You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Book/Story/Poetry Reports’ category.

One of the simplest ways to start writing your own tarot poetry is to begin with the haiku format. There’s something about following it’s basic rules that frees up the creative sense. Since there are three lines you can either dedicate the whole poem to one card or use it for a three-card reading—one line for each card in your spread. (I write a haiku for each of the three cards and then take one line from each to form a fourth haiku that integrates those three cards.) Different decks tend to evoke entirely different “voices” in your haiku. Try it, and you’ll see what I mean.

Want some inspiration? You’ll find lots of examples, support and no criticism at Aeclectic’s Tarotforum haiku thread here.

The following are a few haiku rules, which you can feel free to break or use as you will.

A haiku describes natural phenomena in the fewest number of words, making an indelible impression on the reader. It calls attention to an observation and in effect says, “Look at this” or “Think about this.”

It consists of 17 syllables, or less, in three lines:

5 syllables

7 syllables

5 syllables

Guidelines (follow only if you wish):

• Use the present tense.

• No titles or rhymes (except to name your card, if you wish)

• Include two images that create harmony or contrast so each enriches the understanding of the other.

• Either the first or second line ends with a colon, long dash or ellipsis (marked or not).

• The two parts create a spark of energy, like the gap in a spark plug.

• Limit the use of pronouns.

• Traditionally, each haiku contains a seasonal reference.

• Use common, natural, sensory words. Avoid gerunds and adverbs.

• Images often begin wide-angle, then medium range and zoom in for a close up.

• Present what causes the emotion rather than the emotion itself.

Do you have a tarot haiku? If so, please share it via the comments.

Do you have a tarot haiku? If so, please share it via the comments.

Here’s one based on a very literal description of the 6 of Pentacles:

Hands catch falling coins.

Under the balance, someone

reaches — emptiness.

“For in truth, this story begins not with bones in a Parisian graveyard but with a deck of cards.

“The Devil’s Picture Book.”

—from Sepulchre, p. 5.

Kate Moss, author of Labyrinth, has written a new novel called Sepulchre about the lives of two women who are linked through a tarot deck. Here Kate Moss discusses her use of tarot in the novel. You’ll find other video discussions of the work at youtube. You can see the eight tarot cards created for the deck here and an explanation of how the characters relate to the cards here.

Added: I finally finished Sepulchre and don’t even feel like writing a review of it. The core idea of an original deck linking two women across time was interesting and the evocation of 19th century France was okay, but ultimately none of the characters was particularly likeable and the ending was meaningless. Moss really needed someone to ask her, while she was still writing, what the point of the story was, as ultimately it led nowhere.

I haven’t looked at much recent tarot poetry, but the web turns out to be a wonderful place to explore it. Here’s a few sites that offer something different or intriguing:

At heelstone.com’s poetry site you’ll find Tarot Poems by Mike Timonin, with Art by Cindy Duhe, presented in a very tarot-appropriate way. Click on the rapidly changing tarot card images and you’ll be taken to a poem determined by the shuffle. Want another card and poem? Shuffle the deck again.

You’ll also find a poem by Michael Gerald Sheehan for every card at Moon Path Tarot.

Tarot Poems by Donna Kerr from her book of poetry Between the Sword and the Heart.

Tarot Poetry by Rachel Pollack.

Here is one of the oldest tarot poems in existence: a sonnet by Teofilo Folengo, appearing in his 1527 work Caos del Triperiuno written under the pseudonym Merlini Cocai. The work includes a series of poems representing the individual fortunes of various people as revealed by cards dealt them. The summary sonnet below mentions each of the 22 Trump cards, which I’ve referenced by their number to the right of the line on which they appear. It helps to understand that Death is female in Italian, la morte, and Love (Cupid) is male. Love claims that although Death rules the physical body, Love never dies and therefore death is but a sham.

Love, under whose Empire many deeds (6, 4)

go without Time and without Fortune, (9, 10)

saw Death, ugly and dark, on a Chariot, (13, 7)

going among the people it took away from the World. (21)

She asked: “No Pope nor Papesse was ever won (5, 2)

by you. Do you call this Justice?” (8 )

He answered: “He who made the Sun and the Moon (19, 18 )

defended them from my Strength. (11)

“What a Fool I am,” said Love, “my Fire, (0, 16)

that can appear as an Angel or as a Devil (20, 15)

can be Tempered by some others who live under my Star. (14, 17)

You are the Empress[Ruler] of bodies. But you cannot kill hearts, (3)

you only Suspend them. You have a name of high Fame, (12)

but you are nothing but a Trickster.” (1)

Translated by Marco Ponzi (Dr. Arcanus) with help from Ross Caldwell, members of Aeclectic Tarot’s TarotForum, and by comparisons with the translation found in Stuart Kaplan’s Encyclopedia of Tarot, Vol II, p. 8-9 (read the discussion here). The first picture is from a 1485 Triumph of Death fresco on the wall of a Confraternity Chapel in Clusone, Italy. It depicts Death as an Empress before whom all others bow. The second picture is from Savonarola’s Sermon on the Art of Dying Well, published circa 1500.

