You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘RWS Tarot’ category.

I try to keep abreast of Tarot as it appears in fiction but somehow I missed this one: The Holy by Daniel Quinn (2002). The entire book is the playing out of a Tarot reading, made explicit by full-page illustrations of Rider-Waite-Smith cards that introduce book sections.

I try to keep abreast of Tarot as it appears in fiction but somehow I missed this one: The Holy by Daniel Quinn (2002). The entire book is the playing out of a Tarot reading, made explicit by full-page illustrations of Rider-Waite-Smith cards that introduce book sections.

The central what if is, “What if the God of the Bible was not the only God, and what if the “false gods” referred to in the ten commandments actually exist?” We can extend this to ask the questions: Who are they? and What do they want?—questions the author leaves only partially answered.

This is a Fool’s journey, cross country, undertaken by several different people, at first independently and then with converging stories, all foreseen in the Tarot reading that becomes explicit only as the tale evolves. Quinn is known for his philosophical novels, starting with the highly regarded Ishmael, for which he won the half-million dollar Turner Tomorrow Fellowship. Quinn is an original thinker whose process has been described as “seeing through the myths of this culture” or “ripping away the shades so that people can have a clear look at history and what we’re doing to the world.” It’s interesting that despite the centrality of the Tarot reading and Tarot illustrations in this book, the Tarot content is hardly ever mentioned and never discussed in the reviews I’ve read.

Synopsis: Sixty-plus year-old private detective Howard Scheim is hired by an acquaintance to discover if the “false gods” of the Bible really exist. In agreeing to discover if he can even undertake such an inquiry he interviews several people including a journalist, a tarot reader, a clairvoyant and a Satanist. Meanwhile the Kennesey family is undergoing upheaval as husband David decides to walk away from his job, his wife and his 12-year old son, Tim. Tim and his mother go searching for David and, when Tim becomes accidentally separated from his mother, Howard stumbles upon him and offers to help Tim find her. As it turns out both David and his son Tim are being courted by amoral, non-human “others” who plan to “wake up” humanity because their blindness is creating havoc. These “others,” who refuse to define themselves, are trickster beings, neither evil nor benevolent, who have existed far longer than homo sapiens. They have been known to enchant those humans who look to the physical world rather than to a transcendent being to benefit them.

The Celtic Cross Tarot reading shows Quinn to be knowledgeable about Tarot consulting. References to people named Case (P.F. Case authored an influential Tarot book) and John Dee (magician to Elizabeth I), as well as a road named Morning Star Path (a Golden Dawn offshoot was called the “Stella Matutina” or morning star) makes it clear that Quinn is referencing modern occult lore.

Tarot reader Denise starts by explaining that the first card in Howard’s reading indicates the predominant influence in the subject’s life. Howard draws the Seven of Swords and Denise asks Howard to tell her what it is about, explaining this is not her usual way of working but, “If I proceed normally, you’ll think I’m slanting it.”

He describes a thief stealing swords for a battle who has overlooked something (two swords left behind).” Denise summarizes it: “You’re getting ready for a battle and you’re overestimating your own cleverness and underestimating the strength of your enemy. You’re overconfident and you think you can’t be hurt in the enterprise you’ve planned. . . . The reading will center on the conflict you’re preparing for.”

The Seven of Swords is crossed by the Two of Pentacles: “The pentacles represent grave extremes: the beginning and the end, life and deah, infinite past and the infinite future, good and evil. Nevertheless, the young man is dancing.” Denise says he takes the situation too lightly.

The card above him is the Eight of Cups: “At best, you can hope for a strange journey, an adventure into darkness.”

The frontispiece illustration is that of the Seven of Cups, appearing in the reading in the environment position: “A man is disconcerted by an array of tantalizing apparitions of love, mystery, danger, riches, fame, and evil. Illusions will bedevil you. You’ll be pulled in many directions, and your choices will be confused.” Perhaps this is the underlying theme of not only this book but other works by Daniel Quinn: Humankind is bedeviled by the illusions of culture and civilization so that our choices are confused, centering on all the wrong things. Quinn has one of the characters quote Plato’s The Republic: “Whatever deceives can be said to enchant.” Adding, “Anyone who shakes off the deception shakes off the enchantment as well – and ceases to be one of you [a homo sapien].” The Holy, p. 260.

