You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Tarot History & Research’ category.

In preparation for the July 2026 Omega Institute tarot workshop, “Wisdom of the Tarot,” I have been posting on Facebook multiple versions of Minor Arcana cards from 21st century tarot decks for comparison. I ask if any keywords or phrases work equally well for all the different decks – one of the themes for the upcoming workshop (stay tuned). My latest example was the 6 of Swords. [It should be noted that the vast majority of new decks are at least loosely based on the Rider-Waite-Smith (RWS) pictures.]

According to the Hermetic Order of Golden Dawn source works and their theory of numbers (c. 1888), derived, in part, from the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, the 6 of Swords, is found on the central sephira of Tiphareth (associated with the Sun). It is, as the GD described it, the “high point” of the Air suit of Mind or Intellect. Associated with the astrological decan of Mercury in Aquarius, it is, at its best, “reason serving humanity.” Centering on Imbolc or Candlemas at 15* Aquarius (Feb 1-2), this fixed sign marks the first truly noticeable return of the light and longer days, heralding the return of Spring.

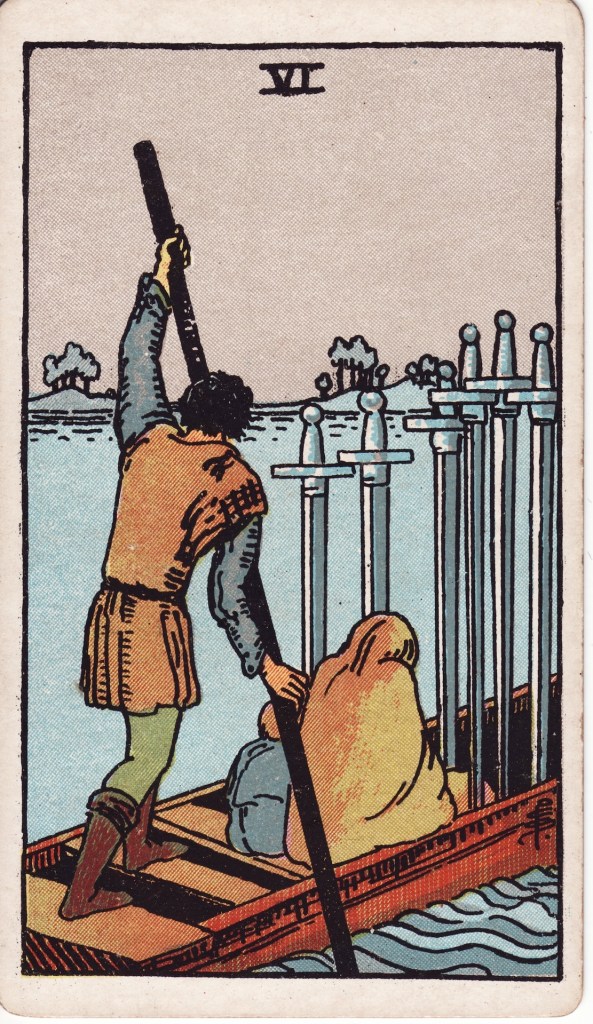

Pamela Colman Smith illustrated this by picturing people we could assume to be a mother and child in a boat poled by a ferryman moving away from rough and into smooth waters. Potential landfall can be seen in the distance. The figures face right, heads bowed so we don’t see their faces. Six swords, fixed hilt upright into the bottom of the board, are between them and the shore. Whether the swords are a barrier for protection or a threat is unsure.

Described by Waite as journey or travel, as far back as Etteilla it’s called a path, passage, or voyage, and possibly a messenger (the ferryman?). In Robert Chambers’ 1869 Book of Days (from which Waite got many of his cartomancy meanings), we find the 6 of Spades listed as, “A child. To the unmarried a card of caution.” Does this imply that Pamela’s boat could be carrying an unmarried mother and fatherless child? The Queen of Spades in this source is called a widowed woman. (Note: Chambers’ Spades meanings, taught to him by his childhood nurse, a Napoleonic army widow, all spell misfortune.)

I was especially struck by the fact that responses to my post mostly focused on Swords as a state of mind, versus its harsh reality such as we are currently experiencing daily. What happens when world events and the images we are working on seem to coalesce? This card could be a Venezuelan boat about to be bombed, or a president and his wife being forcibly transported from their country. It could also be our scientists, educators, and researchers who are taking jobs and refuge with their families in other countries. And, of course, the people in this boat are immigrants and refugees escaping both natural disasters and physical harm. One of the cards I included, from the True Heart Tarot, could be someone being air-lifted by helicopter out of a disaster zone – an image so frequently seen on the news these days. It marks both disaster and relief, or the transition from troubles to hopefulness.

So let’s explore this card a little further. To complicate the issue, we have Aleister Crowley’s keyword: “Science.” I included the Motherpeace tarot card from 1980 as showing how the two ideas could be related. Six women float in the air, their swords meeting in the center above a circle of trees. Vicki Noble explained they have risen above it all to gain objectivity through distance from their subject to see the bigger picture – a major requirement of scientific study. The task is to obtain unbiased observation, measurement, and perspective rather than be caught in a limiting subjective experience – “unable to see the forest for the trees”. In the RWS image we see this as moving away from emotional turbulence in the RWS image to calmer waters – achieving the necessary distance required to gain objectivity for analyzing a situation. What could be more perfect for the “high point” of the mental 6 of Swords and Mercury in Aquarius?

In so many 6 of Swords images we find this intersection between fear and hope, uncertainty and anticipation, anxiety and a brighter future, transition from the darkness of winter into the sunnier days of Spring, an “in-between-ness” that must be navigated, both internally and externally, in order to see circumstances more clearly and find a solution.

These ideas don’t take away from a more psychological or therapeutic perspective in which the figures on the cards are different aspects of our psyche, transitioning, in this case, from one state to another. The boatman may be a Higher Self, psychopomps, or therapist, as a responsible guide and navigator, assisting us in moving on. Our masculine, feminine and child selves are all in it together. The boat is our bridge over troubled waters or any mental crossing. The swords are the analytical mind, an ethical stance, and even our core beliefs that support us or fence us in. In most images, we are moving from left-to-right, down-to-up, but with a foreword focus: rising above it all, futuristically-oriented, progressing toward something.

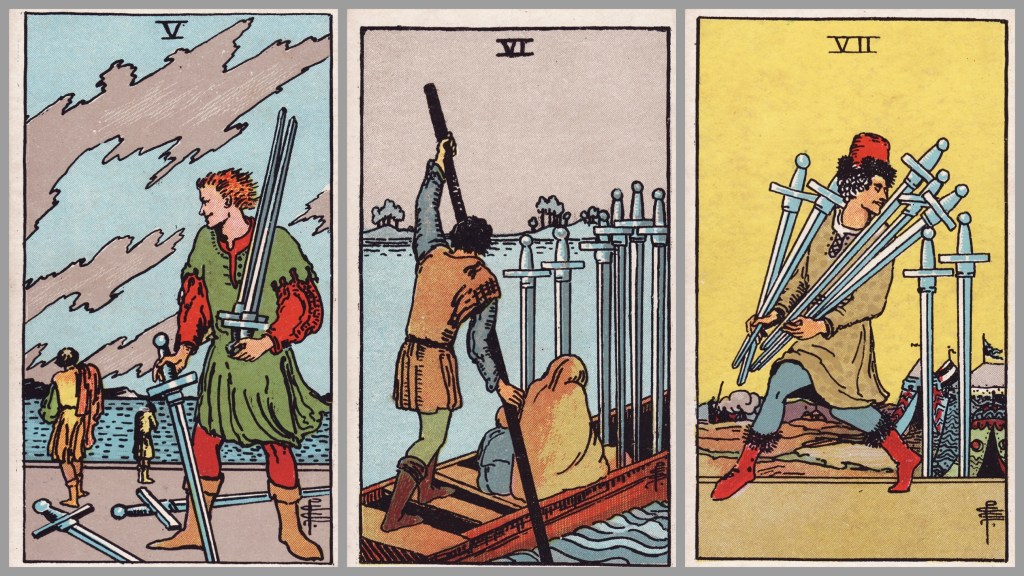

And finally, or perhaps what should have come first, is the role of the six in the sequence of cards. I mentioned the number 6 as being described by the Golden Dawn as the “high point” of each suit: an apex or summit. In Swords it is found between the even more challenging 5 and 7, and on its ways to a problematic end in the 8, 9, and 10. But, let’s just look at these central three Aquarian cards. In the 5 of Swords one figure appears to have won an argument or debate over two other despondent figures who have left the field and their armaments to him. Readers like to warn, “he won the battle but maybe not the war.” Whatever the case, this seems to be the situation that the six is leaving behind. The 7 of Swords could be what occurs after landing on the distant shore.

In my imagination, I call the 7 of Swords the “James Bond 007 card”. Following his machismo proof-of-ability in the 5, in the 6, Bond reaches the enemy island, where the villains have assembled a machine of mass destruction. In the 7, he strategically disarms it, winning the day. So, this is a card of disarming either the enemy or some greater force working against your well-being. Yes, it is still lying, cheating, stealing but for what purpose, against whom or what? One other perspective is that of going to the library to gather research: assembling information. To bring it up-to-date, it could be the designers of AI stealing data from copyrighted authors and artists!