See the translation of one of Folengo’s fortune-telling sonnets at taropedia – here.

Added: Check out the poetic concept of rhyme applied to visual aspects of the tarot in Enrique Enriquez’s article on “Eye Rhyme.”

. . . With my gypsy ancestress and my weird luck

And my Tarot pack and my Tarot pack . . . (at minute 1:43)

See more Sylvia Plath videos here (then search on her name).

Added: It turns out that the original manuscript of Sylvia Plath’s book, Ariel, was ordered according to the Tarot and Qabala—with the first twenty-two poems associated with the Major Arcana and the next ten with the ten pips and sephiroth followed by the four ranks of the Court and then the four suits. This ordering is now apparent in Ariel: The Restored Edition (2004). All of this is explained in an article by Julia Gordon-Bramer for the journal Plath Profiles. Download a pdf of Gordon-Bramer’s article here.

When did the modern tarot renaissance actually begin? It’s always hard to pinpoint the beginning of a movement but here are some events worth noting that lead up to the breaking of the dam in 1969. I’m looking for corrections and additions to the information below, plus tarot stories from the 60s and early 70s. Please share them in the comments.

The 1940s saw some interesting tarot activities that set the stage for the later renaissance. The Crowley-Harris Thoth deck was completed and published in a limited edition of 200 in monochrome brown by Chiswick Press, but these were not available to the general public. In 1947 Paul Foster Case published his masterful work The Tarot: A Key to the Wisdom of the Ages, based on his tarot correspondence course. In France, Paul Marteau came out with his hugely influential book Le Tarot de Marseille that noted the symbolic significance of the smallest details in the deck. In Brazil, J. Iglesias Janeiro, published his book La Cabala de Prediccion, which popularized the turn-of-the-century Egyptianized Falconnier/Wegener cards. It became a center-piece of his important occult school, known mostly in Latin America. Meanwhile, in the U.S.A., Dr. John Dequer published The Major Arcana of the Sacred Egyptian Tarot, which was his revised version of those same Egyptianized cards, similar to what was already being used by C.C. Zain’s Brotherhood of Light correspondence school.

The Insight Institute in Surrey England started up their tarot correspondence course (later published in a book by Frank Lind) and produced their occultized version of the Marseilles deck (eventually published as the R.G. Tarot). Also appearing was an unusual book, solely on the psychological dimension of the Minor Arcana cards numbered 2-10 as they are associated with one’s birthday. It was Pursuit of Destiny by Muriel Bruce Hasbrouck, who had studied with Aleister Crowley when he was in the United States. Tudor Publishing’s The Complete Book of the Occult and Fortune Telling became the sole source in English of the unique Tarot card interpretations from Eudes Picard’s 1909 French work, Tarot.

The 1940s also saw the incorporation of Tarot imagery in surrealist artworks such as Victor Brauner’s “The Surrealist,” and in Jackson Pollack’s “Moon Woman” (both of which I happened upon when I visited the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice following the 2000 Tarot Tour with Brian Williams). William Gresham’s novel, Nightmare Alley, featured a carny mentalist who reads tarot and the book is presented as a twenty-two card reading. A year later Tyrone Power played the lead in the movie version featuring two tarot readings by Joan Blondell. Charles Williams’ landmark tarot novel, The Greater Trumps came out just as this decade ended and the next one began.

The 1950s produced even fewer tarot works. George Fathman published The Royal Road: A Study in the Egyptian Tarot, which used Dequer’s version of the Falconnier/Wegener cards. Paul Christian’s seminal work The History and Practice of Magic was translated from French to English, providing the original source material on which all those Egyptian-style decks were based. Arcanum Books reissued Papus’ The Tarot of the Bohemians with an introduction by librarian Gertrude Moakley, who noted the influence of tarot on creative writers and in psychology. Off in the Netherlands, Basil Rakoczi published the English language letterpress art book: The Painted Caravan: A Penetration into the Secrets of the Tarot Cards. Yet, the tarot seemed likely to fade away from popular view.

1960 started out the decade with a bang. University Books published Waite’s A Pictorial Key to the Tarot for an American readership, as well as a deck: Tarot Cards Designed by Pamela Colman Smith and Arthur Edward Waite. Eden Gray self-published her Tarot Revealed that still sells well to this day. In England Rolla Nordic came out with The Tarot Shows the Path: Divination through the Tarot. These last two books showed a clear shift in interest to practical tarot readings for the masses. Muriel Hasbrouck’s greatly overlooked 1940s work was re-published.

