sculpture and art installations, movies, television, theatre, fiction, comics, psychology, and even fabric, clothing and jewelry design.

Something happened to tarot since the late 60s and 70s that is vastly different and more creative then anything that had happened before, and across a much wider range of human experience.

I may not have all my terms right, but I’m trying to get some understanding of what happened. Keep the comments coming.

Like getting your history from a visual medium? Here’s one of the best brief video overviews of early tarot history out there, despite the incorrect prounciation of the Italian (not French) word tarocchi (correct: “tah-ROH-key”)—plural form of one of the oldest names for the cards, which is still used in Italy. However, when it comes to the later occult and divinatory tarot, videographer Mark (tokarski21) couldn’t resist falling into the occult-as-Devil trap. This is really too bad for someone who professes to deal straight with history. Mark promises to delve more into the subject later so I hope he gets better sources (me!?) and treats the subject with more historical objectivity. Catch up with Mark’s other videos here and here.

When did the modern tarot renaissance actually begin? It’s always hard to pinpoint the beginning of a movement but here are some events worth noting that lead up to the breaking of the dam in 1969. I’m looking for corrections and additions to the information below, plus tarot stories from the 60s and early 70s. Please share them in the comments.

The 1940s saw some interesting tarot activities that set the stage for the later renaissance. The Crowley-Harris Thoth deck was completed and published in a limited edition of 200 in monochrome brown by Chiswick Press, but these were not available to the general public. In 1947 Paul Foster Case published his masterful work The Tarot: A Key to the Wisdom of the Ages, based on his tarot correspondence course. In France, Paul Marteau came out with his hugely influential book Le Tarot de Marseille that noted the symbolic significance of the smallest details in the deck. In Brazil, J. Iglesias Janeiro, published his book La Cabala de Prediccion, which popularized the turn-of-the-century Egyptianized Falconnier/Wegener cards. It became a center-piece of his important occult school, known mostly in Latin America. Meanwhile, in the U.S.A., Dr. John Dequer published The Major Arcana of the Sacred Egyptian Tarot, which was his revised version of those same Egyptianized cards, similar to what was already being used by C.C. Zain’s Brotherhood of Light correspondence school.

The Insight Institute in Surrey England started up their tarot correspondence course (later published in a book by Frank Lind) and produced their occultized version of the Marseilles deck (eventually published as the R.G. Tarot). Also appearing was an unusual book, solely on the psychological dimension of the Minor Arcana cards numbered 2-10 as they are associated with one’s birthday. It was Pursuit of Destiny by Muriel Bruce Hasbrouck, who had studied with Aleister Crowley when he was in the United States. Tudor Publishing’s The Complete Book of the Occult and Fortune Telling became the sole source in English of the unique Tarot card interpretations from Eudes Picard’s 1909 French work, Tarot.

The 1940s also saw the incorporation of Tarot imagery in surrealist artworks such as Victor Brauner’s “The Surrealist,” and in Jackson Pollack’s “Moon Woman” (both of which I happened upon when I visited the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice following the 2000 Tarot Tour with Brian Williams). William Gresham’s novel, Nightmare Alley, featured a carny mentalist who reads tarot and the book is presented as a twenty-two card reading. A year later Tyrone Power played the lead in the movie version featuring two tarot readings by Joan Blondell. Charles Williams’ landmark tarot novel, The Greater Trumps came out just as this decade ended and the next one began.

The 1950s produced even fewer tarot works. George Fathman published The Royal Road: A Study in the Egyptian Tarot, which used Dequer’s version of the Falconnier/Wegener cards. Paul Christian’s seminal work The History and Practice of Magic was translated from French to English, providing the original source material on which all those Egyptian-style decks were based. Arcanum Books reissued Papus’ The Tarot of the Bohemians with an introduction by librarian Gertrude Moakley, who noted the influence of tarot on creative writers and in psychology. Off in the Netherlands, Basil Rakoczi published the English language letterpress art book: The Painted Caravan: A Penetration into the Secrets of the Tarot Cards. Yet, the tarot seemed likely to fade away from popular view.

1960 started out the decade with a bang. University Books published Waite’s A Pictorial Key to the Tarot for an American readership, as well as a deck: Tarot Cards Designed by Pamela Colman Smith and Arthur Edward Waite. Eden Gray self-published her Tarot Revealed that still sells well to this day. In England Rolla Nordic came out with The Tarot Shows the Path: Divination through the Tarot. These last two books showed a clear shift in interest to practical tarot readings for the masses. Muriel Hasbrouck’s greatly overlooked 1940s work was re-published.