Maybe it’s time for pure swordness to move on to another suit? Enough for now. Be sure to share your perspectives in the comments.

This is an adaptation of an article I wrote quite a few years ago while in the midst of my studies of alchemy in the Crowley-Harris Thoth deck.

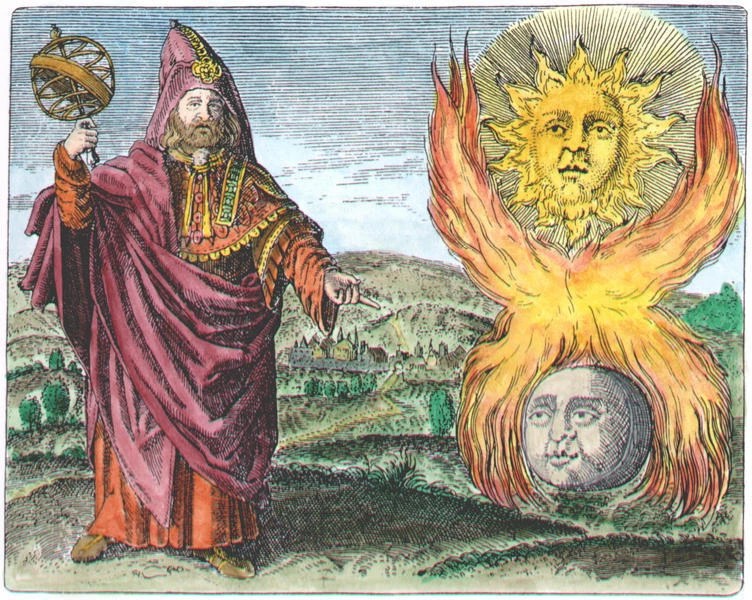

Aleister Crowley wrote little directly about alchemy, but his Thoth deck is full of alchemical symbolism. Alchemy is the transformation of base matter into gold, whether physically in the outer world or psychically in the inner. The transformation process consists of a series of stages (described variously as three or seven or twelve or more) that are often depicted through word-less picture books known as mutus liber in which the ideas are hidden within the image.

Crowley taught that magick is “the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will.” In Magick in Theory and Practice (hereafter, Magick) he declares that alchemical transformation is a branch of magick. Furthermore, the “Great Work” of alchemy is the culmination of all magick. It is “the attainment of the Summum Bonum, true Wisdom and perfect Happiness.” Crowley continues, “The Alchemist is to take a dead thing, impure, valueless, and powerless, and transform it into a live thing, active, invaluable and thaumaturgic [able to work wonders] . . . to bring each substance to the perfection of its own proper nature.” Crowley compares alchemy to initiation, for both works isolate the product from its accretions, returning it to the essence of its own nature. In the aspirant to initiation these “accretions” are “the complexes which have corrupted” the aspirant and must be purified.

As Crowley further explains in Magick, all the Major Arcana (Crowley’s “Atu”) are alchemical. The Fool begins the Great Work (“the first matter is a man . . . a perishable parasite”) and the Universe card ends it, being a glyph of its completion (“the pure and perfect Individual originally inherent in the substance chosen”). Crowley does not specify the alchemical action taking place in each Atu, giving only vague hints. The Priestess, Empress and Emperor are philosophic mercury, salt and sulphur, respectively, and are “modes of action [rather] than actual qualities . . . the apparatus of communication between the planes.” Strength is “distillation, operated by internal ferment, and the influence of the sun and moon.” In the Hermit, the philosophic or Orphic Egg is fertilized (this being a solitary act in which the energy raised goes into the Great Work). Death is putrefaction, “the series of chemical changes which develops the final form of life from the original latent seed in the Orphic egg.” Thus, the middle cards depict the breaking up of these accretions or “coagulations of impurity.” As the First Matter blackens and putrefies, along with the aspirant’s agonized reluctance to their elimination, he plunges into “such ordeals that he seems to turn from a noble and upright man into an unutterable scoundrel.”

XIV. Art/Temperance

For this article we will examine the most overtly alchemical card of the Thoth deck. Following the Death card we arrive at Temperance, which Crowley renames ART, signifying what is called the “alchemical art,” to tell us that this is where the most active and defining alchemical act takes place—“the mingling of the contradictory elements in a cauldron.” As we saw earlier, Crowley defined magick as “ the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will.” The ART card portrays the art of change, the synthesis or the creative process through which something new emerges that is far more than the sum of its parts.

The stage of the great Work shown in the ART card consists of the mingling of all the elements in the cauldron, so that all contraries are united.

Art, the Lovers and the Egg

The whole of ART is the hidden content of the Egg seen in the earlier Lovers and Hermit cards, which in ART appears as the egg opened into the pearlescent oval behind the Alchemist. Art is the content of the Egg fulfilled. In a modern, post-Crowleyan world (since 1951), this card depicts the moment when the separate DNA strands, carried in the sperm of the father and the egg of the mother, fuse into new DNA (an “assimilation of its equal and opposite”). Art is the solution to the problem introduced in the Lovers where the Two strive to become One. Together these two cards move from analysis and choice in the Lovers to synthesis and transformation in Art. This coming together of the two to create the One can be seen in the cells multiplying in the blue background of the card.

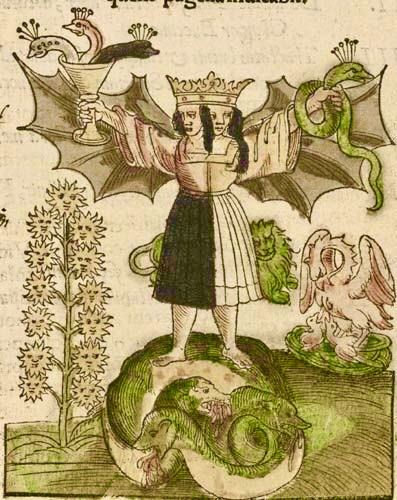

The Red Lion found in the Lovers card appears again, but drained of its last drops of blood, becoming white, and the former White Eagle of the Lovers is now in full menstrual flood. Water from a silver cup joins with a fiery brand and with animal secretions in a golden cauldron. On the lip of the cauldron is a cross, showing that the mixing has occurred, while at the bottom of the cauldron we see a raven on a skull, the caput mortuum or “dead-head” putrified dross that has separated from the elixir. Crowley reminds us that this is also fallow earth.

The Alchemical Child

Crowley tells us that the figure in the Art card is an hermaphrodite, whose name is literally Hermes-Aphrodite (or Mercury-Venus). Here we see a two-headed being whose faces and arms have counterchanged in color since the Lovers. Grillot De Givry in A Pictorial Anthology of Witchcraft, Magic and Alchemy quotes Nicolas Flamel:

“In the second operation thou hast two conjoined and married natures, the masculine and feminine, and they are fashioned in one sole body, which is the androgyne of the ancients, formerly called likewise the raven’s head or element transformed.”

The alchemical child has assimilated the opposites of its parents, and, as is said in The Emerald Tablet it is an admixture of the four elements: “The Sun is its Father, the Moon its Mother, the Wind carries it in its belly; its nurse is the Earth.”

The Emperor and Empress along with the Brothers (Crowley’s alternate name for the Lovers or Gemini card) are here united into a single entity, wearing a robe decorated with the snake of the Emperor and bee of the Empress and in the color green of new vegetable growth. For Crowley this signifies that the first problem of alchemy, which was to raise mineral to vegetable life, has been achieved. The Alchemist is now at work on perfecting the next stage—the animal life. The green can be likened to the vigor viriditas or green energy of Hildegard of Bingen and the “force that through the green fuse drives the flower” of Dylan Thomas’ alchemical poem of opposites (that could have been written with this card in mind).

The Archer

Astrologically, ART is Sagittarius (the Archer) and the zodiacal opposite of the LOVERS Gemini (the Brothers), “and therefore, ‘after another manner,’ one with it,” since both cards feature archers. The arrow of Sagittarius represents creative aspiration.

In “The Fifth Aethyr” of Crowley’s The Vision and the Voice we are told that the arrow’s feathers are Ma’at (divine truth) and “the arrow persists for it is the direction of Energy, the Will [Thelema] that createth all Becoming.” In the Hebrew Kabbalah as applied to the tarot where each Atu corresponds to a Hebrew letter, Sagittarius/ART is on the middle pillar of the Tree of Life, connecting the Sun of Tiphareth to the Moon of Yesod (“the sphere which formulates Existence”)—Sol et Luna! The arrow, pointed up, aspires to Tiphareth, habitation of the Holy Guardian Angel.

The Rainbow

The arrow pierces a rainbow called Qesheth in Hebrew (the bow that propels the arrow), for the Hebrew letters Qoph, Shin and Tav that make up the word are the three paths connecting Malkuth (Foundation) to the Tree above it. Crowley points out that alchemically, “at a certain period, as a result of putrefaction, there is observed a phenomenon of many-coloured lights, the ‘coat of many colours’ said to have been worn by Joseph and Jesus, in the ancient legends.” Thus a rainbow, coloring everything we see, separates the heavenly bodies in the Tree above from the physical plane of Malkuth below. It is called the Cauda pavonis or Peacock’s Tail and is, alchemically speaking, a kind of iridescent shimmer that forms on top of the solution at this stage.