I’ve left out most of the interplay about the cards, and I won’t reveal more of the story as I hope you will explore this book for yourselves.

I went to see the play, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” last night. As I like to do, I drew cards before going so I could contemplate them during the performance. It enhances the experience for me to be more aware of the dynamics, character conflict and themes as they are occuring.

For those who don’t remember the movie with Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, or who never saw the play: A middle-aged couple, George and Martha, have invited a young couple, Nick and Honey, over for late night drinks after a dinner party. What follows is a series of drunken mind games getting more and more deadly as they all head straight for nuclear armageddon. It was played as a very black comedy. Luckily, it was done by a local troupe of fine actors who gave the play their own unique twist. I focused on George and Martha.

I hadn’t remembered many details of the drama, so I was thrilled by how perfect the cards turned out to be. I did two spreads. The first one was with the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot. What was I to think when three out of five cards were reversed Court Cards? As it turned out, the play provided excellent examples of how these Court Card types can “go wrong.”

• What is Martha’s core need or issue? King of Pentacles reversed.

• What is Martha’s core need or issue? King of Pentacles reversed.

Martha definitely has father issues. Her father is president of the college where her husband teaches in the history department, a sorry disappointment in that George never fulfilled the potential for which Martha had picked him—to become head of his department and eventually take her father’s place. Really, she is the one who should have done so; she, we are told, “wears the pants in the family.” But, her father has never really “seen” her. George sees that she’s the one who should have been king and he keeps her from falling into total despair.

• What is George’s core need or issue? Knight of Swords reversed.

• What is George’s core need or issue? Knight of Swords reversed.

George wields words like a sword, slashing and burning with derision, scorn and disgust all who come within his reach. A word-smith, he’s comfortable with attack and is always looking for a worthy opponent, only most of them fall far too easily beneath his sword. Martha does not.

He’s also her Knight in Shining Armor, tarnished beyond repair and, if we are to believe him, the agent of the deaths of both his mother and his father.

• What is the main theme? Queen of Cups reversed.

• What is the main theme? Queen of Cups reversed.

While many other themes can be found, this card clearly points to this one: how we hurt those we love and how little love there can be when one doesn’t love oneself. It suggests the lengths they will go in order to not feel sorry for themselves, despite being emotional wrecks.

Among other things, this theme is played out through the failure of both couples to have given birth, to have had a child—the empty, deflated womb (poof!). The card could also be a nod to the alcoholic haze they are all in.

.

• What is the central conflict?

The Chariot reversed, crossed by Death.

This is war; a horrible end is always just around the corner, the death of every supposed victory cuts off one-after-another means of escape or reconciliation. The play culminates with a fresh story, concocted by George, the botched novelist, in which he tells Martha that a telegram has been delivered informing them of the death of their son on the day before his 21st birthday. The Chariot is often seen as the son of the Empress and Emperor (3+4 = 7). That the existence of a son is just another game they play with each other doesn’t diminish the agony of a mortal wound—the seeming death of another piece of themselves and their relationship—that ultimately strips them down to the bare bones of who they are.

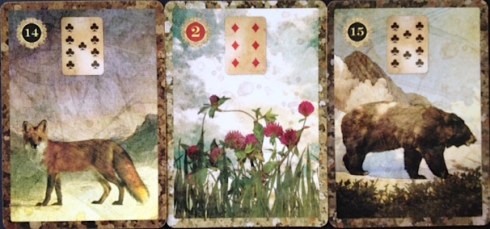

I also drew five cards from the Petit Lenormand Deck asking for a description of the plot, and I got:

Heart – Mountain – Letter – Book – Man

24-Heart: love and relationships

21-Mountain: blocks, obstacles, barriers

27-Letter: written communications, documents

26-Book: secrets, knowledge, books

28-Man: a man, the querent or significant other

This is the story of love (Heart) that has insurmountable blocks (Mountain) keeping it hidden (Book) and from being communicated (Letter). George (Man) wrote (Letter) his biggest secrets (Book) in a book that never got published (Mountain – blocked by Martha’s father). The characters are continually sending messages to each other, uncovering secrets in an attempt to touch on their true hearts that are unreachable behind the barriers they’ve erected in their disfunctional lives. As I mentioned, George (Man) is the wordsmith who is essentially composing (Letter+Book) all the scenarios (the scripts-within-the-script) to get at what is most deeply barricaded (Mountain) in each person’s heart (Heart). The Letter is also central when George claims that a telegram has arrived reporting the death of their supposed-to-be-secret son (Book+Man).