As the 60s progressed we got two heavy metaphysical works: Mouni Sadhu’s Tarot: A Contemporary Course of the Quintessence of Hermetic Occultism, and Mayananda’s The Tarot for Today, a study of Crowley’s material in the Book of Thoth (despite the latter’s being unavailable). The Brotherhood of Light came out with a new, revised edition of their 1930s Tarot deck. Idries Shah claimed, in The Sufis, that the Tarot was a Sufi creation. Influenced by T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” and Yeats’ involvement in the Golden Dawn, poets like Robert Creeley, John Weiners, Diane Wakowski, Sylvia Plath, Philip Lamantia and Diane di Prima began using tarot imagery in their poems. While not published until 1974, Jack Hurley and John Horler worked on “The New Tarot,” a Jung-based deck, at the Esalen Institute throughout the 60s, influencing many who passed through there.

In 1966 Gertrude Moakley set tarot history on it’s ear with her groundbreaking research in The Tarot Cards Painted by Bembo. The Grand Tarot Belline deck was published in Paris, as was a new edition of Oswald Wirth’s 1927 book, Le Tarot des imagiers du moyen age, that included his 22 card deck. Beginning in 1966 and running through 1971 the day-time TV soap opera Dark Shadows gave many people their first glimpse of a tarot deck as various episodes featured readings with the Marseille deck.

In 1966 Gertrude Moakley set tarot history on it’s ear with her groundbreaking research in The Tarot Cards Painted by Bembo. The Grand Tarot Belline deck was published in Paris, as was a new edition of Oswald Wirth’s 1927 book, Le Tarot des imagiers du moyen age, that included his 22 card deck. Beginning in 1966 and running through 1971 the day-time TV soap opera Dark Shadows gave many people their first glimpse of a tarot deck as various episodes featured readings with the Marseille deck.

By 1967, even a paper company jumped on the bandwagon with its advertising Linweave Tarot Pack that gave David Palladini his introduction to tarot design (see card on right). Helios Books in England published a small edition of the Golden Dawn’s Inner Order tarot teachings, Book T. Doris Chase Doane came out with two books that helped popularize the Brotherhood of Light Egyptian tarot deck in America. Sidney Bennett wrote Tarot for the Millions.

In 1968, the House of Camoin reproduced the classic 1760 Tarot de Marseille based on original pearwood woodcuts. The mysterious Frankie Albano redid Waite and Smith’s deck in brighter colors, giving those in the U.S.A. an alternative to the University Press version. Hades, in Paris, published Manuel complet d’interpretation du tarot, claiming it was based on a pre-de Gébelin 1761 original. Jerry Kay came up with his own version of Crowley’s deck that he called The Book of Thoth: The Ultimate Tarot. And, Stuart Kaplan brought back the Swiss 1JJ deck from the Nuremberg Toy Fair, selling 200,000 copies in the first year and making tarot available in department stores across the U.S.

In 1968, the House of Camoin reproduced the classic 1760 Tarot de Marseille based on original pearwood woodcuts. The mysterious Frankie Albano redid Waite and Smith’s deck in brighter colors, giving those in the U.S.A. an alternative to the University Press version. Hades, in Paris, published Manuel complet d’interpretation du tarot, claiming it was based on a pre-de Gébelin 1761 original. Jerry Kay came up with his own version of Crowley’s deck that he called The Book of Thoth: The Ultimate Tarot. And, Stuart Kaplan brought back the Swiss 1JJ deck from the Nuremberg Toy Fair, selling 200,000 copies in the first year and making tarot available in department stores across the U.S.

The stage was now set for the 1969 deluge: at least five decks and twelve separate books where published! I won’t mention them all but they included Crowley’s Thoth book and deck (though not readily available for another two years), Cooke & Sharpe’s New Tarot for the Aquarian Age, an English-language edition of Grimaud’s Marseilles deck. Also books by Arland Ussher, Brad Steiger, Corinne Heline, Gareth Knight, C.C. Zain, Hilton Hotema, Frater Achad, Rodolfo Benavides, Elisabeth Haich, Sybil Leek, and Italo Calvino’s Italian short stories, ‘Il castello dei destini incrociati (“Castle of Crossed Destinies”). Every hippie pad had its requisite tarot reader.

1970 featured fewer books but even more decks, including the Rider-Waite and Palladini’s Aquarian. Stuart Kaplan at U.S. Games, Inc. started publishing his own decks.

The Tarot Renaissance was now fully underway.

For an even more extensive look at Tarot in America from 1910 to 1960 please see this Tarot Heritage page.