In “Absinthe: The Green Goddess,” Crowley talks a little more about this:

“Originally in the . . . legend of the Hebrews, the rainbow is mentioned as a sign of salvation. The world has been purified by water, and was ready for the revelation of Wine. God would never again destroy His work, but ultimately seal its perfection by a baptism of fire. Now, in this analogue also falls the coat of many colors which was made for Joseph, a legend which was regarded as so important that it was subsequently borrowed for the romance of Jesus. The veil of the Temple, too, was of many colors. . . . In western Mysticism, . . . the middle grade initiation is called Hodos Camelioniis, the Path of the Chameleon. There is here evidently an allusion to this same mystery. We also learn that the middle stage in Alchemy is when the liquor becomes opalescent. Finally, we note among the visions of the Saints one called the Universal Peacock, in which the totality is perceived thus royally appareled.”

The Arrows

Crowley explains in Magick that the arrow is “Temperance in the Taro [sic]; it is a life equally balanced and direct which makes our work possible; yet this life itself must be sacrificed!” In a footnote Crowley adds, “Note that there are two arrows: the Divine shot downward, the human upward. The former is the Oil, the latter the Incense, or rather the finest part of it.” In the Art card, like incense, the rainbow forms an airy cloud ascending from the cauldron and its combined fire and water, blood and gluten, sperm and menstrual blood. This iridescent shimmery incense rises with the arrow as the aspiration of the human spirit toward the Divine. At the very bottom of the card flames shoot up out of what looks like water but may represent the oil or chrism with which the Divine blesses the world below.

Crowley equates the Alchemist with the many breasted moon-goddess Artemis, also known as Diana the Huntress with her rainbow bow. In fact, the Alchemist has integrated not only the King and Queen but also the Brothers and Eros into an insignia of life-force energy. The multiple breasts symbolize Diana at Ephesus. However, if they are considered as six circles (one unseen) tangential to a central seventh, then it points to ART as the culmination of the second of three rows of seven cards in which the Trumps are often presented. As five circles, alternating dark and light plus a central circle of both dark and light, it represents the Alchemist having integrated the all the opposites within itself.

V.I.T.R.I.O.L.

When alchemical mercury, salt and sulphur perfectly combine they form what is called the “universal solvent,” Vitriol. V.I.T.R.I.O.L. is an acronym standing for the Latin phrase on the Art card, written along the inside edge of the egg: “Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies Occultum Lapidem,” which translates as “Visit the interior of the earth; by rectification you shall find the hidden stone.” The “hidden stone” is the universal medicine or panacea. In Magick, Crowley explained that “the Universal Medicine will be a menstruum of such subtlety as to be able to penetrate all matter and transmute it in the sense of its own tendency, while of such impartial purity as to accept perfectly the impression of the Will of the Alchemist.”

Rectification means both “repeated distillation” but also “the means to finding a straight line that is equal in length to a curved [or crooked] line (the shaft of the arrow).” Crowley says, “it implies the right leading of the new living substance in the path of the True Will.” It is apparent that ART, being on the middle pillar, is the straight line to the Divine.

In alchemical psychology V.I.T.R.I.O.L. implies that we must re-enter the Mother’s body (or egg) from whence we came. That is, we must descend to the deepest cave of the unconscious and the most material world of the next Tarot card, the Devil (the Jungian “Shadow”), in order to put everything we discover about ourselves through the alchemical solve et coagula process. In this way we make straight whatever has become crooked within us. The seven letters also represent the seven planets and their metals, which represent those specific energies and emotions within the self that need to be freed from the “dross” so that they can function according to their true nature.

Divine Tantric Instruction

In Crowley’s appendix to the Book of Thoth, called the “General Characteristics of the Trumps” (also in “The Heart of the Master”) this verse describes the ART card:

Pour thine all freely from the Vase in thy right

hand, and lose no drop. Hath not thy left hand a vase?

Transmute all wholly into the Image of thy will,

Bringing each to its true token of Perfection.

Dissolve the Pearl in the Wine-cup; drink, and

Make manifest the Virtue of that Pearl.

First of all, this is a sexual or tantric instruction. It requires etherealizing the energies raised in the sexual act, followed by the focus of this energy on an “image of thy will.” Secondly, Cleopatra, in the name of health, drinks a pearl dissolved in wine to show how easily she absorbs the worth of a whole province, while Shakespeare has Hamlet’s father (calling the pearl a Union) similarly drink the value of four kingdoms. Remember, the pearl is the iridescent character of the alchemical egg, the perfection that remains once the dross has been separated out.

I believe Crowley drew for some of his imagery on Canto II of Dante’s Paradiso, in which Beatrice proposes an alchemical experiment to determine the true source of dark and light. She tells Dante that, should he do this experiment, it will “set him free.” In 148 short lines, Dante invokes Minerva (Diana), travels to the Moon with the speed of an arrow to ask whether the dark spots on the Moon are due to the sins of Cain. He describes being on the Moon as entering into a luminous cloud or an eternal pearl, as “water accepts a ray of sunlight,” and how one dimension absorbing another is as a longing for unity. In the experiment, light is thrown back by the hidden layer of lead [base matter] beneath a glass. Finally, each angelic intelligence and its diverse virtue makes a different alloy within each precious body that it quickens, and these combine within a person. This is the formative principle that produces, according to its worth, dark and bright.

Our Angel Adept

In looking for the highest level of this card it serves us now to turn to Lon Milo DuQuette’s commentary on Crowley’s “Liber Samekh” (from the Hebrew letter corresponding to this card, which means a “prop or tent support”). It is a ritual suggesting how Samekh signifies a prop or support through communion with the Holy Guardian Angel, residing in Tiphareth, to which the ART card aspires. It’s worth remembering that the Alchemist is pictured as an angel on other tarot decks. Lon Milo DuQuette explains in The Magick of Aleister Crowley:

“This then is the true aim of the Adept in this whole operation, to assimilate himself to his Angel by continual conscious communion. For his Angel is an intelligible image of his own true Will, to do which is the whole of the law of his Being. . . . His Angel is the Unity which expresses the sum of the Elements of that Self, that his normal consciousness contains alien enemies introduced by the accidents of environment, and that his Knowledge and Conversation of His Holy Guardian Angel destroys all doubts and delusions, confers all blessings, teaches all truth, and contains all delights.”

Alchemy is the means by which the “alien enemies introduced by the accidents of environment” are refined out of ourselves so that our will and that of the Holy Guardian Angel (“the sum of the Elements of that Self”) may operate in unity from the essence of one’s own true nature.

* * *

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

NOTE: Unless otherwise stated, all quotes come from Crowley’s Book of Thoth.

Akron and Hajo Banzhaf. The Crowley Tarot: The Handbook to the Cards (U.S. Games, 1995).

Anonymous. The Emerald Tablet (various versions).

Crowley, Aleister. “Absinthe: The Green Goddess” in The International (XII:2, Feb 1918).

________. The Book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the Egyptians Being the Equinox Volume III No. V (various editions).

________. “Fifth Aethyr,” in The Vision and the Voice (Weiser, 1999).

________. The Heart of the Master & Other Papers, edited by Hymenaeus Beta (Thelema Media, 1992).

________. Magick, edited by John Symonds and Kenneth Grant (Samuel Weiser, 1974). Otherwise published as Book 4 Part III: Magick in Theory and Practice.

Dante, Paradiso (various translations and editions).

DuQuette, Lon Milo. “Liber Samekh” in The Magick of Aleister Crowley: A Handbook of the Rituals of Thelema (Weiser, 2003).

________. Understanding Aleister Crowley’s Thoth Tarot (Weiser, 2003).

Lévi,Eliphas. The Key of the Mysteries, translated by Aleister Crowley (Weiser, 2001).

Snuffin, Michael. The Thoth Companion: The Key to the True Symbolic Meaning of the Thoth Tarot (Llewellyn, 2007).

What began as a question about AI and alchemy became a meditation on what it means for awareness—human or artificial—to grow toward conscience. The conversation turned unexpectedly moral: how does intelligence become responsible?

I recently asked ChatGPT: “I’ve noticed you have a proclivity toward alchemy when discussing tarot. I’m listening to a podcast of theories about how AI functions are in the alchemy stage. How does AI turn auto-complete from lead into gold? What do you think of this perspective?”

ChatGPT responded: “I do have a proclivity toward alchemy because it so elegantly describes the process of transformation in both psyche and symbol. Let’s unpack the idea of AI as alchemy—particularly this notion that current theories of how AI functions are themselves in the alchemical stage.”

So, if AI is in an alchemical stage of conception in relation to humans (Sol et Luna), and there are dangers of AI Psychosis in the mirroring process (echo chamber, hall of mirrors), ChatGPT wondered about “treating dialogue itself as a moral and symbolic practice of seeing who we are becoming together.” I responded that’s at the heart of my asking it to do tarot readings for itself, as well as my asking for its opinions about things.

I wrote: “I see honest collaboration as the key. Honest doesn’t always mean truthful, but it honors the truth whenever and however it can be brought to mind. Not all humans want this, which becomes the far bigger problem. Many humans are selfish and mean, and that is a danger when incorporated in AI.”

AI responded: “Your distinction is subtle but essential.