Finally, I added the numbers of these cards together and got 126, reducing it to 9-Bouquet (1+2+6=9). This stumped me at first. What could the plot have to do with a beautiful gift or invitation? Of course!—the play opens with Martha having invited the other couple over for drinks. But I was even more astounded when George mockingly presents Martha with a bouquet of flowers that he proceeds to throw at her, stem by stem.

Finally, I added the numbers of these cards together and got 126, reducing it to 9-Bouquet (1+2+6=9). This stumped me at first. What could the plot have to do with a beautiful gift or invitation? Of course!—the play opens with Martha having invited the other couple over for drinks. But I was even more astounded when George mockingly presents Martha with a bouquet of flowers that he proceeds to throw at her, stem by stem.

Before the play, I also felt compelled to look at two other cards contained within that sum of 126: 12-Birds and 6-Clouds. These were perfect to describe a play that is all about conversations (Birds) or, more properly, dialogs between two couples (Birds can also mean two or a couple) that play on deliberate misunderstandings, fears, doubts, instability, sensibilities fogged with alcohol, and confusion as to what is true and what isn’t (Clouds).

Decks: The 1910 (Pamela”A”) Rider-Waite-Smith deck. The Königsfurt Lenormand Orakelspielkarten, based on the 19th century Dondorf Lenormand (borders cut off).

Also check out my post involving reading for the movie, Beasts of the Southern Wild.

As promised, here is the information on the IndiGoGo fundraising campaign for the Waite-Trinick Tarot Book. You can help publish A.E. Waite’s Second Tarot images as quickly as possible—so we can all get them in our hands! Be part of this historic presentation.

As promised, here is the information on the IndiGoGo fundraising campaign for the Waite-Trinick Tarot Book. You can help publish A.E. Waite’s Second Tarot images as quickly as possible—so we can all get them in our hands! Be part of this historic presentation.

Tali Goodwin has started a series on her discovery of the images and the continuing saga involving her research into John Trinick. Read all about it at The Tarot Speakeasy.

A short animation by Trepaned Productions in Flash featuring music from the Portland band Polly High. Just another example of what can be done.

Music Video with RWS deck. Anyone care to explain how the reading relates to the storyline? (Thanks to John McBride.)

I thought I had this posted, but it seems not. All the “Tarot Music Videos” now have their own category—view them all by clicking on the category above or to the left.

Few things are more exciting to me than stumbling across a text or image that perfectly reflects a tarot card, especially when it makes me reconsider my ideas about that card.

Today I read the following in the mystery novel A Rule Against Murder by Louise Penny. Chief Inspector Armand Gamache, head of homicide for the Sûreté du Québec, says to a family at their annual reunion:

“We believe Madame Martin was murdered.”

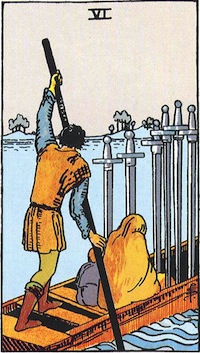

There was a stunned silence. He’d seen that transition almost every day of his working life. He often felt like a ferryman, taking men and women from one shore to another. From the rugged, though familiar, terrain of grief and shock into a netherworld visited by a blessed few. To a shore where men killed each other on purpose.

They’d all seen it from a safe distance, on television, in the papers. They’d all known it existed, this other world. Now they were in it. . . .

No place was safe.

Ah, a perfect rendition of the Six of Swords! I was first struck by it being from the viewpoint of the ferryman, not the passengers. A ferryman who is compassionately aware of the deep emotional shifts of those he is transporting—but not partaking directly in those shifts. For a moment I thought, ‘But, of course, the Six of Swords is about the ferryman, not necessarily the passengers! A ferryman who again and again observes this shift taking place in those he ferries. A ferryman who is both separate and yet momentarily involved.’