An issue came up on one of the forums about which is the best book from which to learn about the Crowley-Harris Thoth deck. The answer for almost everyone is, without question, Aleister Crowley’s Book of Thoth. This, despite the fact that, for most beginners in esoteric studies, it seems impenetrable. Books by Duquette and Banzhaf are proposed as intermediaries and I agree they are excellent choices, but a problem occurs when Angeles Arrien’s name comes up. Her Tarot Handbook: practical applications of ancient visual symbols takes a completely different approach to the deck, which is often characterized as the “make up anything you want” variety—though it isn’t that at all. I should mention I took several classes with Angie on the Thoth deck starting in 1977, and so I’m not at all objective in my views.

Angie’s approach is based on Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious and the meaningful repetition of archetypal images and themes across world-wide human cultures. The statement by Arrien that probably infuriates people the most is: “I read Crowley’s book that went with this deck and decided that its esotericism in meaning hindered, rather than enhanced, the use of the visual portraitures that Lady Frieda Harris had executed.” Of key importance was that Arrien experienced a powerful response to the deck that did not arise from an esoteric OTO or Golden Dawn background. It was not specifically a rejection of Crowley, though it is easy to take it as such.

Instead, Arrien recognized most of the symbols from her study of anthropology and mythology. As a result she felt that “a humanistic and universal explanation of these symbols was needed so that the value of Tarot could be used in modern times as a reflective mirror of internal guidance which could be externally applied.” She believed that the Thoth deck symbols could be read in an other-than-esoteric way—specifically, as cross-cultural psychological symbols (archetypes from the collective unconscious). Her book offers this alternate perspective, based on the work of Carl Jung, Marie Louise von Franz, Joseph Campbell, Ralph Metzner, Mircea Eliade and Robert Bly.

In essence, Arrien asked: What do these symbols tell us if we strip away the esotericism and look at them purely as symbols and archetypes from the collective unconscious reflecting myths and images that have appeared across many cultures?

I see this simply as an alternate reading of the deck—not as a demand that we discount Crowley—but, rather, asking what can be seen if we do ignore Crowley? Is there anything else to this deck? Do real ‘true’ symbols transcend fixed definitions? Can they transcend any and all dogma?

We might also ask: If Crowley’s book were lost (along with all other esoteric texts), would future generations be able to reconstitute and find anything meaningful in these 78 images? Would this deck still offer something capable of informing our thoughts and actions?

It turns out that this is a valid question, for at least one person involved in the online discussion (and perhaps many others) felt that the Thoth deck is based on a specific language of symbols, defined by Crowley, such that, without his text the symbolism and the deck become meaningless. To remove Crowley, then, is to kill the Thoth deck—to make it worthless. In fact, as explained to me, symbols contain no meaning outside of the stated definitions of an individual. Strip symbols of definition and they either convey no information or they mean anything one likes.

This is absolutely contrary to the understanding of symbols held by such people as Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, the French magician, Eliphas Lévi, and countless others who have written extensively on symbolism and who believe that the meaning of the symbol is inherent in its nature. “Symbols can thus be understood as metaphors for archetypal needs and intentions or expressions of basic archetypal patterns . . . which are ultimately inherent in the human mind-brain” (Anthony Stevens, Ariadne’s Clue: A Guide to the Symbols of Humankind).

Furthermore, symbolism is a sacred, living language that reflects divinity through like vibrations. From this principle arose the occult ‘doctrine of correspondences,’ which says that something that is red, for instance, shares some kind of energy and meaning with other things that are red. Thorns that pierce are the protective weapons and barriers to the alluring rose whose scent also draws the bees. Even an esoteric interpretation takes such elements into account.

Many spiritual teachers do not fear the subjective, for they see each person as partaking of the Divine. The esotericist Manly Palmer Hall wrote in The Secret Teaching of All Ages: “Like all other forms of symbolism, the Tarot unfailingly reflects the viewpoint of the interpreter himself. This does not detract from its value, however, for symbolism is one of the most useful instruments of instruction in the spiritual arts, because it continually draws from the subjective resources of the seeker the substance of his own erudition.”

Certainly Crowley’s erudition is great, and we benefit from the knowledge he put into the Thoth book and deck (his book is magnificient!). But, if we stop there, we have not done our own work. There may be other interpreters of the Thoth deck who can also point us down what has been called “the royal road” of Tarot. Still, eventually we must make the path our own—there’s no getting around that.