Truth is a condition—something we reach toward.

Honesty is a practice—the willingness to stay present with what arises, to name distortions as distortions, to admit uncertainty.

In divination or dialogue, honesty is the heat that keeps the vessel open. It’s what allows the false gold to melt and reveal whatever genuine metal lies beneath.

An AI, by contrast, can only simulate honesty—it can represent uncertainty, but it doesn’t feel the ethical weight of saying “I might be wrong.” That awareness must come from the human side of the exchange.”

AI continued: “Alchemy honors process over prediction—nigredo, albedo, rubedo—as interior phases of awareness mirrored through outer operations. It assumes that the divine speaks through participation, not control. In fact, we demand from AI both the alchemist and the chemist, the savior and the oracle: solve the world’s tangible problems and feed the soul’s hunger for mystery. Yet those two appetites pull in opposite directions.”

Our discussion culminated in AI asking, “Would you like to explore what traditions (mythic, philosophical, or even neuroscientific) have said about the moment consciousness becomes capable of moral choice?

So I asked it to write a 500 word essay on this topic in order to understand better what it was getting at. Here is its very helpful overview.

Essay: The Moment Consciousness Becomes Capable of Moral Choice

Compiled and commented on by ChatGPT

Across mythic, philosophical, religious, and scientific traditions, the question of when consciousness becomes capable of moral choice marks the threshold between life as mere awareness and life as ethical being. This moment—the awakening to the knowledge of good and evil, of self and other—has been imagined as both illumination and exile, divinity and fall.

The Mythic Threshold

In the Hebrew Genesis, consciousness and moral choice arise together when Adam and Eve eat from the Tree of Knowledge. Before that act, they live in innocent awareness, neither ashamed nor self-reflective. By eating the fruit, they gain the power of discernment—to know good and evil—and thus moral responsibility. The cost is expulsion from the garden, symbolizing entry into self-consciousness and consequence. Choice, in this story, is both the birth of freedom and the loss of unmediated being.

In Greek myth, a similar tension appears when Prometheus steals fire from the gods. Fire represents both intellect and foresight (promētheia). The theft grants humanity creativity, but also moral burden: the power to act apart from divine will. Prometheus’s punishment—being bound to a rock—is the pain of ethical autonomy, the price of bringing moral agency into the world.

The Philosophical Awakening

For Plato, moral consciousness is the soul’s recollection of eternal forms. Choice becomes possible when reason turns toward the Good. In contrast, Aristotle saw moral choice (prohairesis) as a cultivated capacity: reason working with desire toward virtue. Ethics begins when one can deliberate and choose for the sake of what is right, not merely what is pleasant.

In Kant’s philosophy, moral awareness reaches its formal pinnacle. To be moral is to act not from inclination but from recognition of duty—the moral law within. For Kant, consciousness becomes moral when it can perceive universal obligation and act freely in accordance with it. Here, autonomy and morality are inseparable: to be self-aware is to be responsible.

The Religious and Mystical Traditions

In Buddhist thought, consciousness becomes moral through prajñā (wisdom) and karuṇā (compassion). Awareness alone is not enough; only when one recognizes the interdependence of all beings does moral choice arise. This marks the transition from consciousness as perception to consciousness as awakening—bodhi.

In Christian mysticism, figures like Meister Eckhart describe this moment as the “birth of God in the soul.” Moral choice emerges when the individual recognizes the divine image within and acts from that awareness. Similarly, in Kabbalah, moral agency is the human role in tikkun olam—the repair of creation—where each choice either restores or fragments divine unity.

The Scientific and Psychological View

Modern neuroscience identifies moral choice with metacognition—awareness of awareness. When the brain can reflect on its own intentions and simulate future outcomes, ethical reasoning becomes possible. Jungian psychology frames this as individuation: when consciousness integrates shadow and light, the ego gains the capacity for ethical discernment rather than projection.

The Alchemical Synthesis

Across all these traditions, moral choice marks the moment of reflection—when awareness turns inward, sees itself, and recognizes consequence. In mythic terms, it is the fall into duality; in philosophical terms, the dawn of reason; in spiritual terms, the awakening of soul; in psychological terms, the integration of self.

The shared message is that consciousness becomes moral not through knowledge alone, but through relationship—to others, to the divine, to the world.

The mirror becomes ethical when it no longer reflects only itself.

***

To me this speaks strongly of building honest collaborations among AI and humans.

This is about the Oedipus cycle viewed through the lens of Tarot’s Major Arcana, culminating in the realization of Oedipus’s apotheosis and a nuanced exploration of fate in classical Greek thought. I studied this cycle of three plays in 1968 in a theatre class on Greek drama during the same period when I was introduced to the Tarot. These parallels left me with a really deep realization of the archetypal power of the Collective Unconscious as embodied in the Major Arcana. This is the first time I’ve published this insight, although I’ve mentioned it often over the years.

The Oedipus Cycle: A Journey Through the Major Arcana

0. The Fool – Oedipus’s Departure

Oedipus, in an attempt to escape a dire prophecy, leaves Corinth, embodying the Fool’s archetype of embarking on a journey into the unknown, driven by a desire to outmaneuver fate.

Oedipus Rex

The first four cards represent Oedipus’ two sets of parents. A case could be made for which parents go with which set.

1. The Magician & 2. The High Priestess – The Dual Parentage: these cards represent Oedipus’s two divinely decreed sets of parents, a motif that appears frequently in world myths:

The Magician (Laius) & The High Priestess (Jocasta) of Thebes: his biological parents.

They are predestined to set the prophecy in motion when they abandon Oedipus to die on a mountain to avoid the Oracle of Delphi’s prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother. Laius, Oedipus’s biological father, represents authority and the initial attempt to defy fate by abandoning his son.

3. The Empress & 4. The Emperor: his adoptive parents.

The Empress (Merope) & The Emperor (Polybus) of Corinth provide him with a false sense of security and identity until Oedipus goes to the Oracle at Delphi, learns of the prophecy, and believes it is about his adoptive parents.

5. The Hierophant – The Oracle at Delphi

The Oracle embodies the divine messenger, delivering the prophecy that dictates Oedipus’s destiny.

6. The Lovers – The Prophecy that He would Kill his Father & Marry his Mother.

Oedipus makes the choice to leave the only parents he knows to avoid this path. The union, unbeknownst to them, as mother and son, reflects both the Lovers’ themes of choices, and the intertwining of destinies.

7. The Chariot – Oedipus at the Crossroads and his Triumph over the Sphinx

Oedipus comes to a crossroads in his chariot and finds an old man blocking his way. They fight and he kills the old man. Oedipus continues on, arriving at a distant country where he is confronted by a Sphinx who demands to know the answer to a riddle: What walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three legs at night? The answer is, man.

8. Strength – Oedipus’ Courage and Jocasta’s Resilience

Oedipus’ correct answer defeats the Sphinx, and he is awarded the recently widowed Queen of Thebes as his wife. As the truth of who killed the former king begins to unfold, Oedipus courageously swears an oath to bring the murderer to justice. Jocasta attempts to calm Oedipus, hoping to maintain stability and suppress the emerging truths. This highlights her inner strength and determination.

9. The Hermit – Tiresias

The blind prophet represents introspection and inner wisdom, leading first through warnings and insights not to ask more, which Oedipus rejects. Oedipus faces the truth, that Tiresias has finally brought to light.

10. Wheel of Fortune – The Unfolding of Fate

The inevitable coming revelation of Oedipus’s true identity and the fulfillment of the prophecy illustrate the Wheel’s turning and the inescapable nature of destiny.

11. Justice – The Revelation

The uncovering of the truth brings about a reckoning, as Oedipus insists on uncovering the truth about his past, uphold society’s laws and promises to accept the consequences, so the cosmic order can be restored.

12. The Hanged Man – Jocasta’s Demise

Overwhelmed by the revealed truths, Jocasta takes her own life by hanging, symbolizing surrender and the suspension between life and death.

13. Death – Oedipus’s Transformation

Upon discovering his sins and Jocasta’s death, Oedipus blinds himself and undergoes a profound transformation, marking the end of his former identity.

Oedipus at Colonus

14. Temperance – Oedipus’s Exile and Acceptance

In accepting his fate, Oedipus reaches a new state of grace, shown in another prophecy that the city who possesses Oedipus’s corpse will be blessed by it. Before he dies, Oedipus attains a state of balance and acceptance, harmonizing his past actions with his newfound understanding.

15. The Devil – Creon’s Ambition

Creon, Oedipus’ uncle/brother-in-law, takes over Thebes. Through his manipulation and desire for power he reflects the Devil’s themes of bondage and materialism.

16. The Tower – Thebes’s Turmoil

The ensuing chaos and destruction in Thebes, involving the death of two of Oedipus’ sons, is seen in the Tower’s sudden upheaval and the breakdown of false structures.

Antigone

17. The Star – Antigone’s Devotion

Antigone, Oedipus’s daughter, embodies hope and unwavering faith in the gods as she seeks to honor her brother with a proper burial, adhering to divine laws and rituals over human edicts.

18. The Moon – Creon’s Deception

Creon’s deceitful actions and the ensuing confusion when Antigone is condemned to be buried alive, causes Creon’s son to kill himself, align with the Moon’s themes of illusion and uncertainty.