As the 60s progressed we got two heavy metaphysical works: Mouni Sadhu’s Tarot: A Contemporary Course of the Quintessence of Hermetic Occultism, and Mayananda’s The Tarot for Today, a study of Crowley’s material in the Book of Thoth (despite the latter’s being unavailable). The Brotherhood of Light came out with a new, revised edition of their 1930s Tarot deck. Idries Shah claimed, in The Sufis, that the Tarot was a Sufi creation. Influenced by T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” and Yeats’ involvement in the Golden Dawn, poets like Robert Creeley, John Weiners, Diane Wakowski, Sylvia Plath, Philip Lamantia and Diane di Prima began using tarot imagery in their poems. While not published until 1974, Jack Hurley and John Horler worked on “The New Tarot,” a Jung-based deck, at the Esalen Institute throughout the 60s, influencing many who passed through there.

In 1966 Gertrude Moakley set tarot history on it’s ear with her groundbreaking research in The Tarot Cards Painted by Bembo. The Grand Tarot Belline deck was published in Paris, as was a new edition of Oswald Wirth’s 1927 book, Le Tarot des imagiers du moyen age, that included his 22 card deck. Beginning in 1966 and running through 1971 the day-time TV soap opera Dark Shadows gave many people their first glimpse of a tarot deck as various episodes featured readings with the Marseille deck.

In 1966 Gertrude Moakley set tarot history on it’s ear with her groundbreaking research in The Tarot Cards Painted by Bembo. The Grand Tarot Belline deck was published in Paris, as was a new edition of Oswald Wirth’s 1927 book, Le Tarot des imagiers du moyen age, that included his 22 card deck. Beginning in 1966 and running through 1971 the day-time TV soap opera Dark Shadows gave many people their first glimpse of a tarot deck as various episodes featured readings with the Marseille deck.

By 1967, even a paper company jumped on the bandwagon with its advertising Linweave Tarot Pack that gave David Palladini his introduction to tarot design (see card on right). Helios Books in England published a small edition of the Golden Dawn’s Inner Order tarot teachings, Book T. Doris Chase Doane came out with two books that helped popularize the Brotherhood of Light Egyptian tarot deck in America. Sidney Bennett wrote Tarot for the Millions.

In 1968, the House of Camoin reproduced the classic 1760 Tarot de Marseille based on original pearwood woodcuts. The mysterious Frankie Albano redid Waite and Smith’s deck in brighter colors, giving those in the U.S.A. an alternative to the University Press version. Hades, in Paris, published Manuel complet d’interpretation du tarot, claiming it was based on a pre-de Gébelin 1761 original. Jerry Kay came up with his own version of Crowley’s deck that he called The Book of Thoth: The Ultimate Tarot. And, Stuart Kaplan brought back the Swiss 1JJ deck from the Nuremberg Toy Fair, selling 200,000 copies in the first year and making tarot available in department stores across the U.S.

In 1968, the House of Camoin reproduced the classic 1760 Tarot de Marseille based on original pearwood woodcuts. The mysterious Frankie Albano redid Waite and Smith’s deck in brighter colors, giving those in the U.S.A. an alternative to the University Press version. Hades, in Paris, published Manuel complet d’interpretation du tarot, claiming it was based on a pre-de Gébelin 1761 original. Jerry Kay came up with his own version of Crowley’s deck that he called The Book of Thoth: The Ultimate Tarot. And, Stuart Kaplan brought back the Swiss 1JJ deck from the Nuremberg Toy Fair, selling 200,000 copies in the first year and making tarot available in department stores across the U.S.

The stage was now set for the 1969 deluge: at least five decks and twelve separate books where published! I won’t mention them all but they included Crowley’s Thoth book and deck (though not readily available for another two years), Cooke & Sharpe’s New Tarot for the Aquarian Age, an English-language edition of Grimaud’s Marseilles deck. Also books by Arland Ussher, Brad Steiger, Corinne Heline, Gareth Knight, C.C. Zain, Hilton Hotema, Frater Achad, Rodolfo Benavides, Elisabeth Haich, Sybil Leek, and Italo Calvino’s Italian short stories, ‘Il castello dei destini incrociati (“Castle of Crossed Destinies”). Every hippie pad had its requisite tarot reader.