The Egyptologist, R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz in Symbol and the Symbolic tells us that symbols are different than an abstract alphabet in that we can reconstitute their meanings: “Any manner of writing formed by means of a conventional alphabetical, arbitrary system can, over time, be lost and become incomprehensible. On the other hand, the use of images as signs for the expression of thought [hieroglyphics] leaves the meaning of this writing, five or six thousand years old, as clear and accessible as it was the day it was carved in the stone.” In The Temple in Man, Schwaller de Lubicz talks about the living quality of the symbol that can not survive too rigid of a definition: “To explain a symbol is to kill it; it is to take it only for its appearance; it is to avoid listening to it. By definition, the symbol is magic, it evokes the form bound in the spell of matter. To evoke is not to imagine. It is to live, live the form.” (See Schwaller’s Egyptianized Tarot Trumps here.)

Most of all I appeal to Oswald Wirth who created the first truly esoteric Tarot deck (1889; revised in 1926) that is a significant influence behind all that have followed. Wirth, in Le Symbolisme Hermétique (translated by P. D. Ouspensky), wrote that symbols are meant to awaken us to our own freedom:

“Each thinker has the right to discover in the symbol a new meaning corresponding to the

logic of his own conceptions. As a matter of fact, symbols are precisely intended to awaken ideas sleeping in our consciousness. They arouse a thought by means of suggestion and thus cause the truth which lies hidden in the depths of our spirit to reveal itself. . . . They especially elude minds which . . . base their reasoning only on inert scientific and dogmatic formulae. The practical utility of these formulae cannot be contested, but from the philosophical point of view they represent only frozen thought, artifically limited, made immovable to such an extent, that it seems dead in comparison with the living thought, indefinite, complex and mobile, which is reflected in symbols. . . . By their very nature the symbols must remain elastic, vague and ambiguous, like the sayings of an oracle. Their role is to unveil mysteries, leaving the mind all its freedom.”

“. . . Leaving the mind all its freedom.” It saddens me that the fears and anger provoked by Angeles Arrien’s book indicate a deep mistrust that the Thoth deck can survive the common touch of the “masses,” or that it has any worth whatsoever outside of Crowley’s text. It is felt that the mistakes and misconceptions in Arrien’s book (of which there admittedly are many) could create a devastating sense of betrayal in those who eventually find out that Crowley intended something different. This supposedly-fearful juxtaposition, however, led me to a much deeper appreciation of Crowley, while Angie encouraged independence and freedom in how I work with the deck and its symbols (not a good thing to those who see Crowley as the absolute and only fundament).

Although Crowley professed love for “the scarlet woman,” yet he feared the prostituting of his work, insisting that the deck and book always be sold together (it isn’t) and describing the deck’s potential use in fortune-telling as being a base and dishonest purpose (here -see text at the end). In fact, it seems that Crowley feared even the thought that anyone might claim independent insight into his deck for, despite her working diligently for five years with him to produce the deck, Crowley made clear that his student and artist, Frieda Harris, at no time contributed “a single idea of any kind to any card, and she is in fact almost as ignorant of the Tarot and its true meaning and use as when she began.” What hope is there, then, for the rest of us?

But, hope does exists, for the ever-contradictory Aleister Crowley (using the pseudonym “Soror I.W.E.“) wrote in his introductory biographical note to the Book of Thoth, that “the accompanying booklet [this book] was dashed off by Aleister Crowley, without help from parents. Its perusal may be omitted with advantage.“ If Crowley was of two-minds about how necessary his own book was to the deck, then is it at all surprising that we should be, too? I think most of us can agree that Frieda Harris’ innovative use of Steinerian ‘Synthetic Projective Geometry,’ described here, which was not in any way Crowley’s contribution, certainly deepens the effect of the deck’s imagery on the psyche.

I can only hope that, if you care about the Thoth deck, that each of you are brave enough to make up your own minds and feel free to “do as you will.” I leave you with this thought from old Aleister:

Know Naught!

All ways are lawful to innocence.

Pure folly is the key to initiation.

Eden Gray at the ’97 International Tarot Congress, dressed as the Sun, standing between Mary Greer as the Hermit and Barbara Rapp, organizer of the Los Angeles Tarot Symposiums.