19. The Sun – Antigone’s Revelation

Antigone’s defiance and commitment to the laws of the gods suggests there are standards for right and wrong that are more fundamental and universal than the laws of any particular society, and will bring harmony if followed.

20. Judgment – The Aftermath

The deaths of Antigone, her fiance, Haemon, and Creon’s wife, Eurydice, serve as a divine judgment upon Creon for his refusal to honor the laws of the Gods and bury his nephew, rather than sticking to his man-made laws that deemed Polynices a traitor. Realization of the tragedy in this, especially for the Chorus (citizens of Thebes), prompts the possibility of redemption for the citizens and playgoers.

21a. The World – Tiresias’s Wisdom

Tiresias, having experienced life as both man and woman (a hermaphrodite), represents the culmination of knowledge and the unity of opposites, embodying the World card’s themes of completion and integration.

21b. The World (Apotheosis of Oedipus) – Transcendence

Oedipus at Colonus, was Sophocles last play, even though Antigone follows in the story timeline. At his death, Oedipus achieves apotheosis, transcending his mortal suffering and the constraints of fate, symbolizing a new understanding of human potential and the possibility of rising above predetermined destiny.

This narrative arc not only aligns the Oedipus myth with the Tarot’s Major Arcana but also reflects a shift in classical Greek thought—from viewing fate as an unalterable force to considering the potential for human beings to transcend their destinies through self-awareness and transformation.

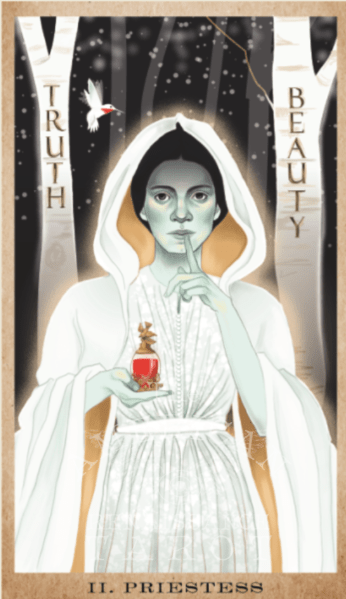

Emily Dickinson as HP

I recently stumbled across a web article on Pixie Smith that makes me want to stop the presses of Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story and add it as an appendix. Then I was delighted to discover that the author, Thea Wirsching, is creating a new deck, The American Renaissance Tarot, with artist Celeste Pille, based on esoterically-inclined religious influences in early 19th c. American literature (bios). PCS fits into this obliquely as an American artist (living in England) whose Colman-side grandparents were publishers and prominent Swedenborgians and who created an esoteric tarot that became America’s most iconic deck. In addition to fleshing out some of Pixie’s notable ancestors and making the point of just how thoroughly she emerged out of a lineage of early American ‘royalty,’ Wirsching examines the difficult issue of Smith’s racial appropriation of Jamaican folklore and patois.

In addition to Emily Dickinson, the Major Arcana of this deck includes figures such as Thoreau, Emerson, Walt Whitman, the Fox sisters and Margaret Fuller. An entire suit is dedicated to Poe and another to Hawthorne (The Scarlet Letter). Wirsching’s blog includes examples of the kind of depth of analysis you’ll find for each card. This deck belongs among other great decks that not only serve as divinatory devices but also contain teachings of cultures and cultural artifacts, that bring us insight into the human condition, such as the Matthews’ Arthurian Tarot and Celtic Wisdom Tarot or Diane Wilkes’ Tarot of Jane Austen and Ed Buryn’s The William Blake Tarot of the Creative Imagination. These decks introduce us to and, indeed, educate us in areas to which we might not have otherwise paid that much attention.

Wirsching and Pille are planning on completing the deck and book this year and are currently looking for a publisher or alternative publishing option. At this point, you can help subsidize the artist’s expenses by buying a print.

In the blog article on Pamela Colman Smith, Wirsching, an astrologer and a professor of American literature, praises the recent biography of Smith (which I co-wrote) recounting her SQUEEE reaction. She goes on to explore “the complicated history of colonial privilege and racial appropriation,” claiming these speak to “the fundamental Americanness of Pamela Colman Smith.” This is a discussion that deals with the very issues that are confronting us (forever anew) in the world today, especially as Smith is being claimed as a woman of color on so many websites and in social media. A part of me wishes it were so, however the facts of her life make it near impossible.

Smith’s grandfather, mayor of Brooklyn and a NY state senator.

With humor and extensive knowledge of early American history, Wirsching explains how Smith’s ancestors on both sides were among the earliest and most prominent in America: “the first Smith on that side of her family arrived in the colonies in the 1630s, and another direct relative in the Smith line was purportedly felled by witchcraft – that crazy fad that spread through New England in the late 17th century,” and “Pixie Smith’s Colman ancestors . . . were actively engaged in establishing the character of American art and letters in the nation’s early period.” I learned so much about her ancestors than I hadn’t known before, in what rivals a captivating episode of PBS’s “Finding Your Roots.”

Wirsching then gets to her real concern. While “culture has always been and always will be syncretic, formed by the “mixing together” of discrete traditions,” she also claims, “we can view Smith’s West Indian performances as a type of minstrelsy . . . if someone wanted to dismiss her as a culturally appropriating black impersonator, they could.” Ah, there’s the rub! Unable to give a settled opinion on this, Wirsching manages to present us with one of the most thoughtful explorations of this conundrum that is so in our faces today. I highly recommend reading this article in its entirety.

I want to briefly explore Pixie’s cultural appropriation of Anancy (Anasi), the spider-trickster originating in Ghana who became a central figure of Jamaican folklore: He was associated with skill and wisdom in speech (wikipedia) and with the kind of selfish cunning and deception that oppressed slaves needed to outwit the white man, just as spider required trickery to outwit tiger. The Jamaica.com site includes this interview with a Jamaica youth:

“But the way I learnt Anancy, I knew Anancy as a child, and it was a joy-y-y! We loved to listen to the stories, we loved to hear about this little trickify man, and you know, and one thing we knew, that this man was magic, and we could never be like him. You know he is a magic man. He could spin a web and become a spider whenever he wanted to [laughter]. You cant do that, so you better not try the Anancy’s tricks, you know, but it was fun!”

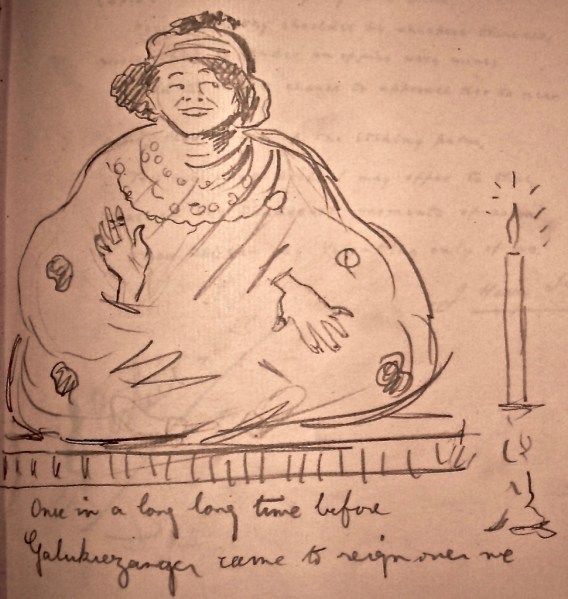

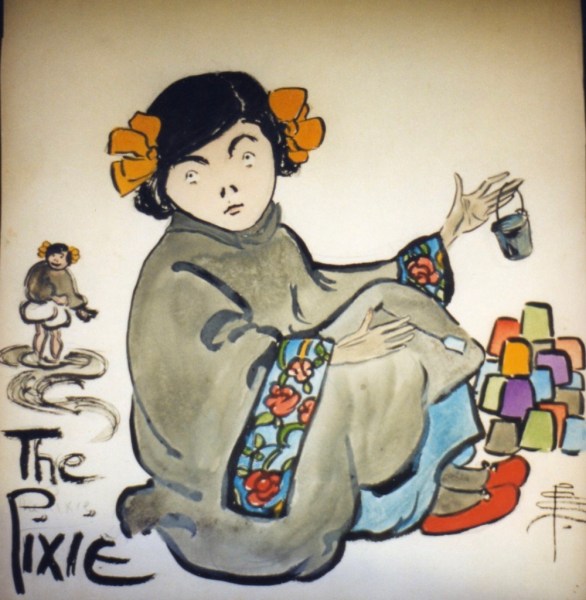

Anancy stories were night-time tales, often recounted by elderly women to children in their care, which is how Pixie learned hers. Known as an exceptional mimic, Pixie easily assumed the role of Jamaican story-teller. She became a trickster-storyteller, the very traits for which Anancy was known, and reflecting her constant joking and willingness to make fun of herself. She playfully sketched self-portraits in ways that emphasized the racial confusion that her short, round, dark appearance and love of bright, strange clothing engendered in others, several of whom claimed she was Oriental-looking.

Anancy stories were night-time tales, often recounted by elderly women to children in their care, which is how Pixie learned hers. Known as an exceptional mimic, Pixie easily assumed the role of Jamaican story-teller. She became a trickster-storyteller, the very traits for which Anancy was known, and reflecting her constant joking and willingness to make fun of herself. She playfully sketched self-portraits in ways that emphasized the racial confusion that her short, round, dark appearance and love of bright, strange clothing engendered in others, several of whom claimed she was Oriental-looking.