1970 featured fewer books but even more decks, including the Rider-Waite and Palladini’s Aquarian. Stuart Kaplan at U.S. Games, Inc. started publishing his own decks.

The Tarot Renaissance was now fully underway.

For an even more extensive look at Tarot in America from 1910 to 1960 please see this Tarot Heritage page.

Many of you will be familiar with the tarot teachings of Paul Foster Case and the Builders of the Adytum (BOTA). Case took the idea of the adytum from a word long associated with the Mysteries. His idea was to build the adytum by meditating on the tarot Arcana. Adytum means inner shrine or holy-of-holies, from aduein meaning “not to be entered.” The adytum is said to contain the arcana, from the root arcus, “chest or box,” and arcere, “to ward off; shut up, keep,” from whence we get such concepts as the Ark of the Convenant, as a container of the secret knowledge between God and humanity that also wards off the profane. But what do these two terms, arcana and adytum, really mean and how do they relate to the tarot?

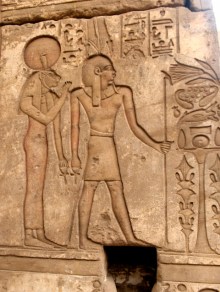

The phrase Arcana in the Adytum, first mentioned by Iamblichus, signifies the container of mysteries in the innermost sanctuary of a temple. Mystically speaking, this sanctuary must be built in the heart where the mysteries are directly experienced out of view of the profane. [This photograph is of the altar in the sanctum sanctorum at Karnak, which only the pharaoh was allowed to enter. The picture after it is of the spirit ascending into the starry sky in that sanctuary.]

Helena Blavatsky described the innermost shrine as:

“The Sanctum Sanctorum of the Ancients, i.e., that recess on the Western side of the Temple which was enclosed on three sides by blank walls and had its only aperture or door hung over with a curtain—also called the Adytum—was common to all ancient nations. . . . They regarded it—in its esoteric meaning—as the symbol of resurrection, cosmic, solar (or diurnal), and human. In Theosophy, therefore, the Holy of Holies represents the womb of nature, the female generative principle found in the mystery religions of Egypt, Babylon, India, Kabbalism, Masonry, etc. . . . The esoteric meaning of this arrangement typified cosmic, planetary and human resurrection or regeneration” (Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine, Vol. II).

The word arcana goes back at least to the Neoplatonist, Iamblichus (165-180 CE). Thomas Taylor, in translating Iamblichus’ On the Mysteries explains:

“For the highest order of intelligibles is denominated by Orpheus the adytum, as we are informed by Proclus in Timaeus. By the arcanum in the adytum, therefore, is meant the deity who subsists at the extremity of the intelligible order [i.e. Phanes]; and of whom it is said in the Chaldean Oracles, ‘that he remains in the paternal profundity, and in the adytum, near to the god-nourished silence.’ . . . And all things remain perfect and entire, because the arcana in the adytum are never disclosed. Hence, in those particulars in which the whole of things possesses its safety, I mean in arcana being always preserved occult, and in the ineffable essence of the Gods, never receiving a contrary condition; in these, terrestrial daemons cannot endure.”

The Abbot Trithemius (1462-1516) defined arcana as “a synthesis of Hermetic alchemical doctrine, Pythagorean numerology, astrological correspondences, and Cabalistic word magic” (Trithemius and Magical Theology by Noel L. Brann). It was Trithemius’ cryptogram that was employed in the “cipher manuscripts” upon which the Golden Dawn rituals and tarot correspondences were based.

Paracelsus (1493-1591) uses the word in his philosophy of alchemical medicine. He tells us that in contrast with our bodily being, arcana are immortal and eternal, “they have the power of transmuting, altering and restoring us, and are to be compared to the secrets of God, being vital in human health” (Paracelsus, Archidoxies, Bk V, trans. A.E. Waite).