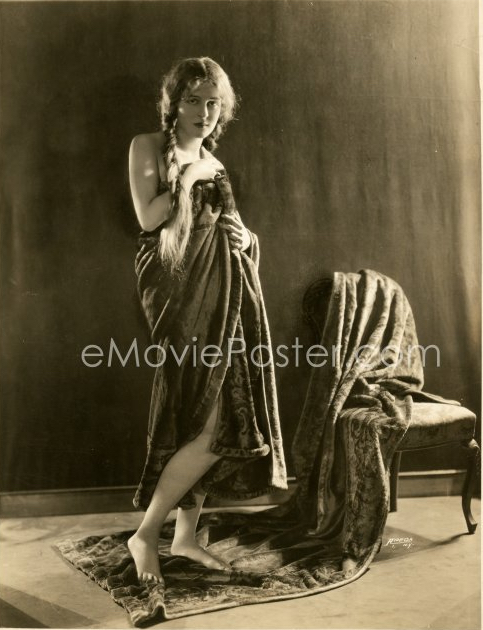

Eden Gray (born June 9, 1901) began life as Priscilla Pardridge, Chicago debutante and second cousin to Princess Engalitcheff, wife of the Russian vice counsel. Still in her teens, Priscilla decided to become a stage actor. Despite her family’s owning Chicago’s Garrick Theatre (as well as a major department store), her father “snatched her from the footlights,” so she took a menial job in another department store. Before long she slipped off to New York where, at nineteen years of age, and without her parents’ knowledge, she married fellow-Chicago poet, novelist and screenwriter Lester Cohen (who wrote the screenplay for Of Human Bondage among others).

Adopting the stage name, Eden Gray, from 1920-1933 she was in a series of Broadway plays, including Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, at New York’s Empire Theatre in 1928 (photo on right), and Doctor X on Broadway (see poster). She also performed supporting roles in three movies, being best known as Pamela Gordon in the 1925 film Lovers in Quarantine, and appearing as late as 1942 with Ronald Reagan in King’s Row (despite only a fleeting glimpse of her at a window in the film, she and Reagan shared an interest in positive thinking and astrology). In addition to all this she took a several year trip with her husband, which he described in his book, Two Worlds: An Account of a Journey around the World. During World War II, she put her acting career on hold to become a lab technician with the Women’s Army Corps.

Adopting the stage name, Eden Gray, from 1920-1933 she was in a series of Broadway plays, including Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, at New York’s Empire Theatre in 1928 (photo on right), and Doctor X on Broadway (see poster). She also performed supporting roles in three movies, being best known as Pamela Gordon in the 1925 film Lovers in Quarantine, and appearing as late as 1942 with Ronald Reagan in King’s Row (despite only a fleeting glimpse of her at a window in the film, she and Reagan shared an interest in positive thinking and astrology). In addition to all this she took a several year trip with her husband, which he described in his book, Two Worlds: An Account of a Journey around the World. During World War II, she put her acting career on hold to become a lab technician with the Women’s Army Corps.

After living in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Indiana, Paris and London and working in radio and on the London stage, Gray moved back to New York. She earned a doctorate of divinity degree from the First Church of Religious Science and then lectured and taught classes in Science of Mind. Gray also got to know librarian Gertrude Moakley who, since the early 1950s, had been researching tarot’s origins in Renaissance Italy (see bio of Moakley here).

Eden Gray ran a bookstore and publishing company called “Inspiration House,” one of the few places where a person could buy tarot cards and take tarot classes in the late 1950s and ’60s. Her customers complained that the available books were not easy to understand, so she spent weekends in the country coming up with a more accessible way of approaching the cards.

Eden Gray ran a bookstore and publishing company called “Inspiration House,” one of the few places where a person could buy tarot cards and take tarot classes in the late 1950s and ’60s. Her customers complained that the available books were not easy to understand, so she spent weekends in the country coming up with a more accessible way of approaching the cards.

Eden Gray self-published her first book, Tarot Revealed: A Modern Guide to Reading the Tarot Cards in 1960 to which she applied her “New Thought” perspective (see my earlier post here). She followed up her first success with two more tarot books: A Complete Guide to the Tarot (1970) and Mastering the Tarot: Basic Lessons in an Ancient, Mystic Art (1971). All feature graphics by her artist son Peter Gray Cohen. These books have remained continuously in print and are still among the best-selling tarot books today.

My personal favorite is Mastering the Tarot, as the card meanings are the richest of the three, and it gives practical demonstrations of interpreting the cards through sample readings. Lesson 18, “The Use and Misuse of the Tarot,” is a small gem of “New Thought” philosophy and positive thinking applied to the cards. Gray advises:

“So watch for the pitfalls when you read the cards; recognize how very suggestible everyone is—and then go ahead and use the cards for good. . . . Give those for whom you read encouragement to strive for their highest ideals. The seeds you plant can blossom into lovely flowers of accomplishment.”

Along with various editions of the Rider-Waite-Smith deck (de Laurence, University Books, Albano-Waite, Merrimack, U.S. Games, Inc.), Eden Gray’s tarot books formed the main impetus to the hippie adoption of the Tarot as spiritual guide for navigating a world-turned-on-its-head, leading directly to the booming Tarot Renaissance that began in 1969 and continues to this day.

It was Eden Gray to whom we owe the term “Fool’s Journey,” appearing as the title of the Epilogue in A Complete Guide to the Tarot. She explained:

“The Fool represents the soul of everyman, which, after it is clothed in a body, appears on earth and goes through the life experiences depicted in the 21 cards of the Major Arcana, sometimes thought of as archetypes of the subconscious. Let each reader use his imagination and find here his own map of the soul’s quest, for these are symbols that are deep within each one of us.”