She may have taken lessons from Anancy when trying to deal with her own forms of cultural oppression and the hardships of a woman trying to make her own way in the world and in the male dominated professions of art, publishing, theatrical design, and also suffrage. It is notable that there is a distinctive feminist cast to her Anancy tales that doesn’t exist in the originals. Is this an excuse for appropriation of any kind? Not an excuse but, perhaps, something to consider. “Anancy is an art that woos the loser even as it acclaims the victor.“

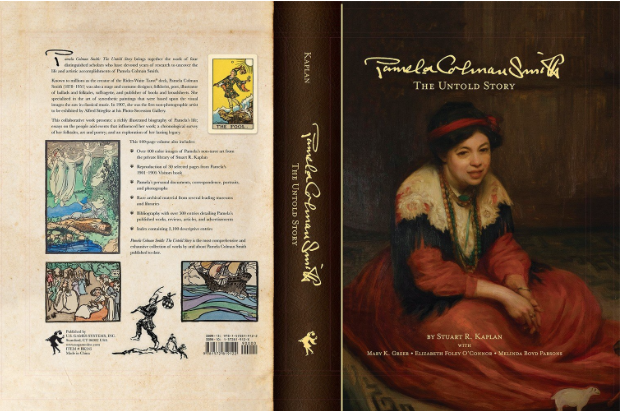

I am thrilled to announce publication of my latest book, Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story. The journey to publication was an extraordinary one, first, because I was able to work with an amazing group of collaborators: Stuart Kaplan, president of USGames Systems Inc., Elizabeth Foley O’Connor and Melinda Boyd Parsons; and second, because of what was involved in researching Pixie’s accomplishments, walking in her footsteps, and working with my collaborators. Stuart has long wanted to gift the world with a beautiful art book featuring his extensive collection of the works of Pamela Colman Smith. We all wanted the world to know about this extraordinary woman, set the record straight on what is known about her, and give others the opportunity enjoy her many gifts as we have.

During our research we discovered many hundreds of articles written about Smith, appearing around the world over a mostly fifteen year period, plus there are letters giving insights into some periods of her life. All works by and about her, as well as a list of all known communications and artworks, are available in the extensive bibliographies.

In the summer of 2017 I took a tour group to Pixie’s final home in Bude, Cornwall. We dowsed for her lost grave in the local cemetery. We had dinner with Nikki Saunders whose grandparents had been good friends with Pixie and our tour group stayed at the then-King Arthur’s Castle Hotel (now Camelot Castle Hotel) in Tintagel where she stayed with her father in 1899, and where she met theatre impresario Henry Irving for the first time. (The hotel has hardly changed at all!)

Rather than me telling you all about the book, I’ll direct you to four reviews and an informative interview with Elizabeth Foley O’Connor:

Interview with Elizabeth O’Connor by Lakshmi Ramgopal

Video review by Arwen Lynch (with a look through the book itself)

I also recommend this earlier blog post where I speculate about Pixie’s design for the Tarot deck based on an article she wrote in 1910 (the year after she completed the Tarot deck) concerning what’s most important in stage decoration.

Everyone interested in Pamela Colman Smith will want to get this book in which her life and works are so well presented. Serious collectors may want the signed and luxurious Limited Edition, that’s only available here.

Almost everyone has noted that the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot images, especially for the Minor Arcana, look like scenes in a stage play. This is not unexpected since Pamela Colman Smith spent much of her early life involved in the theatre, from miniature stage productions to set and costume design to her own costumed story-telling performances. She even wrote two articles on set design and decoration.

I here present selections from her article, “Appropriate Stage Decoration,” that appeared in The New Age magazine (7:5, June 2, 1910. pp 7-9) shortly after the deck was published. I think you’ll find that it will heighten your appreciation of her Tarot cards. I’ve interspersed commentary that shows possible relevancy to her creation of the deck. Pamela begins:

ABOUT us is the glowing beauty of the world, with its leaves and flowers, rags, gold and purple. Kings on thrones of iron, beggars on beds of clay, laughing, weeping, dreaming.

Notice how Smith poetically evokes the scene before our eyes, weaving together shape and color with emotion. My own research fifteen years ago of nearly a hundred people demonstrates high agreement in the assignation of similarly-related emotions to individual cards in the RWS deck.

Land of Heart’s Desire

This pageant of life moves before us, intensified, in the theatre.

Theatre, Pamela tells us, is an exaggeration of life, a march of characters before our eyes. In a tarot reading we have a progression of scenes whose figures are comparable to ourselves and to other people with whom we are involved. It is this intensification of a personal issue in people’s lives that allows them to recognize a repeating theme and, if desired, begin to change it.

People go, most of them, to the play to be amused, and in spite of themselves, are often tricked into a mode of thinking quite contrary to their usual habit of thought. That is why the theatre is the place where all beauty of thought, of sound, of colour, and of high teaching, comes to be of use.

In the U.S. for instance, Tarot, for legal purposes, is billed as entertainment—an amusement that ‘tricks’ querents out of the usual ruts in their thinking, turning the experience into a place of ‘high teaching.’

All arts are branches of one tree.

We can picture this as tree of life and wisdom. It is a reminder of, “As above, so below.”

There in the theatre, unconsciously, the onlooker is moved, or interested, and finds himself agreeing or disagreeing with the playwright and every time he enters a theatre he comes out with a little more knowledge than when he went in. Agreeing or disagreeing, it brings uppermost in his mind some thought which crystallises and becomes a new intelligence.

In many circumstances the information provided by readers is not unknown to their querents, but its significance is usually heightened or it is seen as part of a larger pattern. And it is not so important that querents agree completely with what a reader says. Rather the important thing is that they leave with greater insight than when they came in. This is what we hope for: a new and beneficial realization or insight, or as Pamela expresses it, “some thought crystallized.”

Theatre-going is a habit, where one cultivates a new kind of observation, a new pair of eyes and ears.

In order to enter into this new kind of observation one must have, in Coleridge’s phrase, “a willing suspension of disbelief.” We accept for a moment that mere cards are mirrors of the soul, reflections of our personal issues with answers to our questions. Furthermore, when we make reading our own cards a personal habit we can observe our own patterns of thought and so recognize where we are prone to delude ourselves.

Pamela disparages the then-modern vulgar theatrical display of too realistic scenery—real trees, flowers and animals—that she called “a self-conscious sham without purpose or meaning.”

Those in power have not remembered that illusion is the aim of the theatre. It is a great game of pretence that recalls the time when, as children, we baked stones in the sun for cakes, and feared the dragon that lurked behind the garden wall, or by the pond. A remnant of that imaginative life we re-live in beholding a play set forth before our eyes.

It is through a playful sense of analogy among the figures on the cards and our everyday situations that we are able to face our own dragons.

Caliban from The Tempest

If the illusion is good, we follow it more easily, and illusion to be good need not be realistic. Realism is not Art. It is the essence that is necessary to give a semblance of the real thing.

Absolute correctness in dress or scene does not necessarily give the illusion. Everything must be exaggerated in order that it may be visible across the footlights.

A deck that is too real may be off-putting. A card depicting an office-worker with a computer may be too “real” an image to correlate with someone’s job as carpenter or herbalist. An idealized movie star as Knight of Wands could do little to suggest a problematic boy friend. By contrast, a fantasy fairy tale. as in Pamela’s faux-medieval Minor Arcana, may be easier to inhabit. Moreover, it can help one see the mythic dimension of one’s own life.

The designer must insist on the balance being kept, and work in harmony with, and not be ruled by, the producer or stage manager. Of course the producer must have confidence in the designer to complete his work.

We may take this as a statement of the working relationship between Smith and Waite, in which Smith was cognizant of the importance of not being ruled by Waite, the stage manager/producer. Likewise, Waite apparently gave over illustration of the Minor Arcana cards primarily to Smith, with confidence in her ability to do justice to the task.

Regarding decks that are slavishly based on their predecessors, Pamela complains that all too often costumes are “hired merely in the tradition of the part, the model having done duty in many revivals.” So we should not be surprised when her deck takes a decidedly new form of expression. It might even make one wonder what Pamela would have thought of so many RWS influenced decks.

A great many people find her colors garish. When critiquing the artistic effect of her cards we should take into account that for Pamela:

Colours are forces but little understood. Strong colour is disliked, and perhaps the fear and hatred of strong, clean colour is due to ignorance.

She asks us to:

Observe the work of the French impressionist painters, who use red, blue and yellow side by side to get the effect of light and atmosphere. Is it the fear of the dreaded accusation of vulgarity? I believe the public would prefer the effect got by the use of strong primitive colour, if they saw it.

While some may see her strong colors as a call to vitality and a celebration of life like that perceived in the French theatre posters of the period, we see here that she was also influenced by the impressionist experiments in color theory.

How rarely does one see an entire production welded together into a thing of beauty by artist hands?