It was in the adytum that the Ark of the Covenant was kept. The arcana (plural form of arcanum) contain and preserve the hidden wisdom, the esoteric, versus exoteric knowledge. This distinction is made explicit by Eckartshausen, a favorite author of A.E. Waite, in speaking of the different roles of priest and prophet, where the prophet, not the priest, held the inner truth of the arcanum in the adytum:

“The wisdom of the ancient temple alliance was preserved by priests and by prophets. To the priests was confided the external,—the letter of the symbol, hieroglyphics. The prophets had the charge of the inner truth, and their occupation was to continually recall the priest to the spirit in the letter, when inclined to lose it. The science of the priests was that of the knowledge of exterior symbol. That of the prophets was experimental possession of the truth of the symbols. In the interior the spirit lived. There was, therefore, in the ancient alliance a school of prophets and of priests, the one occupying itself with the spirit in the emblem, the other with the emblem itself. The priests had the external possession of the Ark, of the shewbread, of the candlesticks, of the manna, of Aaron’s rod, and the prophets were in interior possession of the inner spiritual truth which was represented exteriorly by the symbols just mentioned” (The Cloud upon the Sanctuary (c. 1790) by Karl von Eckartshausen (translated by Madame Isabel de Steiger)).

The Golden Dawn named their tarot rites of the 12 Zodiacal and 7 Planetary Major Arcana after the items mentioned in the quote above: “The Table of the Shewbread” and the “Ritual of the Seven-Branched Candlestick,” respectively, making clear that for them the Ark was the Arcana.

In 1782 Count Cagliostro gathered his research in secret societies into a body of knowledge known as the Arcana Arcanorum, or A. A., consisting of a series of magical practices that stressed “internal alchemy.”

Although he doesn’t mention arcana, Etteilla tells us of the mystical arrangement of these cards in the Temple of Ptah at Memphis, “Upon a table or altar, at the height of the breast of of the Egyptian Magus, were on one side a book or assemblage of cards or plates of gold.” [The photograph to the right is of an image at the entrance to Ptah’s temple at Thebes showing Pharaoh making his offerings with Shekmet, wife of Ptah, giving him strength and direction.]

In 1863 Paul Christian (pseudonym of J-P. Pitois) wrote a novel called L’homme rouge des Tuileries, which tells of an encounter between Napoleon and a Benedictine monk who possesses an occult manuscript. This manuscript described seventy-eight symbolic houses or pictorial keys, referred to as Arcana. Virtually the same Egyptianized descriptions of the Arcana appeared in Christian’s 1870 Histoire de la magie, where they were finally acknowledged as the tarot.

Ely Star’s 1888 work, Mystéres de l’Horoscope contains a chapter on the tarot based almost entirely on Paul Christian. He was first to use the terms Major Arcana and Minor Arcana, and the following year they also appeared in Papus’ book Tarot of the Bohemians, suggesting that these terms were already in general use.

Blavatsky believed the Arcana were key to the science of the soul.

“There is a regular science of the soul. . . . This science, by penetrating the arcana of nature far deeper than our modern philosophy ever dreamed possible, teaches us how to force the invisible to become visible; the existence of elementary spirits; the nature and magical properties of the astral light; the power of living men to bring themselves into communication with the former through the latter” (Blavatsky, Isis Unveiled, Vol. 1).

The term arcana continually calls us back to the spirit of the hieroglyphs that make up the tarot, which can only become known in the astral light of the inner temple of the heart. We must make of ourselves a sacred place to receive and contain the inner spiritual truth that can, in turn, transmute, alter and restore us.

Added: for a modern perspective on arcanum check out the definition from Inna Semetsky here.

I went to visit my daughter in Los Angeles and for the first time saw the exhibits at the J. Paul Getty Museum. While the collection on view is small, there were quite a few pieces from Renaissance Italy. It’s always astounding to me how much of the art from that period portrays images similar to those in the tarot. Judge for yourself:

The Hermit – circa 1510 century earthenware jar. Also similar to the RWS 5 of Pentacles.

The World – 15th century missal

The Tower – circa 1525 earthenware platter

Judgment – 15th century painting (here a saint carries the flag with the red cross rather than it hanging from the trumpet blown by an angel)

The RWS 4 of Cups – circa 1535 earthenware platter

This is not a Major Arcana image but rather is similar to the man under the tree in the RWS 4 of Cups created in 1909. The description card says: “The young man in the center is bound to a tree. This image, popular in Italy in the 1500s, is an allegory of love, depicted as a bittersweet force that holds its victims captive.”

First, I need to be forthcoming and let you know that despite my 1,000+ collection of tarot decks, the Rider-Waite-Smith (RWS) Tarot is my all-time favorite (not that I don’t like and use many others). I’ll talk about the reasons another time. Now I just want to offer up this tidbit of publishing history.