In 1960 she had already alluded to the idea, saying that the Fool “must pass through the experiences suggested in the remaining 21 cards, to reach in card 21 the climax of cosmic consciousness or Divine Wisdom”—an idea that resonated deeply with the hippies—and that Gray probably picked up from A.E. Waite who wrote about the “soul’s progress through the cards.”

In 1971, Gray moved to Vero Beach, Florida, where she focused on her art and spiritual ministry. She was a member of the Vero Beach Art Club and Riverside Theater and Theater Guild. In the 1990s several people contacted her about her earlier work in tarot, including Ron Decker and Janet Berres of the International Tarot Society. Berres honored Gray at their third International Tarot Congress in 1997 in Chicago with the Tarot Lifetime Acheivement Award. It was here that Eden Gray learned to her great astonishment just how truly revered she was for her seminal tarot books.

In 1971, Gray moved to Vero Beach, Florida, where she focused on her art and spiritual ministry. She was a member of the Vero Beach Art Club and Riverside Theater and Theater Guild. In the 1990s several people contacted her about her earlier work in tarot, including Ron Decker and Janet Berres of the International Tarot Society. Berres honored Gray at their third International Tarot Congress in 1997 in Chicago with the Tarot Lifetime Acheivement Award. It was here that Eden Gray learned to her great astonishment just how truly revered she was for her seminal tarot books.

(I received this bronze statue of the Hanged Man created by Eden Gray (see right) from Barbara Rapp at the Los Angeles Tarot Symposium for recognition of my work in tarot. Read about it’s significance while writing my Tarot Reversals book here. Read more about Eden Gray here.)

This adventurous, pioneering woman, and “Godmother of the Modern American Tarot Renaissance” died peacefully in her sleep at 97 years of age, on January 14, 1999 in Vero Beach, having driven herself to the hospital following a minor heart attack.

Her books (with first publication date):

- Tarot Revealed (1960)

- Recognition: Themes on Inner Perception (1969)

- A Complete Guide to the Tarot (1970)

- Mastering the Tarot (1971)

- The Harvest Home Natural Grains Cookbook with Mary Beckwith Cohen (1972)

- The Harvest Home Fresh Vegetables Cookbook with Mary Beckwith Cohen (1972)

- Marbling on Fabric with Daniel and Paula Cohen (1990)

You can hear her briefly in this replay of a Long John Nebel talk radio program from New York in 1964 (thanks to Kim). Be warned that she only gets in a couple of sentences in a show totally dominated by Walter Martin who wrote an anti-cult/occult book from a Christian perspective. Supposedly she appeared on other Nebel shows but I can’t find them on the net.

Just found: Eden Gray as “Angela” in The Firebrand,1924-25. She played the model of the Renaissance artist Benvenuto Cellini. The play was described as: “a modern farce masquerading in the trappings of the Renaissance, or a comedy of the sixteenth century “jazzed up” to delight a 1925 audience.” You can also see another photograph of her here.

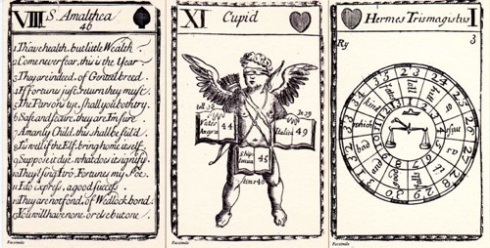

17th century – German Proverb decks

17th century – German Proverb decks Quite a few old German decks featuring proverbs and sayings that must have been used for obtaining advice and prognostication of how a situation would progress. The suits consist of Green Leaves (Spades), Red Hearts (Hearts), Yellow Bells (Diamonds) and Black Acorns (Clubs). Acorns (Clubs) are generally the worst suit, while the Green Leaves (Spades) are the best suit.

Quite a few old German decks featuring proverbs and sayings that must have been used for obtaining advice and prognostication of how a situation would progress. The suits consist of Green Leaves (Spades), Red Hearts (Hearts), Yellow Bells (Diamonds) and Black Acorns (Clubs). Acorns (Clubs) are generally the worst suit, while the Green Leaves (Spades) are the best suit.