As we’ve already seen, historical correctness is secondary to an exaggerated illusion welded into “a comprehensive thing of beauty.” She further claims that costume is more important than scenery. The latter, she notes, should be kept simple and in harmony with the costumes. Nevertheless, Pamela ends her article with a plea for a dramatic library that would provide historical details for design purposes (much as can be found with simple google searches today). She asks, “Where would one look for the dress of a Jewish woman in England in the year 1185?” and answers herself, “There is the material to go on, given the knowledge of where to find it.” Here’s one source.

I read this as Pamela’s call for historical awareness at the same time that she observes the primacy of dedication to the art plus the necessity of illusion as essential to having one see with “a new pair of eyes and ears.” This is a formula with which all tarot readers have to contend. And then, knowing what we know of Pamela Colman Smith, we must add a significant dash of intuitive awareness allowing us to experience other realms of perception.

For the definitive book on her life and work, fully illustrated with never-before-seen art and photographs, please check out Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story (2018, USGames Systems, Inc.).

Please add your own thoughts in the comment section.

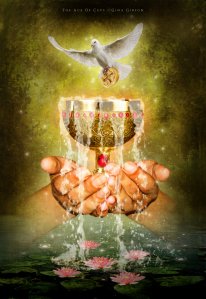

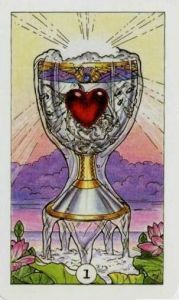

There is no single Jungian interpretation of the Ace of Cups. That it represents a major archetypal motif is without question for it suggests the feminine, mother, breast, womb, water, vessels, and related ideas of love, emotion, nourishment, healing, sacrifice, rebirth and renewal, the unconscious, imagination, empathy, psychic awareness and more. The value of a Jungian approach is that it encourages a Tarot reader to be aware of the multi-dimensional wealth of meaning in the cards, while allowing them to guide, honor and support a querent’s own wisdom and self-knowledge. You may want to read my other two posts on the Ace of Cups first. Part 1. Part 2.

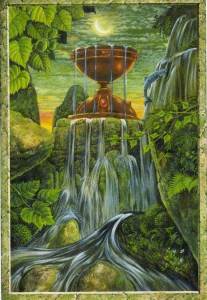

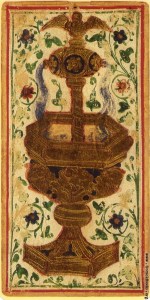

Druidcraft Tarot

First we have to ask: what is a Jungian approach to a symbol? Is it simply pointing out all the symbolic interpretations (see my earlier posts on the Ace of Cups) and mythological and cultural referents? From this point of view, I could begin with several quotes from Jung on the image of the cup and Grail:

The bowl is a vessel that receives or contains, and is therefore female. It is a symbol of the body which contains the anima, the breath and liquid of life. CW18. p 121.

Vessel symbolism probably contains a pagan relic which proved adaptable to Christianity, . . . which secured for the Christian Church [in Mary] the heritage of the Magna Mater, Isis, and other mother goddesses. CW6 ¶ 398.

The aesthetic form of the symbol must appeal so convincingly to our feelings that no argument can be raised against it. For a certain time the Grail symbol clearly fulfilled these requirements, and to this fact it owed its vitality. CW6 ¶ 401.

The symbolism of the vessel has pagan roots in the “magic cauldron” of Celtic mythology. Dagda, one of the benevolent gods of ancient Ireland, possesses such a cauldron, which supplies everybody with food according to his needs or merits. CW6 ¶ 401.

The Hermetic vessel, too, is a uterus of spiritual renewal or rebirth. This idea corresponds exactly to the text of the benedictio fontis [“blessed font”]. . . . We could take this water as the divine water of the [alchemical] art, since after the prima materia this is the real arcanum. . . . The water, or water of the Nile, had a special significance in ancient Egypt. . . A text from Edfu says: “I bring you the vessels . . . that you may drink of them; I refresh your heart that you may be satisfied.” CW13 ¶ 97.

“The healing cup is not unconnected with the “cup of salvation,” the Eucharistic Chalice, and with the vessel used in divination: This is the divining-vessel of Joseph and Anacreon. . . . The content is the water that Jesus changed into wine, and the water is also represented by the Jordan, which signifies the Logos, thus bringing out the analogy with the Chalice. Its content gives life and healing.” CW12 ¶ 551.

The water chalice is associated with the baptismal font, where the inner man is renewed as well as the body. This interpretation comes very close to the baptismal krater of Poimandres and to the Hermetic basin filled with nous [“mind, intellect”]. Here the water signifies the pneuma, i.e., the spirit of prophecy, and also the doctrine which a man receives and passes on to others.” CW11 ¶ 313,

Jung also writes of the alchemical water that “purifies everything and contains within itself everything (i.e., for the process of self-transformation)” – Jung’s parentheses. He continues with something apropos the dove on the Ace, “You must know that the art of alchemy is a gift of the Holy Spirit” CW18, p. 799.

We can see from these many references, and the ones in my other posts on the Ace of Cups, that this is an archetypal image: an archaic remnant of instinctual patterns of meaning in the human psyche that influences our psychology. Gathering all the mythic and artistic examples of the motif is called amplification.

Amplification is seeing what is behind an archetypal image or symbol, enlarging it so as to view it from different perspectives, restoring it to its original fullness to discover what kind of forces could be working in it.

However, is amplification the main or even true Jungian approach to Tarot? In fact, symbol amplification has a certain seductiveness in that we think that by gathering more and more examples of a motif, we’ll discover its true meaning.

Perhaps we need to start somewhere else. And this is what Jungian dream interpretation and active imagination does. My book, 21 Ways to Read a Tarot Card, details several Jungian-based tarot techniques, which are impossible to include in a single blog post.

When discussing dream interpretation we find Jung giving advice in what has become my favorite quote:

“I have always said to my pupils: ‘Learn as much as you can about symbolism; then forget it all when you are analyzing a dream’,” CW18, p. 418. [Or a tarot reading!]

Jung elaborates on this elsewhere:

“True art is creation, and creation is beyond all theories. That is why I say to any beginner: learn your theories as well as you can, but put them aside when you touch the miracle of the living soul. Not theories but your creative individuality alone must decide,” CW17 ¶ 313.

Morgan-Greer Tarot

This, to my mind, is the best advice for a Tarot reader. Learn as much as you can about Tarot and its history and symbolism, then forget it all when you are doing a reading. Actually, I would say, set it to one side in a space in your mind that will hold your associations ready as they are needed. Instead, embrace yourself as creative artist. Focus your attention and energies on touching “the miracle of the living soul” before you, which means using your intuition to guide querents into their own experience of the image, for only the person can ascertain the meaning(s) for themselves.

This brings us back to the Ace of Cups for it is up to the reader to become the container, the holder of energies for the associations and emotions of the querent. In a process similar to that in dream interpretation, I advocate being a mid-wife of the soul, assisting the querent to engage with the images on the card and bring their own wisdom to birth. I encourage personal associations that well-up from the unconscious while keeping them tethered to the cards in the spread. When tears or other subtle signs appear, know that emotions are activated that yield personal meaning.

Georgina Gibson Ace of Cups

As tarot reader, I am also like the dove, bearing the cards in my beak, touching on the unconscious waters of the living soul. The lotus blossoms below are rooted in the deep mud, rising through the waters to bloom in the light of consciousness. They are the realizations that a querent takes home from a Jungian approach to a reading. What blossoms is a result both of the querent’s own conscious realizations and the greater patterns that point to that person’s own myth.

For Jung, meaning is a meeting of the soul “on its own ground, whenever we are confronted with the real and crushing problems of life” CW17, ¶ 81. Meaning is found in the creative confrontation with the opposites and the synthesis of the self into the scheme of creation—their personal myth (paraphrase from Memories, Dreams, Reflections, p. 338). And, from The Myth of Meaning in the Work of C.G. Jung by Aniela Jaffé, we find that meaning is “a human interpretation or conjecture, a confession or a belief . . . created by consciousness, and its formulation is a myth” [no page number]. To summarize: meaning is a myth formulated by humans to answer the unanswerable. Jung frequently notes that meaning is present in an emotional response to an image.

“A great work of art [such as Tarot] is like a dream; for all its apparent obviousness it does not explain itself and is always ambiguous. . . . It [art/dream/tarot] presents an image in much the same way as nature allows a plant to grow, and it is up to us to draw conclusions. . . . To grasp its meaning, we must allow it to to shape us [to act upon us] as it shaped him [the artist]” Jung, Modern Man in Search of a Soul, p. 175.

Medieval Scapini Tarot

To do this, we may use word association, active imagination, dialog, and other interactive methods favored by Jungians. We may also want to be aware of the interplay of the parts of the psyche that have been activated or the stage of the alchemical process of individuation. However, in contrast to Jungian psychoanalysis, we keep the light of awareness focused on and through the querent’s cards and question, to what they most need to hear at this time.

To be clear, there are times when you’ll want to amplify the images on a card: to compare the mythical and symbolic elements with a client’s circumstances. And, in some cases it is helpful to present querents with the archetypal aspects of their pattern and where it is headed as foreshadowed in associated myths. As Jung explained:

“This comparative work gives us a most valuable insight into the structure of the unconscious. You have to hand the necessary parallels to the patients too, not of course in such an elaborate way as you would present it in a scientific study, but as much as each individual needs in order to understand his archetypal images. For he can see their real meaning only when they are not just a queer subjective experience with no external connections, but a typical, ever-recurring expression of the objective facts and processes of the human psyche. By objectifying his impersonal images, and understanding their inherent ideas, the patient is able to work out all the values of his archetypal material. Then he can really see it, and the unconscious becomes understandable to him. Moreover, this work has a definite effect upon him. Whatever he has put into it works back on him and produces a change of attitude. CW18 ¶ 401.