This deck, first published in December 1909 simply as “Tarot Cards,” was available more-or-less continually from 1910 until 1939 when Rider appears to have ceased publication. This may have been because of the WWII bombings when paper was scarce and the printing plates destroyed. French and Italian decks had never been easily available in England as such imports were heavily taxed. The Waite-Smith Tarot Cards were not officially republished until 1971 when the publisher/importer Waddington Playing Card Co Ltd. and U.S. Games, under a license from Rider & Co., jointly began publishing a version printed by A. G. Mueller in Switzerland.

I was always curious why such a popular deck was out-of-print for so long, until I came across this autobiography by one-time London bookseller Albert Meltzer called I Couldn’t Paint Golden Angels (Oakland CA: AK Press, 1996) and online here. As Meltzer tells it:

One of the minor curiosities I found when bookselling [he owned a bookstore on Gray’s Inn Rd.] was that one was constantly asked for tarot cards. For years these had been illegal — the ‘devil’s bible’ — and imports were banned. Any pretext that it was ‘only a game’ was dismissed by Customs. Tarot readers lined up at Bow Street every Monday, to be fined with the prostitutes, palm readers and graphologists (the latter have since blossomed out as forensic scientists).

Then the post-war Labour Government abolished the Witchcraft Act in 1946 [the actual year was 1951]. It was a favour to the journalist Hannen Swaffer* who had campaigned in the mainstream press for the Labour Party for years but refused an offer of the Lords. He merely asked for political relief to be given to the spiritualists. They were banned under the Witchcraft Act, and it was such medieval nonsense one could not amend it so it was abolished and so incidentally dream interpreters, psychics, tarot readers and soothsayers were legalised. Thus Britain emerged officially from the Dark Ages. . . .

It was in order, therefore, to import Tarot cards but they were taxed ‘as a game’. For years it had been insisted they were not a game. If they were religious appurtenances even of witchcraft, now legal, or at least not illegal, they could not incur tax. I tried fighting the Customs on this, but with no success. I could never afford to sue them, but tried to persuade the main importers, John Waddington, to do so. They, however, preferred paying tax and having it kept as a ‘game’. It is curious how this nonsense upset the police. The bookshop was actually raided to see if I had imported Tarot cards and not paid tax on them. The police were quite apologetic. When I explained about the Witchcraft Act they were not sure if I was being sarcastic or not. Neither was I.

So, from 1939 until 1951 (the year Pixie Smith died) it appears that fortune-telling cards were considered, in England, to be illegal under the Witchcraft Act, and no one was willing to take this issue to court. After 1951 and until the late sixties they were probably simply thought strange and old fashioned. The gap was filled for a while by Rolla Nordic who issued her own version of a Marseille tarot. Then, some old works on tarot were republished, and new works began to appear in the United States.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., University Books began publishing its own version of the deck in the early sixties (followed by Merrimack and Frankie Albano’s Tarot Productions), ceasing when U.S. Games started enforcing a copyright in 1971. Read my discussion of the 1969 Tarot Renaissance here.

*Slightly off-topic but to fill in some gaps in the quote above: In Great Britain, in 1951 the Fraudulent Mediums Act replaced the 1735 Witchcraft Act, which had increasingly been applied to Spiritualists and mediums. The last person to be convicted under the Witchcraft Act was Helen Duncan who in 1943, during a séance in Portsmouth, channeled a young man who told the gathering, which included his mother, that his ship had been sunk. The mother contacted the War Office asking for details. An investigation was launched into Duncan’s activities prompted by this revelation of top-secret information during war time. Supposedly the authorities became concerned that the medium might make pronouncements about the D-Day plans. Helen Duncan was tried and convicted in 1944, serving nine months in prison. The journalist and ghost-hunter Harry Price had investigated Helen Duncan’s ectoplasmic mediumship years before, and he claimed to have proven her a fraud. The British Society of Paranormal Studies and Duncan’s granddaughter recently have been petitioning the government for a pardon.

As a result of his own interests in Spiritualism and spurred on by the conviction of Helen Duncan, the popular journalist Hannen Swaffer (who was influential in and for the Labour Party), asked for restrictions on Spiritualism to be lifted as a reward for his services. To do so, the Government had to abolish the medieval Witchcraft Act. Three years later Spiritualism was officially recognized as a religion.

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Recent Comments