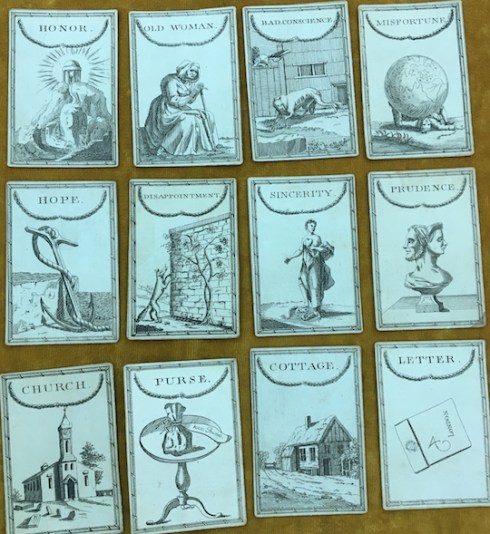

1791 – Every Lady’s Own Fortune Teller

1791 – Every Lady’s Own Fortune Teller

1790 to mid 19th century – The Career of Mlle. Lenormand

1790 to mid 19th century – The Career of Mlle. Lenormand Tawny Rachel, or The Fortune Teller; With some Accounts of Dreams, Omens and Conjurers

Tawny Rachel, or The Fortune Teller; With some Accounts of Dreams, Omens and Conjurers

1838 – Julia Orsini

1838 – Julia Orsini

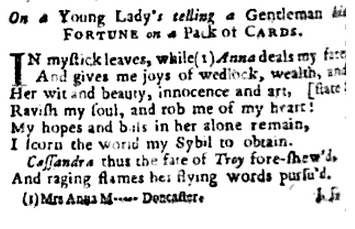

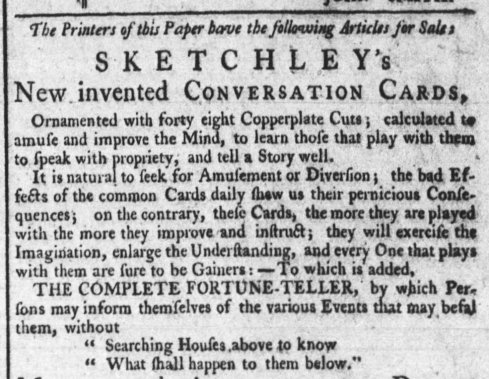

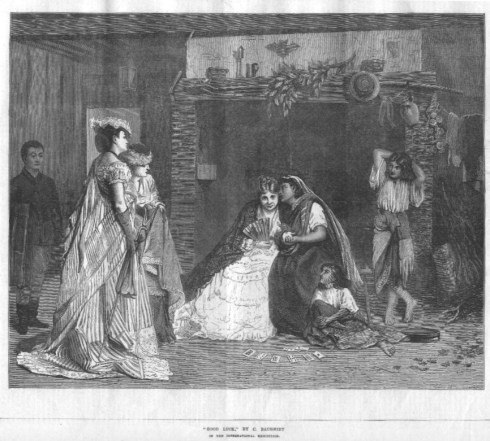

Never as ubiquitous as dice, palmistry or astrology, divination with cards goes back to at least the 16th century and probably earlier, though the form may not have been what we now call cartomancy, which emerged more recognizably in the 18th century. We can see from all the above that historically card divination was practiced mostly by illiterate gypsies, courtesans, soldier’s wives and old women, and by literate young women for whom it was a parlour game. It was largely scorned by men and more often officially ignored by legislation, until the stakes got higher. With the exception of Madame Lenormand’s fame, it wasn’t until a few men deemed the art worth mentioning and the decks or books worth writing that it was really acknowledged. Still, it was not to be taken too seriously and generally kept to the confines of frivolous social entertainment, yet all the while there was an underground of mostly older women who made a good, if precarious, living out of various forms of divination. (Out of more than 400 pre-1900 pictures I’ve found of cartomancers less than a dozen have been of male readers and most of them are making fun of the practice.) A. E. Waite integrated Chambers’ soldier’s wives card meanings into many of his Minor Arcana tarot interpretations, where they are still in use today.

Never as ubiquitous as dice, palmistry or astrology, divination with cards goes back to at least the 16th century and probably earlier, though the form may not have been what we now call cartomancy, which emerged more recognizably in the 18th century. We can see from all the above that historically card divination was practiced mostly by illiterate gypsies, courtesans, soldier’s wives and old women, and by literate young women for whom it was a parlour game. It was largely scorned by men and more often officially ignored by legislation, until the stakes got higher. With the exception of Madame Lenormand’s fame, it wasn’t until a few men deemed the art worth mentioning and the decks or books worth writing that it was really acknowledged. Still, it was not to be taken too seriously and generally kept to the confines of frivolous social entertainment, yet all the while there was an underground of mostly older women who made a good, if precarious, living out of various forms of divination. (Out of more than 400 pre-1900 pictures I’ve found of cartomancers less than a dozen have been of male readers and most of them are making fun of the practice.) A. E. Waite integrated Chambers’ soldier’s wives card meanings into many of his Minor Arcana tarot interpretations, where they are still in use today.

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Recent Comments