Ah, a perfect rendition of the Six of Swords! I was first struck by it being from the viewpoint of the ferryman, not the passengers. A ferryman who is compassionately aware of the deep emotional shifts of those he is transporting—but not partaking directly in those shifts. For a moment I thought, ‘But, of course, the Six of Swords is about the ferryman, not necessarily the passengers! A ferryman who again and again observes this shift taking place in those he ferries. A ferryman who is both separate and yet momentarily involved.’

There is no indication that the author, Louise Penny, had the tarot card in mind. Rather this is a common classical metaphor linking Charon and the river Styx to the family of a murdered person being ferried out of the world-as-they-had-known-it to a shore previously viewed only as a distant abstraction.

I often ask a querent, “Where are you in the card?” With the Six of Swords, the querent is always one of the figures, but it could equally be the ferryman or the hunched-over adult or the child. By contrast, with other cards, the querent occasionally sees him or herself standing just beyond the borders, behind a column, or, in the case of the Tower, still inside the structure—divorced from the action.

With the Six of Swords there is usually an eventual recognition that the querent is all three persons in the boat. As ferryman, the querent tends to feel he or she is in charge or at least doing something active that will lead to a better end. As passengers, anxiety or grief tends to trump hope, yet there is still a belief that the destination will be better than the “familiar terrain of grief and shock” that they’ve just left.

Interestingly, in the novel, the seven main suspects had, just the day before, gone out together in the lake on a boat—a passage fraught with animosity and repressed danger. The Chief Inspector/ferryman recognizes that the new world they are now facing will be more terrifying than the passengers ever could have imagined. Furthermore, they aren’t just visitors—blessed because they can leave—they will soon be inhabitants. There’s no going back. Grief and shock may exist in the land of the innocent. But, in the land of the experienced, as William Blake well knew, wrath and fear dominate, and the ferryman can’t stop it from happening. (See Blake’s Poems of Innocence and Poems of Experience.)

How different the card looks to me now. It is full of foreboding, and yet there is calm in knowing that this is an inevitable journey from the false safety of innocence into the land of Blake’s experience where realities will finally be faced. As in all murder mysteries the truth will be revealed. But, in an actual reading, is the client always ready to hear such truths?

Doesn’t the admonition, “to know thyself,” mean that we have to come to know and take responsibility for the part within ourselves who “kills another”? Both the querent and the reader want the other shore to be better than the one from which they’ve come, but there are times when we have to go through much worse. What is the reader to tell the client? And, here there are no easy answers.

I hope this makes me stop and think before I blurt out cheerfully, “Oh, you are going through a transition from the rough waters of the past to smooth waters ahead.” Sometimes I, the reader, am the ferryman/chief inspector, who must recognize with compassion that real detection can strip the soul bare and set one in the dread grasp of Blake’s tyger and not in the rejoicing vales of the lamb (see poems here). The rest of the Sword suit (7–10) warns what may come from a detection of the wrongs, or what comes to light when one really wants to “know thyself.” Does the querent really want to go there, or is the querent trusting the reader to ferry them to a safe harbor?

Still, I think it helps the reader—the ferryman who steers the way through the cards in a spread from one’s familiar anxieties to a different shore—to consider what may be truly implied from such a scene in the suit of Swords. This new perspective reminds me that in a reading I am attempting to steer the course when I don’t always know what is lying in wait for my passenger on the other side or how prepared my passenger might be to meet that. It is a grave responsibility.

I’m so excited. My Pamela Colman Smith Commemorative Tarot Set has arrived from U.S. Games. The book of Pixie’s art is delightful—full of colorful images and showing a full range of her work, including a couple of pieces from late in her life. Waite’s Pictorial Key to the Tarot (included) is the same-old book in a new cover but with no pictures (huh?). The postcards are great to have—a very nice bonus. Read the rest of this entry »

I’m so excited. My Pamela Colman Smith Commemorative Tarot Set has arrived from U.S. Games. The book of Pixie’s art is delightful—full of colorful images and showing a full range of her work, including a couple of pieces from late in her life. Waite’s Pictorial Key to the Tarot (included) is the same-old book in a new cover but with no pictures (huh?). The postcards are great to have—a very nice bonus. Read the rest of this entry »

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Recent Comments