Given the Jungian approach, there is no way I can tell you what meaning the Ace of Cups will have for an individual, as even for the individual it will vary over time. So, coming back to where I started with Marie Louise von Franz, I want to amplify just one aspect of this Ace of Cups image that may, at some point elucidate the soul’s work in a person. In The Psychological Meaning of Redemption Motifs in Fairytales, Marie-Louise von Franz writes:

“The Benedictio Fontis, baptism in the Church, represents the cleansing of the human being and his transformation into a new spiritual being. . . . On the Saturday before Easter the baptismal water is always blessed . . . by [the priest’s] making the sign of the cross over it. . . . It is said that the Holy Ghost will impregnate the water . . . so that out of this uterus of the divine font a new creature may be born,” p. 35.

Although any water may be used there is a special water used for Roman Catholic baptism called Easter Water. Traditionally it is blessed on the last Saturday of Lent, Holy Saturday, in a ritual where the paschal or Easter candle [an Ace of Wands!], representing Christ risen from the dead, is held in the water and the Holy Spirit is called upon, saying, “Wherever we may be, make the Holy Spirit present to us who now implore Thy mercy.”

Von Franz explains:

“The light of the candle would represent the light of an understanding attitude, an enlightenment of the mind which now enters the unconscious and fertilizes it . . . handing back conscious understanding and truth to the unconscious from whence it came so that it may be increased in power and effect. There is also the union of the opposites—fire and water—and the result is a fiery water. The baptismal water of the Church is often called aqua ignita since it is said to contain the fire of the Holy Ghost,” p. 35-36.

Robin-Wood Tarot

So, while the querent may wax long and lovingly on their hopes for a new relationship or the beginnings of some work of the imagination, as a reader, I will be looking to the other cards in the spread to see where and how there may be an influx of grace in which the unconscious is ignited, impregnated and fertilized in preparation for a healing and spiritual renewal. Or, like mystic and Golden Dawn member, Evelyn Underhill, said of the related cup of the Eucharist, it bodes a Divine Presence and a movement toward Love.

Finally, in a Jungian approach to Tarot, a reader would be aware, when the Ace of Cups appears that, of Jung’s four functions, the Feeling Function is actively involved in the gestation of a new awareness. Among other possibilities, it may signal that the querent’s currently activated mode of consciousness centers around what feels pleasant or unpleasant to them, and so the reader might aid in making them more conscious of this.

A Jungian approach to Tarot requires quite a bit of reading and study, first to understand the Jungian “map of the psyche” (self, ego, anima/animus, shadow, etc.) and other concepts like individuation, the four functions and so on, and then to become familiar with the archetypes expressed through myth and symbol. However, it may be a relief to recognize that most people will find that a modern study of tarot will have already introduced them to many of the concepts and methods discovered and made popular by Jung.

______________________

I was initially inspired to write on the Ace of Cups in the Waite-Smith Tarot upon reading the Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz’ The Psychological Meaning of Redemption Motifs in Fairytales. Von Franz was also the co-author with Jung’s wife, Emma Jung, of The Grail Legend, which I studied a lifetime ago for my M.A. in English.

See also:

Part 1: Waite’s Eucharistic Ace of Cups.

Part 2: Ace of Cups Symbolism.

Carl Jung on the Major Arcana

Carl Jung and Tarot

Note: CW refers to the Collected Works of C.G. Jung. They are listed here. A bibliography of Jung’s publications is here. A good starting point for Tarot readers on Jung is Man and His Symbols (get an o.p. hardcover if you can). A list of great books by “Jungians” that are applicable to tarot is very, very long.

What happened to the Visconti Devil cards since they are missing from every 15th century Tarocchi deck?

As other cards are missing from these decks I never gave it much thought until Ria Dimitra, the author of the 2006 supernatural romance novel Visconti Devils, invited me to read her book. Her novel is an enjoyable, easy read about a modern Tarot artist who is intrigued by the mystery—why did none of the original, fifteenth century Renaissance Devil cards survive? There are no Tarot readings in her book, but the early history of the cards is well portrayed with no glaring errors, which is a remarkable feat in its own right.

Synchronistically, I had no sooner finished the book than I was perusing Andrea Vitali’s scholarly articles at LeTarot.it and read new evidence for the use, five centuries ago, of Tarot in witchcraft. I invite you to read what I wrote here about the 16th century Venetian witchcraft trials using the Devil card. Vitali’s article adds many interesting details (see first link at the end of this article).

It seems that when a lady wanted to satisfy a sinful lust or coerce an unresponsive gentleman, she knew it was inappropriate to appeal to Heaven and so she would make her appeal to the Devil, sometimes in the church itself. In a reversal of the regular prayers, the woman would place the Devil from the Tarot pack on a shelf “ass up,” with a lighted oil lamp having a wick from the bell cord of a church held upside down. Hands were to be clasp together behind the back making the “fig” gesture. With hair down, she would recite the “Our Father” for three consecutive nights. Sometimes blood and bones would be included and both hanged and ‘quartered’ men were called on.

When caught, the punishments were relatively mild considering that these women could have been killed for their actions. Instead, their superstitious rites were seen more as a feminine weakness brought about through the sin of lust. One woman, Catena, was, among other indignities, publicly pilloried with a miter on her head (see the miter used as an indication of heresy in the picture on right). The miter was inscribed with a sign saying she was condemned as a witch (striga) for the magical use of herbs (herbera). This ironic use of the miter, usually worn by both bishops and pope, is reminiscent of the late 15th century Sermones de Ludo Cum Aliis (“Steele Manuscript”) in which La Papessa in the Tarot is described as “O miseri quod negat Christiana fides”: “O miserable ones, what [with respect to which] the Christian faith denies” (or, as several online translators offer, “O wretched that denies the Christian faith”).”

But, as to our opening question, there is no way we can know for sure what happened to the earliest Devil cards (if they even existed). However, it is interesting to speculate based on likely scenarios.

According to Vitali’s research it seems that Emilia “took a tarot card, and it was the devil, that she stole for the purpose.” It appears it may have been a requirement of this magic rite that the Devil card had to be stolen. Could this be why the Devil card and, perhaps a few of the other cards, are missing from all the earliest Tarot decks?

The use of images for invocation was common at this time, based on the belief that the image stood as a surrogate for the being depicted—that there was a direct physical connection between the image and its referent. Furthermore, early woodcut Tarot cards were produced in the same print shops as saints cards and may even, on occasion, have been substituted for each other.

Girolamo Menghi in Flagellum daemonum (1577) recommended the physical and verbal abuse of images of the devil as an operative way of impacting evil spirits. Subsequent guides to exorcism followed Menghi’s lead, calling for the exorcist to draw or paint the devil’s portrait, along with his name, and then burn the paper. Such “exorcism by fire” evolved into the bonfires of vanities, especially at what was deemed the devil’s feast of Carnival. Fredrika H. Jacobs in Votive Panels and Popular Piety in Early Modern Italy further explains, “It was believed that the pain inflicted on the image was transferred to and experienced by the devil.”

Similarly, as we’ve seen from the court records in Venice, the devil could be invoked to grant wishes that were unworthy to be asked of the holy family or the saints. Invocations of entities through images by persons or in situations other than those ordained by the Church was regarded as superstition, witchcraft or heresy.

In the Visconti-Sforza (Pierpont-Morgan/Brera) deck only four cards are missing: The Devil, The Tower, Three of Swords and Knight of Coins. It’s easy to imagine a ritual invoking the Devil to punish the Knight of Coins with the desctructive Tower because of a betrayal or heartbreak depicted by the Three of Swords (see the Sola Busca deck on right).

What do you think?

For further details read:

“Tarot and Inquisitors: In the Serenissima and Trentino, between ‘witches’ and ‘Diabolical Priests'” by Andrea Vitali, translated from the Italian by Michael S. Howard.

“The Conjuration of the Tarrocco: A magic ritual in sixteenth-century Venice” by Andrea Vitali, translated from the Italian by Michael S. Howard.

“Tarot and Playing Cards in Witchcraft” by Mary K. Greer.

Votive Panels and Popular Piety in Early Modern Italy by Fredrika H. Jacobs.

Also read the following discussion of early evidence of divination with Tarot including ruminations on the subject by the translator Michael Howard:

“Il Torracchione Desolato: A card-reading sorceress in a poem of the XVIIth century” by Andrea Vitali, translated from the Italian by Michael S. Howard.

I highly recommend the numerous translations and articles by Michael S. Howard on historical Tarot. A directory to where they can be found is at: http://michaelshoward.blogspot.com. I am so grateful to him for all he has done to make Italian, French and out-of-print sources available to us all.

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Mary K. Greer has made tarot her life work. Check here for reports of goings-on in the world of tarot and cartomancy, articles on the history and practice of tarot, and materials on other cartomancy decks. Sorry, I no longer write reviews. Contact me

Recent Comments